In the shadow of China’s towering automotive achievements lies a complex tale of innovation, ambition, and market forces run amok.

From the historic rollout of the first ‘Liberation’ truck in 1956 to the present, where Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) dominate the global stage, the journey has been nothing short of remarkable. Yet, this success story is tinged with all sorts of challenges.

With President Trump returning to the White House, the term ‘tariff’, which he famously lauded as “the most beautiful word,” is once again taking centre stage in matters of global trade and politics. Earlier this year, President Trump announced a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico, as well as an additional 20% tariff on Chinese imports, citing the countries’ inadequate actions to curb fentanyl flows.

Then, as part of President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ announcement on 2 April 2025, he imposed an additional 34% tariff on Chinese imports, with the new tariff going into effect on 9 April 2025. As a result, Chinese EV makers, who have experienced a surge in exports in recent years, are subject to a whopping total of 154% tariff.

Despite the dual challenges of internal economic strains and rising trade obstacles, Chinese automakers are actively transforming the global automotive landscape. This period of change not only spotlights the companies but also prompts a deeper examination of the sustainability and competitiveness of their rapid growth, as well as the broader implications for the future of transportation.

A sudden success

China’s automotive odyssey commenced in 1956 with the first ‘Liberation’ brand truck coming off the production line at the First Automobile Works in Changchun, Jilin Province.1 This pivotal moment signified the close of a chapter in which China lacked the capability to produce its own automobiles.

However, it was not until Deng Xiaoping’s open-door policy in the late 1970s that the industry’s engine truly started. Foreign joint ventures injected much-needed technology and expertise into China’s auto industry, steering it onto the fast track.

The subsequent decades marked a period of explosive growth. Admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001 kick-started an era of unparalleled expansion, with the country’s economic rise fueling a burgeoning demand for passenger cars. This shift culminated in 2009 as China dethroned the US as the world’s top auto market, a position it has not relinquished since.

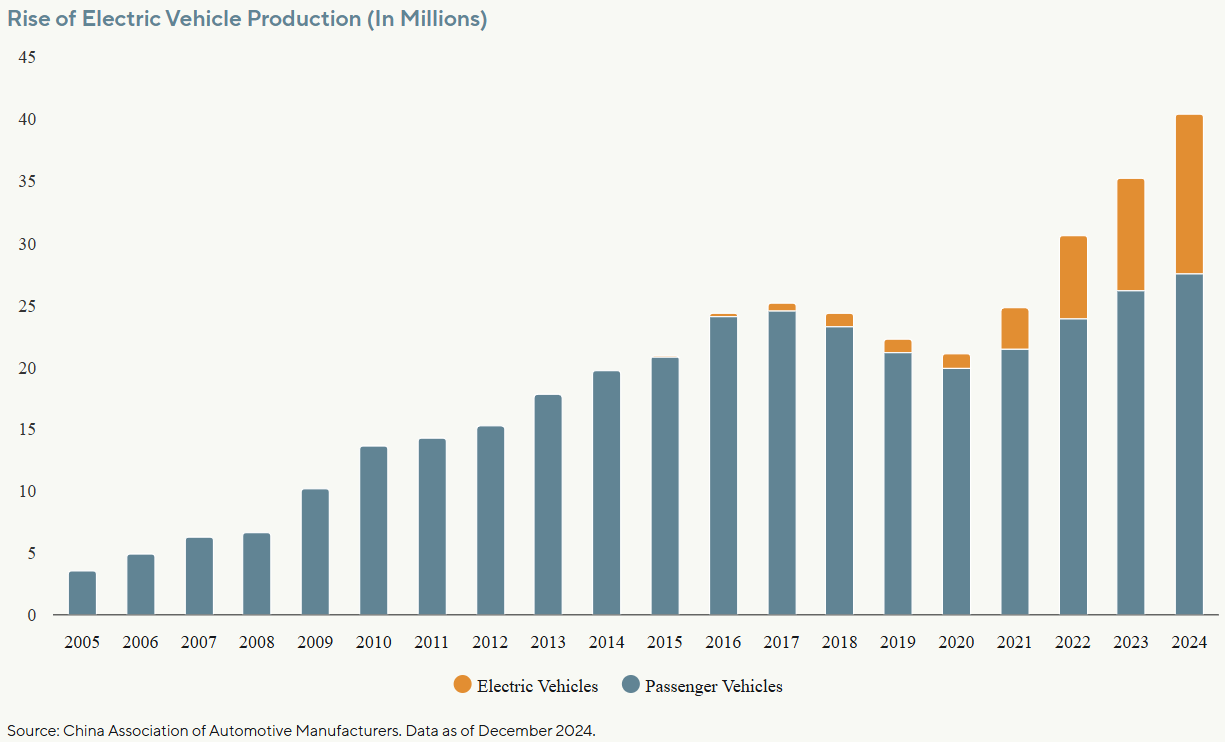

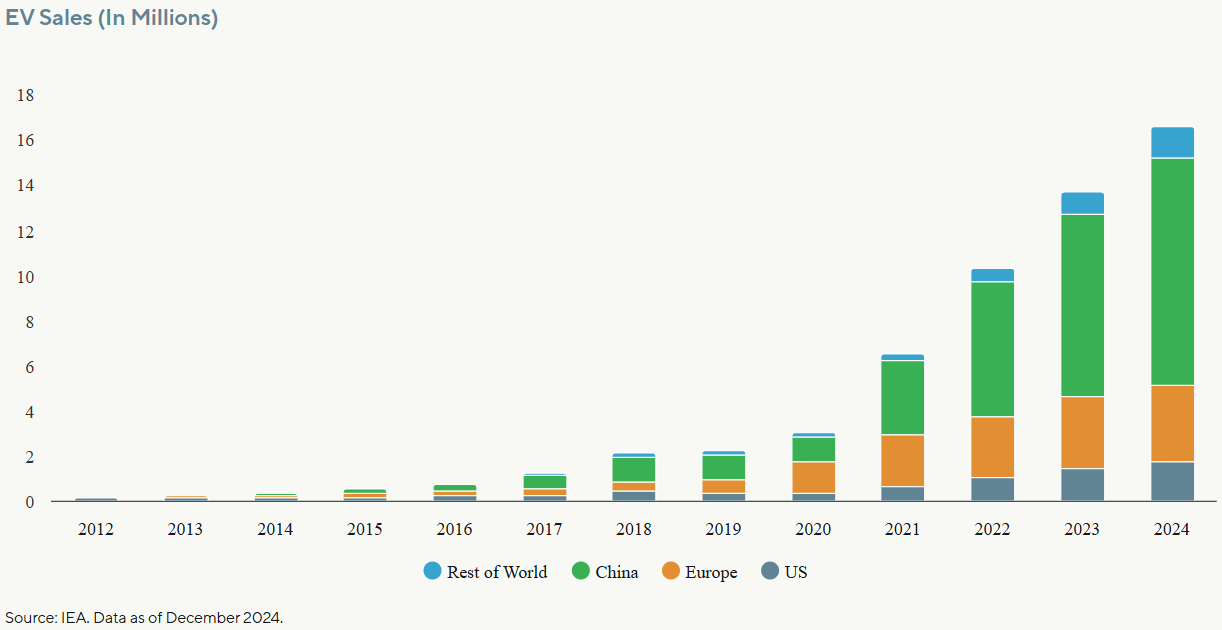

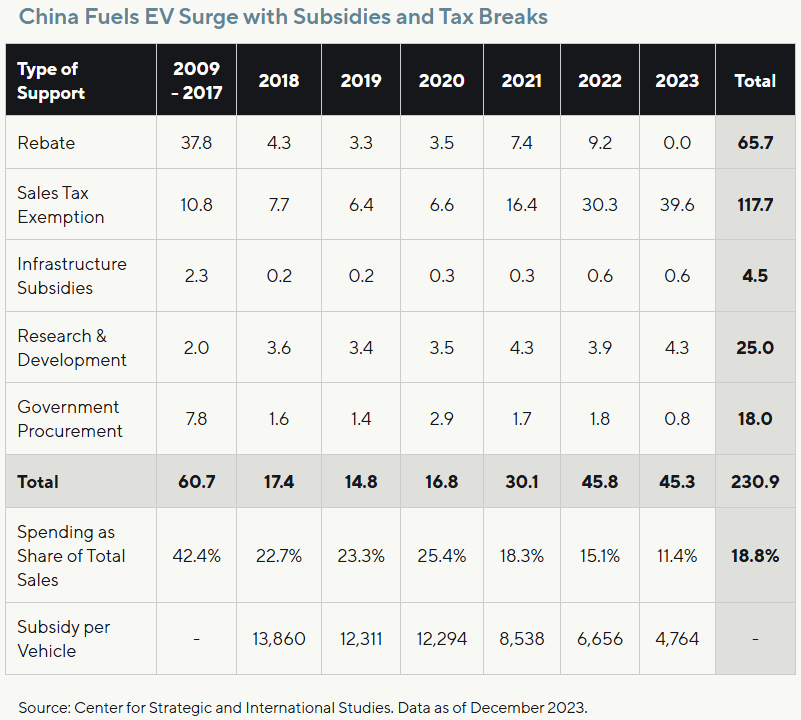

The surge in vehicle production and sales has contributed to urban pollution and traffic congestion in China, prompting Beijing to steer toward electric vehicles as a remedy in recent years. Backed by government support and their robust manufacturing capabilities, Chinese automakers shot to dominate the global EV market, claiming about 70% of total new registrations last year.2

An inevitable glut

However, the sector has become overcrowded quickly. At present, there are over 60 passenger car manufacturers in China, far exceeding the 20 to 30 companies typically found in other more established markets. The oversupply in EVs is further exacerbated by government incentives and access to cheap financing. By the end of 2023, Chinese EV capacity had surpassed what was needed to meet global demand, reaching a level equivalent to 116% of worldwide needs, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis.3

The excess capacity reflects China’s distinct market dynamics. Unlike the cyclical fluctuations seen in other markets, demand in China often starts from an extremely low baseline and then expands dramatically in both scale and speed. This pattern poses challenges for accurately forecasting market size, particularly at the onset of a growth cycle.

On the participants’ side, certain companies have managed to ride the wave of transient undersupply, reaping significant profits and capturing the attention of capital markets. This profitability often sparks a frenzied reaction from market followers, eager to invest in the burgeoning sector. When this unpredictable demand surge is met with a swift supply-side reaction, the likelihood of imbalances naturally increases.

Government policies, while aimed at promoting industry development, can exacerbate such imbalances. In January 2024, the Chinese government updated its EV objectives, mandating that EVs represent 45% of all new car sales by 2027.4 Although national EV purchase incentives were phased out in 2023, local subsidies remain, fostering sector expansion. Additionally, China’s “dual-credit system” has simplified the process for consumers to acquire license plates for EVs, further bolstering the industry.

In our view, the industry mirrors the initial success of China’s solar and steel sectors. But the long-term effects are questionable, as this pattern of state-driven growth could lead to a repeat of past challenges. In those industries, subsidies triggered rapid expansion and market dominance, only for overcapacity to flood the market, driving down prices and profitability as global demand lagged.5 Without sustained innovation or strong export markets, the industry may face a familiar downfall: a policy-fueled boom giving way to a bust as subsidies fade and excess supply overwhelms weaker firms.

Tesla, Inc. experienced these dynamics firsthand. The American automaker was able to construct a gigafactory in Shanghai within a year. To finance the plant, Tesla received US$521 million in loans from Chinese banks at favorable interest rates, and US$82 million in grant funding. The local Shanghai government also granted Tesla a corporate income tax rate of 15% for 2019 through 2023, compared to the typical 25% rate in China.6

On the other hand, the completion of Tesla’s manufacturing facility in Berlin took about two years. Productions at the factory have faced numerous delays due to concerns about its environmental impact, as well as Red Sea shipping attacks. During a 2023 visit to the Shanghai gigafactory, Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk praised the facility, stating, “I tell people throughout the world, the cars we produce here are not just the most efficient production, but also the highest quality.”7

For now, the surplus seems unabated, with most managements across the Chinese auto industry still maintaining a positive outlook. According to Goldman Sachs, companies were expected to expand their EV capacity by 18% in 2024 to 17 million units—three million more than what the world needs.3

Cost control created cost advantages

Chinese EV manufacturers set themselves apart from the competition mainly through their cost controlling measures. A study by Goldman Sachs showed that Chinese automakers’ costs are 47% lower than those of their global peers.3 Economies of scale are crucial in the capital-intensive sector, with high production facility utilization rates being crucial for spreading out fixed costs and optimizing variable cost management.

BYD Company Ltd., a leading EV player in China, has harnessed vertical integration as a strategic lever to achieve a significant cost controlling advantage. By managing the entire production chain, from securing raw materials to manufacturing core components like batteries and electronic control systems in-house, BYD effectively reduces reliance on external suppliers, minimizes production costs, and mitigates supply chain risks.

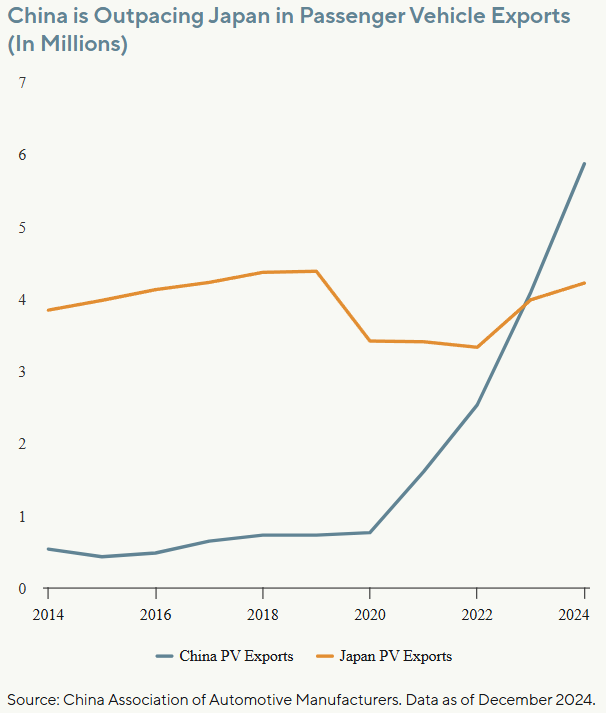

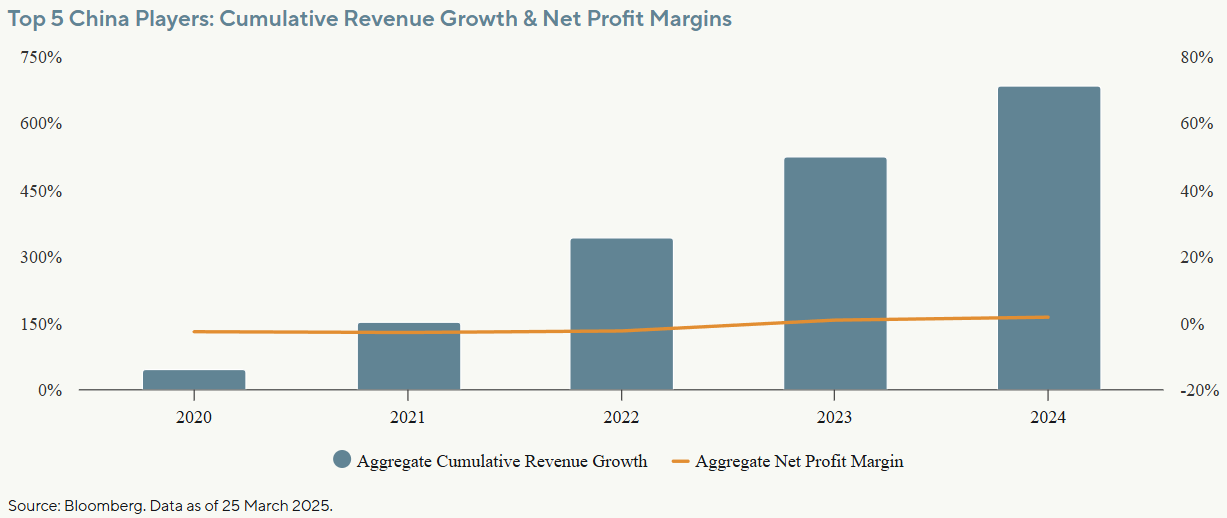

Within China, growing popularity of EVs took a toll on the country’s conventional internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, whose sales contracted by 17.4% in 2024.8 Overall, its automotive market is experiencing saturation, evidenced by a capacity utilization drop to 56% in 2024. This saturation is driving Chinese automakers to pursue international markets. From 2020 to 2024, China’s auto exports surged by nearly 500%, as reported by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. In 2024, China exported a historic 5.86 million vehicles, including 1.3 million EVs, surpassing Japan as the world’s leading car exporter.8

Thin margins among Chinese EV producers have become a growing concern as fierce competition and overcapacity take their toll. Companies like BYD, Xpeng, and Li Auto are locked in a price war to capture market share, driving down vehicle prices while production costs remain high due to reliance on expensive batteries and advanced tech.9 Government subsidies have softened the blow for some, but as these incentives taper off and domestic demand slows, many firms are struggling to turn a profit. This race to the bottom threatens the sustainability of the industry over the long run.

Global tensions

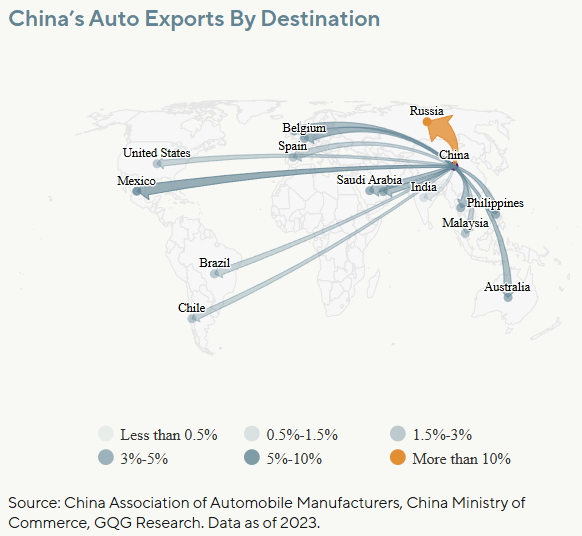

However, the surging export activity of Chinese automakers has triggered a global response. Critics argue that Chinese cars, often coming with deflated price tags, have undercut producers abroad and sparked a price war that few can sustain. Nations, feeling the pinch of cheap imports, resort to protective tariffs and other barriers in a bid to shield their industries, sometimes igniting trade disputes with Beijing.

In the US, the Biden administration doubled tariffs on EV imports from China to 100% beginning in August 2024, posing significant challenges for Chinese firms targeting the American market. Europe, while showing a divided stance, voted in October 2024 to impose tariffs up to 45% on Chinese automakers, while over 40% of China’s EV exports are absorbed by this crucial market.10

Contrastingly, Brazil’s rising demand for Chinese EVs has led to gradual tariff increases and local manufacturing by companies like BYD, as Mexico also sees Chinese firms establishing production to circumvent US tariffs and serve the North American region, with Thailand in Asia-Pacific rolling out incentives for zero-emission vehicles, attracting Chinese EV manufacturers.

China’s auto exports by destination

The trend of establishing overseas production facilities is not without its financial challenges, as the costs associated with setting up factories and navigating different regulatory environments may weigh on the profits of Chinese EV makers.

“In theory, there’s nothing wrong [with affordable Chinese EVs outside of China], but in practice, there’s a lot wrong,” former US ambassador to China Nicholas Burns said in an interview last year. “The government of China and the provincial governments are subsidizing the Chinese EV manufacturers so there’s no level playing field, and they take the cars, they sell them below the cost of production into Europe or Brazil or the US.”11

Hidden challenges come to light

But the issue isn’t merely external. Overcapacity signifies a deeper inefficiency within China’s own resource allocation and its industrial sectors. EV overproduction squanders raw materials, energy, and labor, while intensifying environmental woes. Over the long run, the misallocation of capital may hamper China’s long-term growth prospects by diverting resources from potentially more productive sectors. For Chinese companies, the burden of excess capacity also increases financial stress, with potential loan defaults posing a threat to the stability of China’s banking system.

For example, as Nio Inc., a Chinese EV maker, was on the brink of exhausting its funds in 2020, a provincial government swiftly stepped in with a $1 billion investment for a 24% stake in the company. Concurrently, a state-controlled bank led a group of other lenders and pumped in another $1.6 billion. These state investors are probably facing buyer’s remorse now, as Nio’s share price had tumbled as much as 90% from its highs.12

Environmental issues remain, even with zero-emission commitments. As China’s leading EV manufacturer, BYD has made significant strides in advancing sustainability, staying in line with Beijing’s strategic ambitions to cap carbon emissions. However, in 2023, BYD found itself embroiled in controversy with competitor Great Wall Motors.

Great Wall alleged to three regulatory bodies that BYD’s hybrid models were equipped with atmospheric pressure fuel tanks instead of the required high-pressure ones, potentially causing non-compliance with emission standards and gaining a cost advantage by simplifying vehicle configurations.

In a hastily composed response, BYD vehemently rebutted the accusations but failed to address the heart of Great Wall Motors’ core claims. Instead, BYD challenged the completeness of the emissions test report and shifted the discussion toward themes of national interest, focusing on the “new energy business” and the promotion of “Chinese brands.”13

Still, it remains to be seen whether BYD has indeed skirted regulations.

China’s pole position in the global automotive race

In the global automotive race, China’s position is both enviable and precarious. Following a period of rapid growth, Chinese automakers, especially those emerging in the EV sector, are now grappling with an economic slowdown domestically and starting to dump low-priced cars overseas. This has led to a significant market imbalance with the potential to unleash a series of aftershocks.

The state of China’s auto industry acts as a pulse-check for the vitality of the world’s second-largest economy, with its trends being closely monitored as an indicator of either burgeoning prosperity or looming challenges.

At GQG, we closely track these industrial and geopolitical developments, integrating them into our in-depth company research. Our investment decisions are made within a multifaceted, complex global context.

We believe China’s automotive sector stands as a critical indictor of the economic strategies that will shape President Trump’s second term in office. President Trump’s emphasis on encouraging domestic manufacturing foreshadowed his latest move to increase the 100% tariffs imposed by the Biden administration on Chinese-made EVs. Concurrently, President Trump’s tight-knit relationship with Tesla’s Elon Musk, whose company has considerable investments in China, is likely to introduce a layer of intricacy to the development of these trade policies.

Stay buckled up.

Carolyn Cui is a senior investment analyst at GQG Partners. This article contains general information only, does not contain any personal advice and does not consider any prospective investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making any investment decision, you should seek expert, professional advice.

End notes

1“The First Liberation Brand Truck.” People’s Daily Online.

2“China’s EV Sales Account for 70% of Global Total.” Sina Finance.

3Dmitrieva, Katia. “Goldman Sees China Oversupply Easing – Just Not for EVs.” Bloomberg. August 7, 2024.

4Xiao, Zhang. “The Central Committee of the Communist Part of China and the State Counsil: By 2027, the proportion of new energy vehicles in new vehicles will strive to reach 45%.” CBN.

5”China in Transition: China’s capacity – the imbalance, the inflections, and beyond cycles”. Goldman Sachs Equity Research. August 6, 2024.

6Armental, Maria. “Tesla Reaches Deal With Lenders in China.” Wall Street Journal. March 11, 2019.

7He, Laura. “Elon Musk says his Shanghai factory makes the ‘highest quality’ Teslas.” CNN Business. June 2, 2023.

7Ziye, Wu. “China’s Automobile Exports Reach New Heights Again; Which Markets Are More Popular?” January 24, 2025.

9China Passenger Car Association. December 20, 2024.

10Eddy, Melissa and Jenny Gross. “Europe Imposes Higher Tariffs on Electric Vehicles Made in China.” The New York Times. October 30, 2024.

11Pak, Jennifer. “How can China make EVs that sell for less than $20,000?” Marketplace. September 9, 2024.

12Fang, Alex and Yifan Yu. “China Startup NIO gains $1bn state funding to chase Tesla.” Nikkei Asia. April 30, 2020.

13Goh, Brenda, Yan Zhang, and Oiaoyi Li. “Great Wall Motor says rival BYD failing on hybrid emissions.” Reuters. May 25, 2023.