“Women invest less aggressively than men.”

How many times have you heard that assertion? And indeed, numerous studies point to women having lower stock weightings than men.

But a closer look at the data suggest that women’s lower average incomes - rather than gender-related risk preferences - are the key driver behind their lower average allocations to stocks. Women earn less, on average, than men. And not surprisingly, people with lower incomes contribute less and invest less in stocks than do higher-income people.

That skews the data on women’s average savings rates and equity allocations downward. But after controlling for income, it appears that women contribute as much to their retirement accounts and invest just as much in stocks as men at the same income levels.

That suggests that the key area of concern for women’s financial health relates to income rather than any sort of risk aversion that’s specific to women.

Digging into the data

To be sure, it can be difficult to draw conclusions about how people invest, or how much. There’s no central repository of information about investing behaviors for women or men. Any hard data is siloed by investment provider and account type. To the extent that investment firms study and share information about their investors’ choices, it’s necessarily influenced by the specific composition of their client bases: income levels, what industries their clients work in, and so forth.

The data from individual firms may not be representative of the investing population at large. Extrapolating conclusions from brokerage accounts - rather than retirement accounts where it’s at least likely that most contributors are saving toward retirement rather than shorter-term goals - seems especially risky.

Moreover, numerous factors may influence investment decisions: income, education level, marital status, age, and gender, to name some of the key ones. That makes it difficult to untangle what role gender plays in investment decision-making.

(Note that some of the following data relates to the US data, although the conclusions have general applicability. A section at the end is added on Australian data).

To help shed some light on these issues, I delved into available research to look at women’s investing behaviors in three key areas: contribution rates, equity weightings, and willingness to use professional advice. I focused on retirement-plan participants in an effort to remove the noise of people saving for goals other than retirement.

The conclusion? Women do indeed appear to exhibit different behaviors than men in each of the three areas. But many of those trends decline or melt away altogether when the data are adjusted for demographics, especially income level.

Participation/savings rates

Women have fewer financial assets and lower company retirement plan balances, on average, than their male counterparts.

In Vanguard’s 2020 How America Saves report, a compendium of statistics on more than 5 million participants in Vanguard 401(k) plans (roughly equivalent to Australia's superannuation system), the average deferral rate (that is, the portion of wages automatically deducted for retirement savings) for men was estimated to be 7.1% in 2019, versus 6.7% for women. Interestingly, the gap in deferral rates has widened between genders over the past decade. The average deferral rate for both men and women in Vanguard retirement plans in 2010 was 6.9%.

(Note the article on How Australia Saves here).

David Blanchett, Head of Retirement Research for Morningstar Investment Management, made a similar observation when assessing the behavior of more than 1 million retirement savings participants, using data from another major retirement-plan recordkeeper. The average deferral rate was 9% for male participants in that sample group, versus 8.1% for women.

Yet intuitively, those differences appear to be related to income levels. In the Vanguard research, for example, women with incomes of less than $29,999 had lower deferral rates than males at that same income level. But at every income band over $30,000, women actually invested more than males at that same income threshold. For example, women with incomes between $75,000 and $99,999 deferred 8.3% of their salaries, versus 7.8% for men at that same income level. Blanchett’s observation was similar: After controlling for demographics, the differential in contribution rates between men and women was just 0.01%.

Men were more likely to contribute the maximum allowable amount to their company retirement plans, according to Vanguard’s report. 11% of male company retirement plan participants did so, as of 2019, versus just 8% for women. But here again, that differential likely owes to income differences: Because of men’s higher average salaries, they likely have greater wherewithal to contribute the maximum allowable amount.

Investing choices/asset allocation

What do the data say about investment choices - specifically, the oft-cited assertion that women are more conservative than men? The available research suggests that the answer here, too, is nuanced.

Women allocated their pensions more conservatively than men, according to a 1996 study by Vickie L. Bajtelsmit and Jack L. VanDerHei. After examining investment choices for 20,000 management employees at a large US employer, the researchers found that women were more likely to invest in fixed-income investments than their male counterparts and less likely to invest in employer stock. At the same time, the study’s authors pointed out that they were missing information on the household’s wealth and marital status, which could be contributing factors to the participant’s allocation choices.

A 2008 study by Ann Marie Hibbert, Edward Lawrence, and Arun Prakash found that single men and single women with the same educational attainment (at least a graduate-level degree) tended to invest similarly; single women included in the survey were no more risk-averse than single men.

In the data set he examined, Blanchett looked at company retirement plan participants who were self-directing their own accounts, in an effort to remove the target-date effect and home in specifically on how men and women allocated their assets. Blanchett did observe a differential: The average equity allocation for self-directed female participants was 72%, versus 76% for men. However, after controlling for demographics, including income, the gap shrunk to less than 2 percentage points.

Additional comment based on Australian data

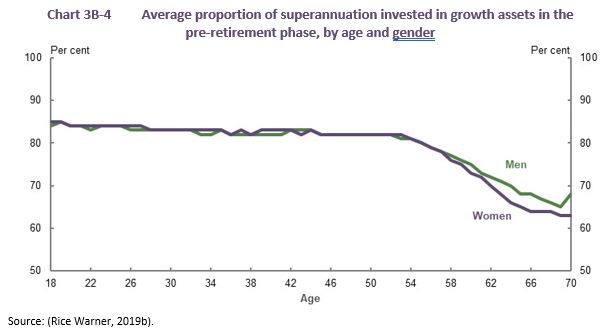

Rice Warner presented the recent Retirement Income Review with a table, shown below, showing men and women have similar proportions of superannuation invested in growth assets during the pre-retirement phase, as expected in a system with strong defaults. However, a gap opens from age 60 onwards. Rice Warner also quoted the US Vanguard numbers.

Willingness to ask for advice

What about the likelihood that women will rely on professional investment advice relative to men?

Women were more likely to rely on a professionally managed solution for their investments, according to Vanguard’s report. 40% of female-owned accounts in Vanguard’s survey included a target-date fund in 2019 versus just 35% for male-owned accounts.

Blanchett found a similar pattern in the data set he examined: 34% of women retirement plan participants went the self-directed route (that is, eschewed target-date and managed account offerings), versus 41% of men. But he notes that higher-income participants are generally more likely to self-direct their allocations. That means that the differential in advice-seeking by gender was minor overall. Adjusted for income and other factors, women were still more likely to rely on professional management then men, but the difference was fewer than 3 percentage points.

Conclusions

Addressing income differences, and in turn savings rates, especially at lower income levels, is key to healing the gender gap with net worth and retirement savings. Of course, that’s easier said than done. A complex set of factors contribute to the lifetime income gap between men and women - notably, the fact that women are much more likely to serve as caregivers for children or elderly parents than are men.

The research suggests that financial advisors shouldn’t assume that their female clients are more risk-averse than their male clients. A 2005 study suggested that financial advisors often did just that, even for male and female clients with the same levels of wealth.

Footnote to Australian version

The Retirement Income Review devotes a section on pages 257 to 283 to 'Gender gaps in retirement incomes'. Many of the conclusions are similar to the US experience. Specifically, it identifies that the gender earnings gap during a working life has a significant bearing on the superannuation imbalances at retirement. The earnings gap is caused by:

- Work in lower paid roles

- Work in lower paid industries

- Work part-time or casually

- Take career breaks from paid employment to care for others, including raising children

- Experience discrimination and harassment in the workforce

- Experience family and domestic violence

The Review noted:

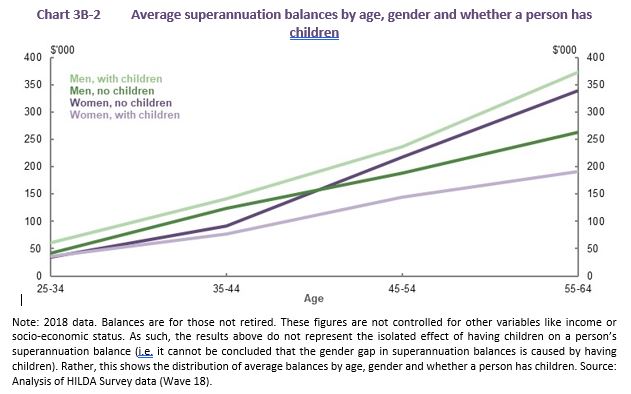

"The average superannuation balances of men and women without children are broadly similar until ages 45-54. Lower labour force participation and earnings — taking career breaks and working part-time to care for children — contribute to women with children having lower superannuation balances than women without children."

The following chart from the Review shows significantly higher super balances for women with no children. It also raises a policy issue on the extent to which superannuation should be judged according to the assets of a couple.

Christine Benz is Morningstar’s Director of Personal Finance. Any Morningstar recommendations contained in this report are based on the full research report available from Morningstar.

This article does not consider the circumstances of any investor, and editing and additions have been made to the original US version for an Australian audience.

Try Morningstar Premium for free