The intergenerational transfer of wealth in this country is picking up pace. COVID has seen many older people reassess what they want going forward, a big part of which is determining how to provide for the next generation.

Put simply, we’re at the end of the Boomer phase and the beginning of the Millennial/Gen Z phase. The wealth management industry will deal with the Boomers retiring, the transition of Gen X to being the elders of the workforce, and the rise of the Millennials/Gen Z. The way it will do this is to change its products and services, and in today’s digitised world that means primarily through changes in technology.

The generations

While marketers, media and politicians love to talk about ‘Baby Boomers’ and ‘Millennials’ using arbitrary windows of time, it is important to remember that lives are bigger than categories and we can be prone to over generalisation.

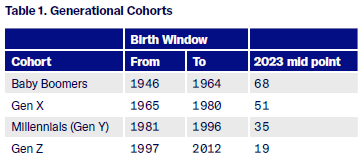

That said, ‘generations’ are a useful tool for analysis. This paper uses the definition provided by Australian Bureau of Statistics shown in table 1.

Source: ABS

The defining characteristic of the table is the commencement of the reconstruction era that started in 1946 after the end of World War 2. From that point, the Boomer generation is generally accepted to be a 20-year generational period, and then each generation is a subsequent 15-year generational period.

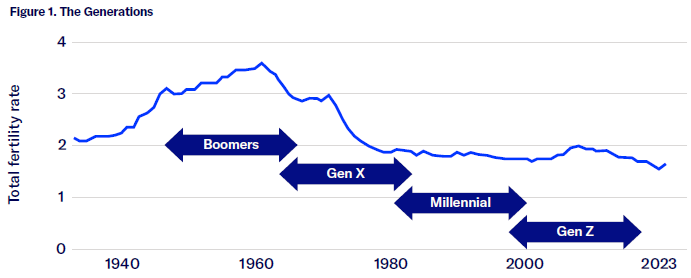

The best way to understand why the Baby Boomer generation has been so consequential is to look at the total fertility rate in Table 1.

The over-representation of one demographic cohort has been characterised as a “bubble” in the population numbers, which is why the “Baby Boomer bubble” has been a constant fixture in discussions about generations and their needs and wants. It’s fair to say that the Baby Boomer bubble has been the defining force that has cleared all before it, and its members have also collected resources and wealth as the systems changed to accommodate them and their looming retirement and aged care. And for good reason too, as up until now the Baby Boomers have been the largest and most consequential demographic cohort in Australia since the post war era started.

The boom required more resources such as larger houses, schools, hospitals and cars, the economy expanded rapidly as it consumed to catch up to the needs of the new generation, and the infrastructure of the country grew to support it. Then as the Boomers grew up, they needed education resulting in an expansion of the university system. As they then moved into work, the workplace had to accommodate a workforce that was not just larger from population growth but was also larger because the post war era embraced feminism and women’s rights meaning that women were also available for work.

At this point we can also add to this population boom and economic growth the fact that improvements in the areas of general healthcare and medical technology also meant that life expectancy was also increasing, and so governments became aware of the growing need to plan for the fact that pension and aged care systems were going to have to digest age care demands that were simultaneously going to be more expensive and over longer time frames than what the previous pension system was designed to support. This meant saving for retirement needed to be a priority which gave rise to the “Superannuation System” that has become the bedrock of financial services in Australia today.

Source: ABS

On the cusp of intergenerational change

The Baby Boomer bubble is starting to deflate before our very eyes.

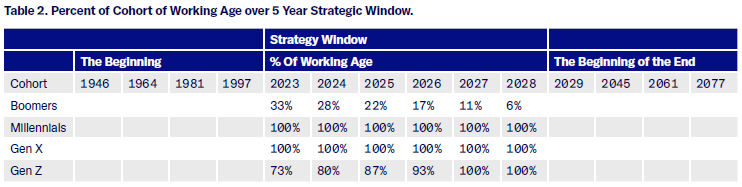

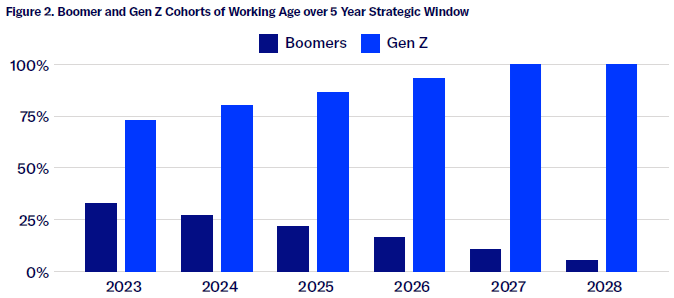

Table 2 shows the percentage of each cohort that will be of working age during our 5 years planning horizon and Figure 2 shows the same data for only the Gen Z and Boomer cohort.

Within 5 years, all Baby Boomers will be eligible for retirement and the Baby Boomer bubble will have all but deflated out of the workforce by 2028. And it doesn’t stop there.

In 2029 the first of the Baby Boomers will reach their statistical age of death (Men 81, Women 85) which means that the Baby Boomer bubble will start to deflate completely.

The impact of this on the wealth management industry is three-fold:

- Baby Boomer superannuation balances will start to deflate out of the superannuation system through retirement consumption, followed by disbursement through the inheritance process.

- Gen X are now the group preparing for retirement and they will become the large balance superannuation account holders.

- With Gen Z fully deployed into the workforce, the predominant demographic groups needing to be serviced by the industry will be Millennials/Gen Z.

Source: ABS

Source: AIHW

Financial flow changes

The exit of the Boomers from the workforce means that for the first time in its history, the retirement system is going to see retirement phase withdrawals from its largest accounts, as those in the 60-64 age group have an average balance of $323,000 compared to the younger generations where those in the 30-34 age group have an average balance of $45,000.

While it is difficult to predict the future and how the money will flow from where, to whom, and where it will end up, we can make inferences based on what we see in the superannuation balance and housing data that we know today. If we start with superannuation balances, we find that the facts don’t really match the prevailing narrative, that super is an inheritance tax planning device.

Research from The Association of Superannuation Funds in Australian (ASFA) shows that while it is true that there are some large accounts, Australian Tax Office (ATO) data in 2018-19 showed that there were only 322,200 accounts with balances above $1 million. This number will have increased given investment returns since that time, however the system favoured the older participants as they had the benefit of a period when contribution limits were not as restrictive as they are for today’s participants, and so the younger generations are less likely to be able to accumulate such large balances, in inflation adjusted terms. Regardless, these accounts are outliers that can be ignored when looking at the mechanics of the system given that the total number of superannuation accounts is 23.3 million.

If we look at the ASFA data on the group that will retire and leave the system over the next 20 years, the average balance across genders for those in the 60-75-year-old group is just under $400,000, however it is highly skewed by the larger balances. If we look at the median, the balance across genders in this group is approximately $180,000, which means that 50% of account holders in this age group have $180,000 or less in their retirement savings accounts. In other words, the larger share of the flow of money will be completely out of the system. This also corresponds with research from ASFA which shows that 80% of those who died over 60, and 90% of those over 80, had no super at death.

The question arises as to where this money will flow? If we look at Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) research into home ownership across the generations, we see that only 19.4% of Baby Boomers own their home outright, with 46.4% still having a mortgage, and 30.2% renting. While the value of their properties will have increased in capital value, it is not a stretch to assume that retirement funds will be used to pay down mortgages, especially if a large cash balance reduces access to pension entitlements.

Another tailwind behind the money leaving the system is the increasing cost of living and the impacts of high inflation as the global economy transitions through a regime change, away from cheap money and low inflation to higher interest rates and high inflation. Recent ASFA research shows inflation added 9% for singles and 7.8% for couples to the balance needed to have a comfortable retirement. The balances required to have a comfortable retirement are an estimated $690,000 for couples and $595,000 for singles. These numbers will compound again in 2024 as we already know that inflation is still high. An uncomfortable reminder about the thief that is inflation is that these numbers assume an annual investment return of 6%. This means that in the current environment of high inflation, retirement accounts are going backwards in real terms. At this time, you have to save more to stand still, while you are also living in the present with increasing living expenses.

Finally, let’s deal with the assumption that organic growth from future contributions and market returns will replace the older accounts with the younger accounts. The mandated contribution level is 11% and will continue increasing by 0.5% every year until it reaches 12% from 1 July 2025. The net total amount in superannuation has been clouded by recent events with COVID impacting savings rates (they were higher due to less consumption) and early access to super (this reduced some balances), however net contribution flows had been stable at around $10 billion per annum prior to that time and have recovered to slightly above this since the COVID period. Total benefits payments have been increasing and have increased from $20 billion to $25 billion per annum from 2018 to 2022. There was a net -3% decrease in total assets from 2021 to 2022 caused by volatility in financial markets.

So, the system is still in net positive contributions with positive inflows being supported by increases up to 12% in the mandated participation rate, we have seen flat to decreasing returns, benefits payments out of the system are increasing, and inflation is going to put pressure on the cost of living. Among all this volatility all we can say with certainty is that there is change happening, and that more monitoring is required to track how the system and regulators respond to the changes that have been identified in this paper.

With almost universal participation in some form of investment through superannuation and over 35% of Australian adults holding investments on an ASX Chess Account, direct and indirect investment in shares in publicly traded companies was a bedrock of the Baby Boomer retirement preparation phase, and it will continue to be the bedrock of wealth management for all the generations that come after it.

Cultural changes

It is important to note that as the Baby Boomers are leaving the workforce, the values and motivations of their generation are also leaving with them. It also follows then that the values of the new Millennial and Gen Z generations are going to ascend. It’s a clear generalisation, but no one would be surprised if I said that Boomers expected work environments and those who worked for them to be rigid and hierarchical and social life to be kept separate from work, while Gen Z expects work environments to be fluid and better accommodate their lifestyles and they will blend social and online lives into their work. This alone is a significant cultural change, yet it is added to an environment where the new generations live in an economic world that is far different and more challenging than what the Boomers experienced. Consider the following issues that we can see already.

Baby Boomers exiting the economy creates significant costs for the remaining generations as they stop providing free services such as family-based childcare, and they also require increased medical care. As an example, while accounting for only 21% of the adult population, half of Baby Boomers have a long-term health condition which accounts for 34% of all adults in the population that have a long-term health condition. These are costs that will need to be paid for by the younger generations.

Add to this that the Millennial/Gen Z generations also have far more grim income and financial prospects than those who came before them. A recent Pew Research study found that when asked how children in their country will fare financially when they grow up, a median of 70% of adults across 19 countries (72% in Australia) say they will be worse off than their parents. The recent burst of inflation, plus the focus on stifling wages growth that reduces their purchasing and savings power, could mean that their prospects are even more difficult. The superannuation industry does not escape this change. A 2017 study by the Financial Services Council also found that even though 70% of Millennials had a superannuation account, they are uninterested and unengaged with it.

We have a new generation entering the system that has low expectations of being able to build wealth, strong indicators that suggest that it is indeed true that they have lower economic prospects, and they are also disengaged. This indicates that there will be a considerable cultural shift in how and why the younger generations engage with the wealth management industry, and how the industry attempts to engage with them.

Patrick Salis is the CEO of AUSIEX.