Our retirement system has three pillars: the age pension, superannuation (super) and private savings, which include the family home. The age pension has been the backbone of the system for decades, super’s contribution to retirement income is increasing and the government is encouraging retirees to use the equity in the family home. In each case the rules are complex, and they interact with each other. At the same time, retirees face a retirement of uncertain length and complexity and tend not to seek financial advice because of the cost.

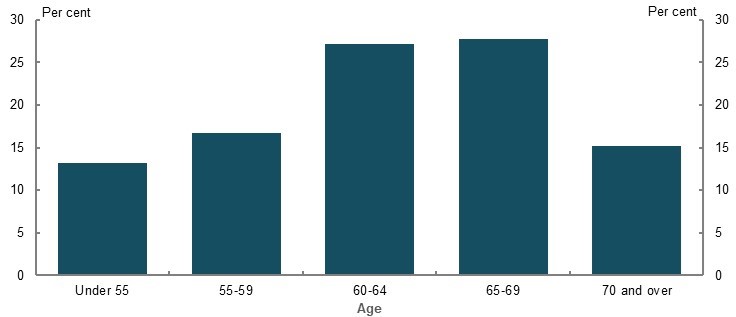

Proportion of people retiring at particular ages

Source: Retirement Income Review

An overview of the age pension

According to the Retirement Income Review, about 71% of retirees depend on the welfare payment of an age pension for all or some of their income and approximately 60% of that group receive the full pension with the remainder receiving a part pension.

In order to target benefits to the neediest, eligibility for the age pension is determined by both an assets test and an income test. Both tests are applied, and the test that produces the lower pension, is the one adopted. For retirees with substantial savings, the assets test is most relevant. The income test applies mainly to those pensioners who continue to earn an income. For a couple who own their home, the full pension is $1,547.60 per fortnight or $40,237.60 per annum. It is updated each March and September.

Under the assets test, a couple can have $419,000 in assets before their pension is reduced. Assessable assets include superannuation balances but exclude the family home. The pension is reduced by $3 per fortnight ($78 p.a.) for every $1,000 in assets above that threshold and is reduced to zero when their assets reach $935,000. There are different thresholds for singles and for renters, but the rate of pension reduction is the same for each. This is the so-called taper rate and is crucial to these considerations.

The pension is reduced by $7,800 p.a. for every additional $100,000 in assets – a rate of 7.8%. Unless those additional assets can earn at least 7.8%, the pension is reduced by more than the income earned by those additional assets. For example, a 6% return on assets of $900,000 means an annual income of $54,000 plus a part pension of $2,719.60 p.a. By contrast a 6% return on assets of $419,000 means an annual income of $25,140 plus a full pension of $40,237.60 or a total over $65,000. In fact, a couple earning 6% would need to have assets of almost $1.1 million to earn the same income as the couple with $419,000 on the full pension. That differential only widens with lower earning rates.

The reverse process also applies. A reduction in assets will increase pension income unless these pensioners earn at least 7.8%. It creates a perverse incentive to reduce assessable assets. A less punitive taper rate, as was the case prior to 2015, when pensions were reduced by only $1.50 per fortnight for every $1000 over the threshold, created more part-pensioners – some were millionaires in 2015 – but it lacked the powerful incentive for people to impoverish themselves. Treasury only counts dollars, not behavioural incentives, and the taxes any behavioural changes may generate.

How realistic is it for a retired couple to earn these high rates of income on their investments? The age pension is the ultimate annuity. It is government guaranteed, paid for life, and indexed to male wages. With this certainty, pensioners could choose to take on more risk with their own investments to generate a higher income, happy in the knowledge that any lost investment income will be replaced by increased pension. But many are very risk adverse, preferring to stick to term deposits, thereby limiting their possible income and associated lifestyle choices.

Note that under the pension income test, deeming rules are used to calculate assessable income from financial assets for pension purposes. Financial assets are presently deemed to earn no more than 2.25% of the asset’s market value. Because the actual income above the deemed amount is ignored, pensioners are free to maximize their income from those assets without penalty.

Even a part-pension is highly prized, and some go to considerable lengths to secure it. Some see it as an entitlement; a part-return of taxes paid earlier. Others value the pension health card. To remain eligible for a part age pension however, a couple’s assessable assets must be less than $935,000. Therefore, their possible income is limited by their investment return.

Family home considerations for retirees

The family home has never been part of the pension assets test and is unlikely to be included because all governments regard the issue as political poison. A higher superannuation balance will decrease the age pension, but the family home of any value will not affect it. This exemption distorts retirement decisions. Hence, a rational response for some pensioners is to reduce their assessable assets by investing heavily in the family home through renovations or upsizing.

According to the Retirement Income Review, 15% of age pensioners live in family homes worth more than $1 million, mainly in Sydney and Melbourne. There is an understandable reluctance to downsize and move to another area for several reasons. Nevertheless, the family home has real value that could be unlocked to improve retirement living standards, but many prefer to remain asset rich and income poor.

When it comes to age care, pensioners pay lower fees, the family home is only partially assessed, and the family home is free of capital gains tax (CGT) after death. Beneficiaries who inherit this asset certainly appreciate its value. Some would say this is a tax-payer unwritten inheritance.

To underline the distortion, a couple that saved $1 million in their super fund instead of the family home would be ineligible for any age pension and thereby save the taxpayer almost $1 million over their lifetimes, and as independent retirees, their age care fees will also be higher and their super death benefits may also be subject to tax.

Firstlinks has run several articles and discussions on accessing home equity and why the family home should be included in the assets test that explore these issues in greater depth.

Despite a clear unwillingness to include the family home in the assets test, successive governments have tried to encourage pensioners to voluntarily access the equity in their home.

The downsizer super contribution allows people to transfer some the proceeds of sale of the family home as an additional contribution into superannuation above the normal contribution caps. In that way they access the accumulated wealth in the family home and turn it into retirement spending. The issue is that downsizing turns part of a non-assessable asset (the family home) into an assessable asset (super) and thereby reduces the age pension.

The Home Equity Access Scheme is a government sponsored reverse mortgage scheme whereby retirees, not just pensioners, can borrow money for retirement spending against the security of their property without the requirement to make any repayments because the interest payments are capitalised. Although it does not affect the age pension, its popularity is uneven because the loan balance continues to grow until the house is sold and it is very interest rate sensitive. The retiree’s equity in their property continues to fall until the loan is repaid and that has implications for future bequests.

Governments want you to have more super

Super is designed to encourage people to save for their retirement with concessional taxation on contributions and investment returns but limiting access to those savings until retirement. The superannuation system is still maturing. The super guarantee (compulsory super) started at 3% of wages in 1992 and is not expected to reach the full 12% until 2025. Accordingly, Treasury notes that 65% of people retiring in 2020 were expected to have balances below $250,000 at retirement, but that proportion is expected to decrease to 30% by 2060.

The government would prefer retirees to have more super to reduce the cost of the age pension, but not so much that they get an unfair advantage from the tax concessions that it attracts. The debate questioning the cost of super tax concessions compared to the cost savings on the age pension, has already started. This debate often includes the easily measured tax concessions flowing to large super balances, but often ignores the fact that a self-funded retired couple saves the taxpayer over $40,000 per year. It also overlooks the fact that a couple who own their own home can have $419,000 in super and still receive the full age pension.

Compulsory super is clearly intended to reduce the cost of the age pension. From 1 July 2023, retirees will need to be 67 years of age before they can claim the age pension. However, they can access their total super balance, tax-free, from age 60 if they are fully retired. This provides many opportunities to use super savings in ways that do not translate into retirement income. For some, it means they can then afford home renovations or holidays. For others, knowing that this money is available after age 60, may mean they can enter retirement with more debt than they might otherwise.

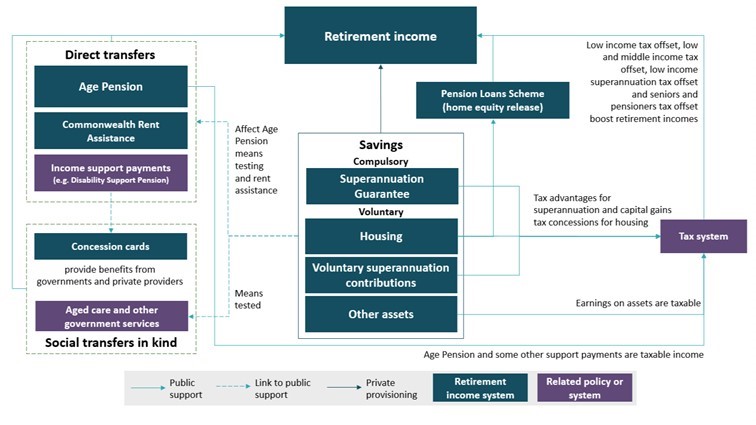

Key retirement income system interactions

Source: Retirement Income Review

Problems with the system

The age pension clearly favours homeowners over renters. Renters are allowed a higher assets test threshold, but the additional assets and government rent assistance do not cover current commercial rents. A rational response is to take a lump sum withdrawal from super after age 60 to reduce or eliminate the mortgage in retirement and optimize the age pension after age 67.

At the same time there is considerable resistance to the idea of allowing young people early access to their super to reduce or eliminate their mortgage because, with a smaller super balance at retirement, it makes their dependence on the age pension more likely.

The present system has embedded behavioural incentives that neutralize policy objectives:

- The current age pension taper rate creates perverse incentives.

- The family home is a sacred cow that distorts retirement decisions.

- Access to super before it is assessed for the age pension, means that not all super savings are used to fund retirement income.

Jon Kalkman is a former director of the Australian Investors Association. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any investor. This article is based on an understanding of the rules at the time of writing.