This is the second part of my interview with one of the fathers of the wealth management industry, the 1990 Nobel Prize Winner, Harry Markowitz. His Modern Portfolio Theory ideas are still taught in universities and business schools. In Part 2, we discussed his retail financial advice business, GuidedChoice. He is co-founder and Chief Architect, including designing the software analytics for the investment solution and heading the Investment Committee. Part 1 of the interview on portfolio selection is here.

----------

Graham Hand: Can we talk about you do with GuidedChoice? I’m especially interested in how you advise people, how you manage asset allocation and issues such as longevity risk.

Harry Markowitz: What we do is Monte Carlo analysis to get a probability distribution of how well you will do if you invest in a certain way, and save a certain amount of money. You’re familiar with Gary Brinson’s writings on asset allocation?

GH: Where 90% of your returns come from asset allocation, not manager selection.

HM: Yes. The important thing about Gary Brinson’s work, which has persuaded trillions of dollars of funds to do this top down analysis, is where you first decide to be on an efficient frontier at the asset price level. Then you figure out where you should invest, you might consider the managers to use or ETFs. The beauty of that is that people who have no ability to pick stocks can still get good advice.

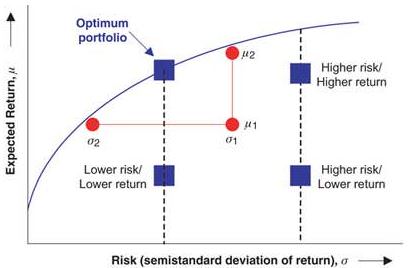

We do this top down analysis, for all our clients, we do forward-looking estimates of variances and covariances. We don’t reestimate values very often because we use long-dated series. A few years back we said we’ve got to reduce our forward-looking estimates on fixed income because we’re obviously in a low rate environment, but we don’t change equity estimates very often. We are doing principal component analysis of the factors, but it’s not completely mechanical. When it’s finished, we take all the asset classes with estimated expected return on one axis and estimated standard deviation on the other axis.

For everybody, we generate an efficient frontier at the asset class level, and we pick off 7 portfolios, number 7 being the riskiest, 1 being the most cautious. Then for specific plans, which have allowed investments, we have a separate optimisation which tries to figure out what are the real investible securities permitted by particular plans in order to match these asset classes. We take into account tracking error, expense ratio, historical alphas. For each participant, we receive a lot of data from their company, and we ask questions like, “When do you plan to retire?”

GH: So there’s a type of online questionnaire that the individual fills in? I’m wondering how you work out the client’s risk appetite.

HM: Yes, it’s interactive online, but we do not ask whether you sky dive. We look at what you already have in your portfolio, assess your current risk level, and we propose to you a portfolio. Then we show you the consequences of changing from your current one to a proposed portfolio. We show you three points on the probability distribution of how much you can spend in current dollars when you retire – in a weak market, an average market and a strong market. You can fiddle with it, you can go up the frontier, or you can save more.

GH: You have these 7 asset class portfolios with different risks, how does someone decide?

HM: You’re a client, you’ve told us when you want to retire, you’ve said at what rate you are willing to save, told us whether you have a spouse, we can see your existing portfolio. We show you a portfolio which has a similar risk level but maybe a bit more return, and we show you three points off the probability distribution showing the rate you can spend when you retire. You might not want Risk Class 4, so they try 5, and we go back and forth.

Source: GuidedChoice website.

As an aside, you should read a paper I wrote called The Early History of Portfolio Theory 1600-1960. I chose 1960 because that was when Bill Sharpe knocked at my door and asked what he should do his dissertation on. And 1600 is when The Merchant of Venice was written and Antonio said, "My ventures are not in one bottom trusted, nor to one place; nor is my whole estate, upon the fortune of this present year.” Shakespeare knew about diversification.

GH: So portfolio diversification had already happened by 1600. How far have we come since then?

HM: Well, now we know how to measure covariance. We know diversification will eliminate risks if they’re uncorrelated, but not if they’re correlated.

Another thing I should say is that GuidedChoice now has another product, GuidedSpending, which has to do with how fast you can spend in retirement. We assume your spending rate will depend how well you do in the market, and we ask you for two consumption levels: upper level where you can put away any surplus for a rainy day, and a lower level where you have to see if you can hold out for a while. Depending on how you set your levels, plus all the other factors, we assign a probability distribution on the rate at which you can spend when you retire. For any time pattern of consumption, we assign a utility based on the average consumption you can achieve.

GH: But how do you plan for how long a person is going to live?

HM: Currently, we assume you will drop dead precisely 10 years after your actuarial time, but I have been promised some day we will have a stochastic model.

GH: So you use actuarial life tables. What do you think about the basic default savings plans, such as the 60/40 model or lifecycle funds with more allocated to the defensive asset over time?

HM: The problem with 60/40, it’s a little chicken for people early on, it’s not right for everybody. 90/10 might be best for a young person. The problem with lifecycle is I’m 85 and I have more in equities than I’ve ever had, but I have a wealth level that means I am many standard deviations away from not being able to eat.

GH: So you need to consider your income-earning ability and other factors, not just your age.

HM: You need to look at the probability distribution of what they can spend, what they can earn, how long they will be employed. Our models will always be grossly inadequate because there are more things on heaven and earth than we can ever capture in our models. We have to do the best we can but we get a lot closer than 60/40 for everybody.

GH: What do you think of the merits of Tactical Asset Allocation where someone takes a view on the market and changes the asset allocation?

HM: There’s my official view and my unofficial view. My official view is that nobody seems to be very good at picking the market. But it does seem plausible that when price earnings ratios are historically high, we should lean towards less to equities. In my own funds in 2007, I sold my ETFs, I didn’t get out of equities completely, and I went back in in December 2008 expecting a January effect. Which came in March. On some occasions, it has merit. But if someone reads a weekly newsletter about whether you should be betting up or down this time, going in and out, you’ll lose money on average over the long run. There’s a wonderful behavioural finance guy, Terrance Odean, who studies the track records of individual investors, and he finds both active and passive investors gross roughly what the market makes, the active do worst due to brokerage.

You know, I’m writing another book, in 4 volumes, first is already at the publishers, McGraw-Hill. The next volume is due March 2015, then 2017, then 2019.

GH: That’s a good note to end on. Thanks very much, I really appreciate it.