Many investors see Chinese property as an asset bubble that is popping; we see things differently (as discussed here). If anything, it’s a good example of an ‘anti-bubble’ and presents a compelling opportunity for investors like us.

In his excellent book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, Ray Dalio gives a simple framework for spotting bubbles:

- Prices are high relative to traditional measures;

- Prices are discounting future rapid price appreciation from these high levels;

- There is broad bullish sentiment;

- Purchases are being financed by high leverage;

- Buyers have made exceptionally extended forward purchases (e.g. built inventory, contracted for supplies etc.) to speculate or to protect themselves against future price gains;

- New buyers (i.e. those who weren’t previously in the market) have entered the market; and

- Stimulative monetary policy threatens to inflate the bubble even more (and tight policy will cause it to pop).

Few of these have been present in China for over a decade. Yes, there is leverage in the system, but sentiment is terrible, asset prices are generally moderate-to-low, and officials have been seeking to curtail activity, not stimulate it. Put another way, China looks very much like a place that has had a financial crisis in a long, drawn-out fashion since the heady days of high equity prices and exuberance of the late 2000s.

It seems to us reminiscent of Japan in the early 2000s – deep into a multi-decadal bear market and regarded as hopeless by most. The Nikkei 225 went on to triple over the next two decades.[1]

But what if there is no catalyst? Japanese equities have provided us with decent returns (six-fold returns in 20 years in our Japan Fund[2]), with Japanese equities de-rating the entire time – earnings and dividends drove all of the returns, even as Japanese equities’ multiples declined. This is the nature of anti-bubbles.

We think we see something similar in Chinese residential property. Markets work in cycles, and this may well be what the bottom of a market cycle looks like.

Central to all clichés is a kernel of truth. Property prices in China have fallen, as has new build activity, and consumer confidence is low. Note how these conditions are the reverse of Dalio’s bubble checklist above. Commentators 'know' that the industry is 'a Ponzi scheme' in the grip of 'a slow-motion crisis' (see here and here).

And yet we have owned property developers in China and made money. Perhaps we are reckless, taking huge 'risks' by owning such companies? Or perhaps, when everyone 'knows' how terrible the outlook for an industry is and the facts belie this 'knowledge', one has found an anti-bubble, and can commit capital with low risk, despite the discomfort of swimming against the tide?

Facts belie the negative sentiment

In the case of the Chinese property market, the facts do indeed belie the prophesies of doom.

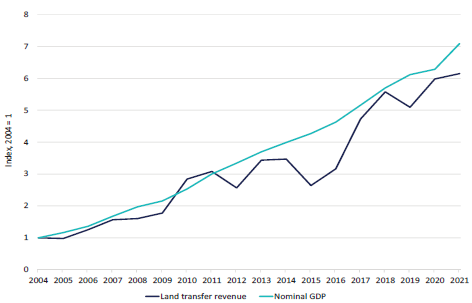

Contrary to most commentary, Chinese property prices have risen in an unremarkable fashion, both relative to other countries and relative to incomes or nominal gross domestic product (GDP). For instance, real house prices in China appreciated at a slower rate than those in Germany in the decade to the end of 2020. Government revenue from land transfers, which is at the core of the Chinese residential property industry, has grown more slowly than nominal GDP over the last 17 years.

Fig. 1: Chinese land transfer revenue versus nominal GDP, indexed

Source: citi

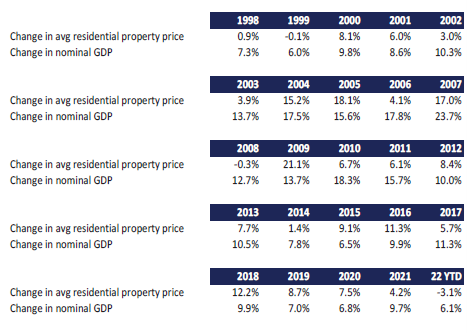

Further, Chinese house prices, as collected by the equity research team at citi, have appreciated by far less than nominal GDP growth since 2005.

Fig. 2: Chinese house price growth versus nominal GDP, change year on year

Source: citi, FactSet Research Systems.

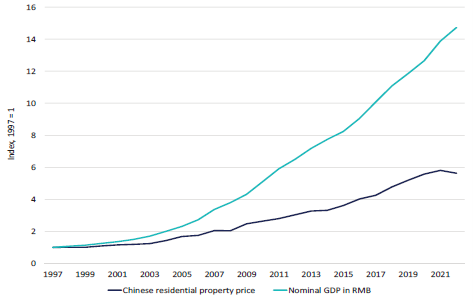

Fig. 3: Chinese house price growth versus nominal GDP, indexed

Source: citi, FactSet Research Systems.

Simply put, Chinese property prices have increased a great deal in the last few decades, but why wouldn’t they in a fast-growing economy with rapid household income growth and a colossal urbanisation drive?

Further, Chinese mortgage rates have remained high by global standards, never falling below 4.7% and remaining well above 5% since 2018 for borrowers with one property, with considerably higher rates applying for purchasers of a second property.[3] Chinese borrowers require large down-payments for houses, with first-home buyers requiring 30% down-payments and second- and third-home buyers needing more equity still.[4]

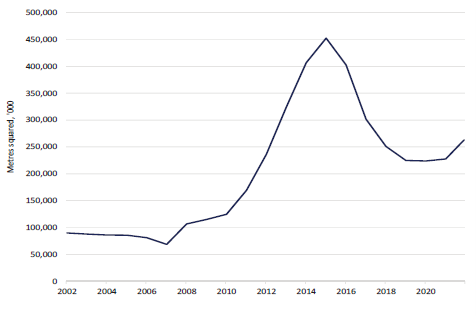

There is no evidence of any meaningful glut of properties in China.

Has there been malinvestment? Yes.

Is there evidence of a nationwide excess of housing units? No.

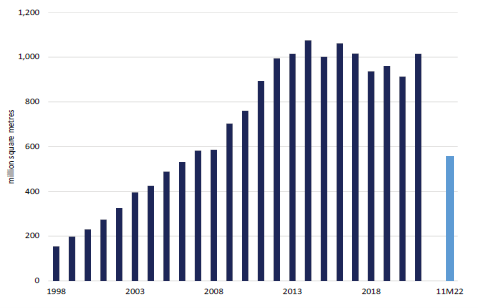

Fig. 4: Vacant residential floor space waiting for sale

Source: Citi. Note 2022 data is to November.

What about China’s ‘ghost cities’?

But what of the tens of millions of empty apartments so frequently reported on by the Western media regarding China? Well, there are likely many millions of homes built in poorly conceived projects by property developers across China – this should be no surprise. Property developers build unsuccessful projects in every jurisdiction. There are around 400 to 500 million households in China in our estimation, so when we see breathless reporting of “50 million empty homes in China”, that would be roughly in line with the 10% unoccupied homes in Australia, for instance.

Prior to 1994, there was in effect, no private ownership of housing in China, and while housing was provided universally, residential area per capita in urban areas was a tiny 6.7 square metres (sqm) on average, generally with shared bathroom and kitchen facilities.[5] Since that time, China has completed just over 17 billion square metres of housing,[6] in the largest urbanisation in human history.

Let’s break down that number.

Multiplying this out gives us an average house size of approximately 100 sqm in urban China, and implies that of the 875 million people living in Chinese cities, only 438 million are living in a modern (post-1994) dwelling.

Put another way, if China is to house all of its current urban population in modern housing stock, it needs to double its entire modern housing build out, ignoring any replacement of existing housing.

Fig. 5: Chinese residential construction completions in metres squared

Source: citi.

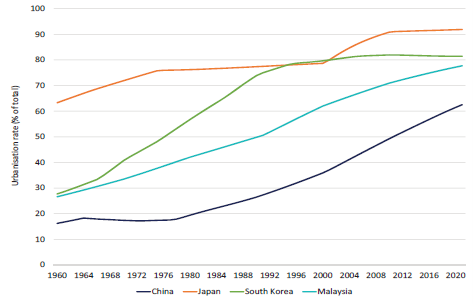

Further, China’s urbanisation rate of 62.5% is low compared to other Asian countries (see Fig. 6). If we assume that China reaches an urbanisation rate of 80%, in line with other developed and middle-income Asian nations, approximately 200 million people will enter Chinese cities in the coming two decades or so, even assuming a gradually declining population.

All told, China may require a further 25 years of current rates of residential construction to house its urban population in modern housing.

Fig. 6: Urbanisation rates, China versus select Asian high- and middle-income nations

Source: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=CN.

The sector needs ongoing reform

Since a series of reforms in the 1990s, culminating in the cessation of public renting of housing for workers in 1998, China has transformed from a country of workers who rented an abode from the government – this being a nominally Communist country after all – into a nation of homeowners. At 90%, China has among the highest rates of home ownership in the world.[7] Therefore, the entire modern housing stock of China has been grafted onto a previously existing housing stock of low-quality shared accommodation. One of the most important issues in China is that the majority of the population still live in poor-quality, pre-1990s era housing – with massive ongoing construction required.

China needs ongoing reforms to allow for dignified rental conditions for workers in cities, not least for migrant workers (those without hukou). Further, China likely needed to slow the rate of home construction from the one billion square metres it was building in recent years (see completions data in Fig. 5) and has been at pains to curb property speculation for years.

An element of the Chinese residential property reform program has been the direct control of new residential property prices, which we see as both heavy-handed and counterproductive. However, the 'three red lines' policy designed to curb excessive financial leverage among developers is sensible, albeit difficult to achieve without causing severe disruption to the broader industry, as has occurred. Of the thousands of property developers in China, only a handful meet the 'three red lines' rules against excessive gearing. The Chinese Communist Party has clearly stated that it will support conservatively financed, larger property developers even as it strangles smaller, highly indebted operators.

We think this is reminiscent of the reforms of the insurance industry and the broad drive against overcapacity in heavy industries like steel, coal and aluminium: larger, better-run operators tend to be advantaged over smaller players as the state cleans up excess capacity and irresponsible practices in previously fast-growing industries.

So, when we observe a better-quality Chinese property developer like China Resources Land trading at mid-single-digit PEs, paying a 5% dividend yield, with a strong balance sheet, amid a regulatory push to eliminate its smaller, more indebted competitors, we see opportunity. This is the reverse of a bubble. This is an anti-bubble, where the crowd perceives 'un-investability' despite a long track record of success, data to suggest that property development will be required in China for decades to come, and a commitment by the CCP to employing existing property developers to meet that need.

None of this is without risk; anyone who believes there is no risk in owning an equity is sadly mistaken. But investment is about balancing risks. Large, lowly indebted Chinese property developers appear to offer an exceptional opportunity, in our view.

1. Source: FactSet Research Systems.

2. Source: https://www.platinum.com.au/Investing-with-Us/Prices-Performance. Fund returns are net of accrued fees and costs, are pre-tax, and assume the reinvestment of distributions. Historical performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Source: Platinum Investment Management Limited.

3. CLSA

4. CLSA

5. China People’s Daily: http://en.people.cn/n3/2018/1213/c90000-9528155.html; Fang et al, “Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom”, NBER Macroeconomics Journal, vol 30, 2015, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685953

6. Source: citi, data to November 2022.

7. Huang et al, “Home ownership and the housing divide in China”, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7546956/

Julian McCormack is an Investment Analyst (Retail) at Platinum Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. For more articles and papers by Platinum click here.

View Disclaimer: This information has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006, AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management (“Platinum”). While the information in this article has been prepared in good faith and with reasonable care, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, adequacy or reliability of any statements, estimates, opinions or other information contained in the article, and to the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by any company of the Platinum Group or their directors, officers or employees for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. Commentary may also contain forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements have been made based upon Platinum’s expectations and beliefs. No assurance is given that future developments will be in accordance with Platinum’s expectations. Actual outcomes could differ materially from those expected by Platinum. The information presented in this article is general information only and not intended to be financial product advice. It has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s or class of investors’ investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making investment, financial or other decisions. You should obtain professional advice prior to making any investment decision. You should also read the relevant product disclosure statement and target market determination before making any decision to acquire units in the fund, copies of which are available at www.platinum.com.au/Investing-with-Us/New-Investors. © Platinum Investment Management Limited 2023. All rights reserved.