It is remarkable that, more than 25 years after the key planks of today’s superannuation system were put in place, we still have not defined the purpose of superannuation, despite recent unsuccessful attempts to legislate an objective.

Indeed, a better aim for our politicians might be to establish an objective for the overall retirement income system, encompassing age pension and related benefits, and compulsory and voluntary superannuation. Looking at the whole system, rather than just superannuation or any other component, would help promote better integration of the various components over time. We hope to see this matter addressed by the upcoming Retirement Income Review.

More focus needed on the spending phase

In the meantime, it should not be contentious to assert that superannuation savings accumulated during working years should be spent down (ideally, as a regular income) in the years after employment ends. But too often even this limited purpose is not reflected in public discussion of superannuation and the retirement system. Often there is an assumption that assets accumulated for retirement are not to be drawn down during the retirement years, but instead act as a ‘capital base’ to generate investment earnings which can be spent but otherwise should remain untouched.

We saw this thinking in the discussion of Labor’s policy to discontinue refunding of excess franking credits. It was clear many retirees or their advisers considered their ‘retirement income’ to be the dividend stream (including franking credits) generated on their share portfolio.

An unrealistic strategy

We should be wary of allowing a ‘spend the income’ mindset in retirement to take root for a good reason – for most retirees, it is simply unrealistic. Living off the interest income from term deposits or the dividend income from a share portfolio sounds attractive but for most retirees (who have little in the way of income-producing assets outside superannuation) this strategy is unlikely to produce an income they might regard as adequate, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Achieving a target retirement level using a ‘spend the income’ strategy

|

Target retirement level (ASFA Comfortable)

|

Required balance if invested in

|

|

Term deposit

|

Australian share portfolio

|

|

Single ($43,601)

|

$2,777,000

|

$703,000

|

|

Couple ($61,522)

|

$3,919,000

|

$992,000

|

Notes:

- Term deposit rate: 1.57% pa (average of advertised rates for 12-month term deposit on $100,000+ for the four major banks in September 2019).

- Dividend yield: 6.2% pa (average gross dividend yield on ASX200 over 12 months to September 2019, including franking credits).

To achieve an ‘ASFA Comfortable’ income a couple adopting a ‘spend the income’ strategy would need to have a retirement balance of $3.9 million if investing in term deposits, or a lower amount of around $1 million if invested in a higher-yielding (but riskier) Australian share portfolio.

Table 2: Median superannuation balances in retirement

|

Age

|

Males

|

Females

|

|

65-69

|

$172,914

|

$165,857

|

|

70-74

|

$182,272

|

$170,885

|

|

75+

|

$132,324

|

$131,061

|

Source: ATO Taxation Statistics 2016-17

These amounts are well above the median superannuation balances by Australians of retirement age, as shown in Table 2. This strategy makes sense only for the relatively wealthy few.

Minimum drawdown rules, OK?

The minimum drawdown rules (MDRs) that apply within the superannuation environment are designed to ensure account balances (including capital) are spent over the pension phase.

While MDRs only specify a minimum amount, many public offer funds still offer little guidance on drawdown strategy in retirement beyond disclosing the relevant percentages. Many retirees commence drawing down their account at the MDR, and a high proportion of members draw down at minimum rates throughout the pension phase, particularly for members with balances at or below the median.

Some funds cite concern about regulatory constraints on providing advice and limited information about their retirees as constraints on offering more tailored drawdown guidance. However, in many cases, a minimum drawdown strategy is actually too conservative, deferring spending that could contribute to the quality of life in early retirement and increasing the chance of leaving unnecessarily large amounts behind on death.

Drawing down well

While longevity protection solutions (more on these later) can address underspending more directly, it’s possible to improve things with careful design of the drawdown strategy used by members.

Consider the following three strategies to drawing down from an account-based pension:

- In line with the MDRs (Minimum Drawdown strategy)

- A constant drawdown each year, set at a level expected to last until age 90 (i.e. life expectancy plus 3 years) (Constant Drawdown strategy)

- In line with a modified set of drawdown factors based on life expectancy at each age + 3 years, but with a limit on the amount by which the drawdown reduces over any year (LE+3 strategy).

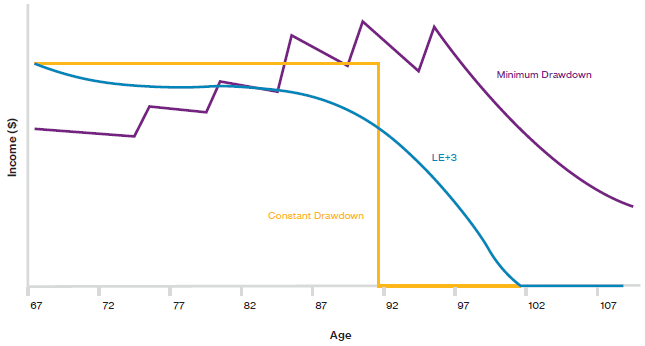

Chart 1 illustrates the pattern of income expected to emerge under each strategy (the actual drawdown level will vary depending on actual returns rather than the constant return used in this illustration).

Chart 1: Patterns of income under three drawdown strategies

The Minimum Drawdown strategy provides lower income early in retirement but lasts longer than the other strategies. While ensuring income is available in advanced old age is a desirable feature, many retirees may prefer to bring more income forward to the earlier, more active years of retirement.

Of course, there is a trade-off: a faster spending strategy means retirees can enjoy more of their savings, but equally increases the chance that they will be left without retirement assets if they live longer than expected. Setting an appropriate drawdown strategy can be seen as an exercise in balancing two risks to the retiree – running out of money before death, or ‘ruin’, and leaving amounts behind on death that might be regarded as excessive, or ‘wastage’.

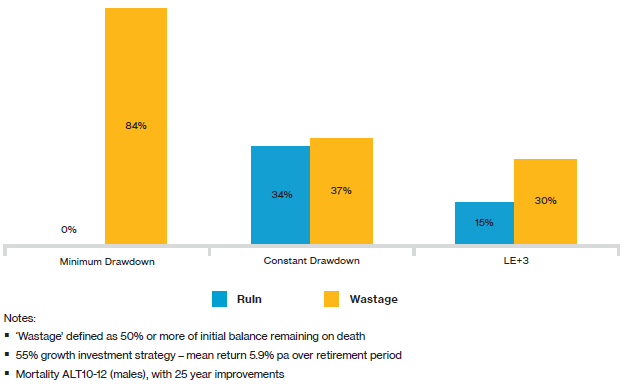

These risks are shown in Chart 2 below, for each of the three drawdown strategies considered.

A Minimum Drawdown strategy, while having a zero risk of ruin, has an unacceptably high risk of wastage, whereas under a Constant Drawdown strategy, ruin risk becomes the concern. Many funds would still baulk at endorsing a strategy with a one-third risk of running out before death.

This suggests a middle ground, like the LE+3 strategy, can provide a better balance of these risks. Research we have conducted in this area shows that this strategy can be further improved by additional modifications to the drawdown algorithm (such as floors and ceilings to reduce large variations in year-on-year income).

Chart 2: Likelihood of ‘ruin’ and ‘wastage’ under different drawdown strategies

Ultimately, no strategy alone can ensure a stable income for life. Ideally, as well as developing a default spending policy for retirees, funds would offer a complementary longevity product (such as a deferred annuity) to provide ongoing income where a retiree outlives their savings.

So, what can be done?

Superannuation funds and the industry generally can promote spending down of balances smoothly during the retirement phase. Some ideas are:

- A retirement income objective: Developing an objective with substance will be contentious, as industry stakeholders and other participants will have differing views. For instance, should our system aim to deliver poverty alleviation, age pension supplementation or a standard of living defined by reference to working life earnings? Whatever benchmark is set, an objective should provide that retirement provision be in income form, and capital balances be spent down over retirement.

- Retirement income estimates: Providing estimates of projected retirement income during the accumulation phase (particularly as members approach retirement) promotes the primary aim of superannuation as spending in retirement. These estimates are currently provided by many funds but are not universal. Ideally, income estimates should be made mandatory, with some sensible limited exceptions at the fund and individual member level.

- Careful use of the term ‘income’: Language matters. In communicating with retirees we often see ‘income’ used to denote both investment earnings (such as dividends, rent, interest etc.), and the income received from a fund during retirement phase. This dual usage can cause confusion and promote the ‘spend the earnings’ concept described above. It’s often better to use ‘drawdown’ or similar terms to refer to amounts paid to retirees in pension phase.

- Well-designed drawdown rules: Funds should review their default drawdown offerings to ensure they are not too conservative and do not promote inappropriately low spending by retirees.

- Better retirement products: Ultimately, most retirees with meaningful balances will spend their savings more confidently earlier in retirement only if they are sufficiently comfortable that they will not run out of money in advanced old age. The continued development and promotion of longevity protection products which can provide this comfort remains a high priority for the industry.

Nick Callil is Head of Retirement Solutions, Australia at Willis Towers Watson. The information in this publication is general information only and does not take into account your particular objectives, financial circumstances or needs.