As an active value manager, we like investing in companies where we believe there are hidden assets not being properly valued by the market. Sometimes it takes a demerger for parts of a business to really show their worth.

Demergers often work

We have looked at all the significant Australian corporate demergers over the last 20 years to determine whether they added value and if we could glean any insights from the trends this analysis revealed. Intuitively, splitting a company in two shouldn’t create any additional value given the cost of the transaction and the ongoing costs associated with duplication of overheads.

However, our research has indicated that some demergers create value. Broadly, we found that the continuing entity – the larger portion of the split up that often retains the CEO and Board of the previous company - narrowly outperformed the S&P/ASX 200 in the following couple of years. However, the demerged entity outperformed this market significantly in the following two years. On our estimates the median outperformance is around 35% over two years, although there is a massive range in outcomes.

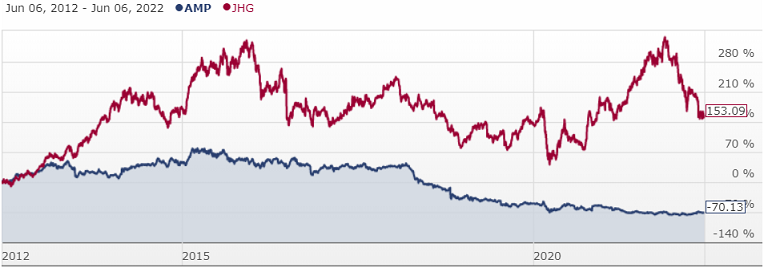

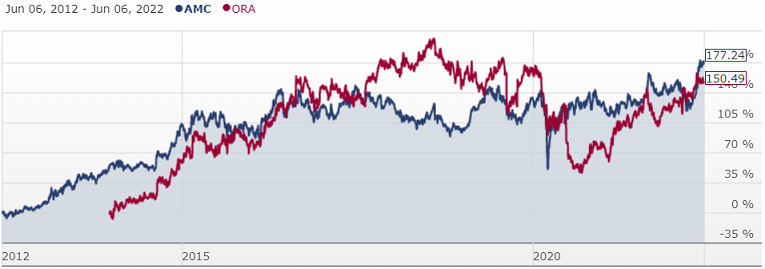

Some examples of demerged entities which have performed very well over a longer period were Dulux (spun out of Orica in 2010), Treasury Wine (spun out of Foster’s in 2011), Henderson (spun out of AMP in 2003, figure 1) and Orora (spun out of Amcor in 2014, figure 2).

Figure 1: AMP (blue line) and Janus Henderson Group (red line)

Figure 2: Amcor (blue line) and Orora (red line)

However, demergers don’t always go well. Paperlinx (spun out of Amcor in 2000) and Onesteel (spun out of BHP in 2000) did not end well for shareholders. The range of outcomes is significant with Asciano (spun off from Toll in 2007) underperforming by 49% in the following two years while Australian Wealth Management (spun off from Tower in 2005) outperformed the market by almost 200%.

When are demergers successful?

Our analysis of demergers concluded that there are two fundamental reasons behind their success.

- Splitting the company into two bite-sized pieces increases the chances that one of the two companies will get acquired. Of the 28 demergers we analysed, 18 saw at least one of the two parts taken over, generally within a couple of years.

- The demerged entity received more attention once it had been demerged. Commenting on Orica’s successful demerger from Dulux we noted (Perpetual SHARE-PLUS Long-Short fund update, January 2020):

"Capital allocation, human resources, marketing etc. would be completely different between these two businesses (paint and explosives). Once demerged, attracting and retaining top quality management is made easier as employees of the demerged entity can be incentivised with equity in an entity in which you can make a difference rather than being part of a larger conglomerate.”

Senior staff choose where to work

Our view is that while CEOs or chairpersons usually won’t reveal which division of the company they are most excited about, they all have their favourites. Capital is a scarce asset and, when push comes to shove, capital will tend to gravitate to the ‘favourite child’.

Conversely, when there are extra corporate costs, they will tend to be shoved over to the less-favoured division, which has the impact of understating the earnings of this entity. After a demerger, the CEO and chairperson are eventually forced to make a choice about which division is their favourite as they must make the decision about where they will remain.

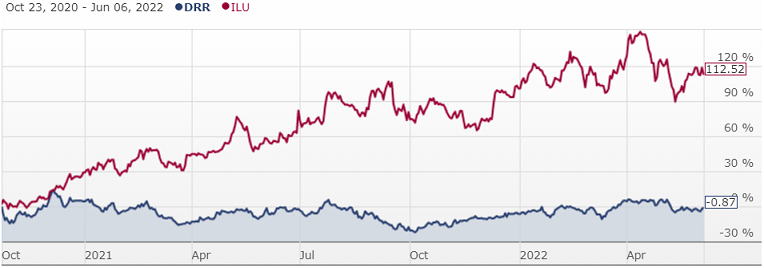

In the recent demergers of Woolworths/Endeavour, Graincorp/United Malt and Iluka/Deterra, the CEO and chairperson both decided to go to Woolworths, United Malt and Iluka respectively. What typically then happens is the ‘ugly duckling’ company will get a new CEO, a new board and generally a new culture. Divisional management is often promoted to the C-suite and there emerges an almost underdog status within the new company.

We think that some of the outperformance that may follow can be explained by this renewed focus a demerged entity gets from its leadership group.

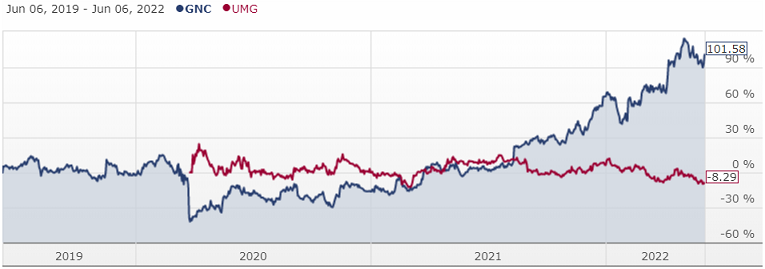

And this runs potentially deeper over time. The new team running the demerged business is unshackled from corporate overheads and other frustrating constraints. This can give way to a new culture which is hungrier, leaner and more agile. The demerged business can make the right investments and seize on market opportunities without having to prepare a pitch book for head office. We have observed from the performance of recent demerged entities like Endeavour, Graincorp and Deterra how a new culture and lease on life can take hold post demerger.

Figure 3: Woolworths (blue line) and Endeavour Group (red line)

Figure 4: Graincorp (blue line) and United Malt Group (red line)

Figure 5: Deterra Royalties (blue line) and Iluka Resources (red line)

Why lifecycle matters in company demergers

It is easy to think that some companies are natural market leaders with a great culture baked into them while other companies are badly run with a poor culture that is likely to be terminal to the business. Most companies are somewhere between these two absolutes. They go through periods of good decision making and periods of poor decision making.

Poor decision making often occurs when things are going well. Either the cycle is in the company’s favour, or the management team is basking in the glory of some previously-astute decision making. We believe the contra is also true. When people or companies have their backs against the wall, management teams tend to make their best decisions.

One example is the supermarket sector in Australia. While there are smaller competitors competing for market share, it is essentially an oligopoly with Coles and Woolworths. The last couple of decades has seen the ascendancy in terms of size, profitability and share price swing between the two heavyweights. We have observed an almost seven-year cycle as each of the major retailers moves from 'outhouse to penthouse' relative to the other and vice versa.

When Woolworths had the ascendency in the mid to late noughties, it focussed on rolling out new stores and maximising short-term profitability through price increases. It thought it was a good idea to start a new hardware business, Masters, from scratch. This ended badly for shareholders as the company stretched its balance sheet and, in our view, got distracted away from their core business of selling groceries.

However, this is when we observed the board and new management start to make smart investment decisions. These included shutting down Masters, taking the short-term profit hit by improving their service and dropping prices. It also invested in the store network and its supply chain, developed a best-of-breed online offering, and demerged their bottle shop and pubs business, Endeavour.

This example illustrates one of the reasons that demergers tend to work. They are executed when a company is going through that part of its lifecycle where it works out that it cannot be all things to all people. Our observation is that this tends to be a decision made by a humble CEO and board who are focussed on shareholder value and understand what that company’s core skillset.

Markets prefer pure plays

A final point on successful demergers is that they often work because the market ascribes a higher value to a 'pure play' company than a division within a conglomerate. For us, the fact that market participants are unwilling to assign the same valuation to the same business within a corporate structure as it would if it were to be standalone creates opportunity. When the sum of the parts is worth materially more than the market value, it may make sense for the company to demerge to realise that value.

Further, retail investors often follow a specific investment theme and this may break down when assessing a company which has two divisions with materially different investment traits. Take Graincorp pre-demerger as an example. The malt business (subsequently called United Malt) was perceived to be a 'low growth compounder'. The rest of Graincorp would be put into the 'deep cyclical' camp. The low growth compounder investors didn’t like the volatility associated with the cyclical part of the business and the deep cyclical investors didn’t like the boring United Malt business as it diluted the cyclical leverage.

By separating these different businesses, completely different shareholders are attracted to the two companies over time. Management can then run capital management and make investments based on its specific earnings stream and shareholders preference rather than a hybrid of the two.

While this is a poor reason to initiate a demerger in isolation, it is an explanation as to why the right demergers tend to work. As value investors, we like finding companies like these hidden gems within larger conglomerate companies where the market has been unwilling to ascribe a proper value.

Anthony Aboud is a Portfolio Manager and Sean Roger is a Deputy Portfolio Manager at Perpetual Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article contains general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Stock charts are provided by Morningstar.

For more articles and papers from Perpetual, please click here.