Both in Australia and globally we have seen a real step up in share buy-backs over the last few years. With the world awash with capital and interest rates continuing to fall, it becomes extremely tempting for boards and management to justify borrowing money at very low rates and using that capital to buy-back shares.

Like all capital management decisions, the decision to buy-back shares are more art than science. Some buybacks are a good tax efficient way of returning capital to shareholders following an inflow of capital like an asset sale. Using more debt in a capital structure can improve efficiency and return on equity (ROE) which is not a bad thing if the numerator is sustainable.

However, we feel that the short-term share price and earnings per share benefits coming from a buy-back need to be weighed up against the medium to longer term capital requirements. Having a good understanding of the cyclicality of a business, were we are in the cycle, disruptive threats, contingent liabilities, operating leverage, financial leverage and other tail risks is extremely important when making the decision.

Why do the market participants like share buy-backs?

Earnings per share (EPS) accretion

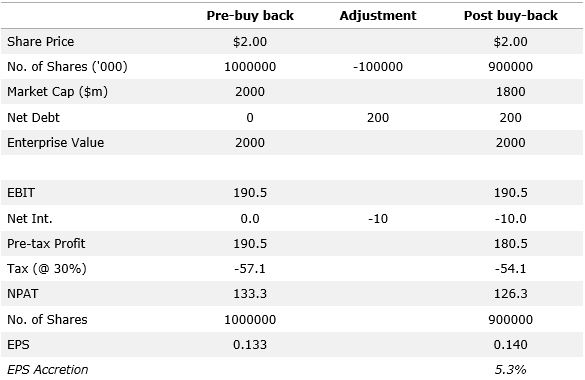

Let’s start with a hypothetical example. Imagine a $2 billion (1 billion shares at $2/share each) company which is trading at 15x P/E announces a buyback of 10% of its shares borrowing money at 5% to complete the buyback.

Imagine, for ease of calculation, that this company is ungeared.

Source: Perpetual

Same P/E ratio, share price will rise 5.3%

The enterprise value of this company does not change. All that the buy-back has done is to change the capital structure from being 100% equity to having some debt in the capital structure. However, due to the fact that the post-tax cost of interest (3.5%) is lower than the post-tax earnings yield (6.7%), conducting this buyback is earnings per share accretive.

Assuming the company remains on the same P/E ratio, the share price will go up by 5.3% all other things being equal. This magic is why some people refer to buy-backs as financial engineering. It is particularly powerful in the current investment climate where low interest rates make the cost of buybacks cheaper. Given the market is dominated by quants and momentum funds, who place a higher value on companies which demonstrate positive earnings per share momentum, the impact of EPS upgrade is magnified in the share price.

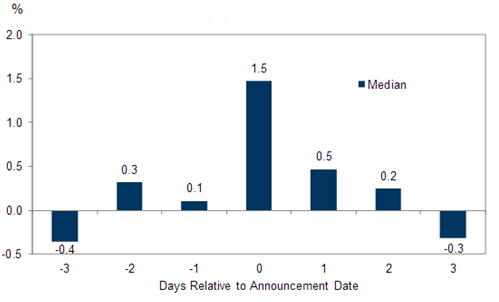

Moving from theory to practice, the market generally responds positively to the announcement of buybacks.

As can be seen from the below chart on the day of the announcement and the proceeding two days the average share price movement for the companies we have analysed in Australia is +2.2%. We believe that is statistically significant.

Price returns around buy-backs announcement

Source: Goldman Sachs

When Lend Lease announced its interim results in February 2018 one of the bullish analysts wrote in his note: “The highlight of the result was the announcement of the $500 million buy-back. While only marginally accretive (c4%), it signals confidence in the cash flows of the business.”

Four key reasons cited when companies buy back stock are:

- EPS accretion: As demonstrated above, when the cost of debt is less than the earnings yield, a buyback is EPS accretive.

- Capital efficiency: Often boards justify a buy-back by talking about an efficient capital structure. I am not sure exactly what this is. Clearly, if a board judges that the current earnings are sustainable, and the level of growth capital and innovation spend will be easily funded by the cash being generated by the business, then a buy-back could make sense. However, as we will demonstrate later in this note, short-term capital efficiency targets can lead to poor medium-term capital management decisions.

- Shows the board’s confidence in cashflows/valuation: Another positive often touted is that a buy-back gives an indication from the board that they think the shares are cheap and that they somehow have a better view of the cashflows than the market price is assuming.

- Another buyer in the market: The market does get excited that there is another buyer looking to accumulate the stock. This should provide some stock price stability and support.

The other proponents of buying back stock are the CEO and senior management. Not only does the announcement of a buy-back spark a share price jump, but most CEOs in Australia have short- and long-term incentives which are based on total shareholder return (TSR) and EPS. What’s more, the average CEO in Australia has a tenure of less than five years. This does not give a heap of motivation to think about long term value creation or tail risks facing the company.

Therefore, they are heavily motivated to buy-back shares and less motivated to spend capital on innovation and growth where the returns are more long dated and harder to calculate. This is a tough position for a board to be in. They have pressure from some shareholders and most of the senior management team to buy- back shares. While this may be the right option, we feel that historically it has not always been the right option.

When buy-backs go wrong

1. National Australia Bank (ASX:NAB) buys back shares at $40.94 and raises two years later at $21.50

In November 2006, NAB announced at its FY06 results a $500 million buy-back because of its “strong capital position and commitment to active capital management”. Then on 31 January 2007, NAB increased the buy-back by $700 million to make it a $1.2 billion buy-back. In the end of a period from November 2006 to May 2007, NAB bought back $1.2 billion worth of shares for an average price of $40.94/share. This was a price well above where the company announced the buy-back.

In the 2007 annual report which was released later in the year, the CEO and senior management team all received short-term incentives (which were based amongst other things on total shareholder return) which exceeded their target incentives. Then in July 2008, the CEO was replaced. In July 2009, the company raised $2 billion at $21.50/share. That is almost half the price the company bought back shares two years previously.

Now, this could be seen as being a little unfair in the context of the GFC. This caused a liquidity crunch in Australian banks which are reliant on offshore wholesale funding and all banks were forced to raise capital. However, this sequence of events highlighted a few things.

First, this quest for active capital management and a desire to return excess capital to shareholders tends to be calculated assuming current conditions prevail over the medium term. This is usually not the case and during the good times, banks should build excess capital to keep them in good stead during the bad times.

Second, it shows how incentivised the CEO was to maximise the short-term share price performance and the buy-back seemed to be a good way to achieve this goal.

2. Bluescope (ASX:BSL) buys back $707 million at $6.10 and raises $2.4 billion at $0.40 -> $3.10 three times in next five years

From the time Bluescope was spun off from BHP in July 2002 till June 2006, the company was generating good cashflow and was using its cashflow and balance sheet to buy back shares. In August 2006, the company’s first page of the presentation took pride in the fact that it had bought back $707 million worth of shares (at an average price of $6.10) since listing and had paid $1.1 billion dividends. In FY06 the company had bought back $95 million worth of stock at an average price of $7.02. At the time of the results, the company also announced that the CEO would retire and be replaced in November 2007.

At the time this buy-back did not seem terribly controversial. However, when the company went on an acquisition spree in FY08 (Smorgan Distribution and IMSA Steel), it overstretched itself at peak margins.

Following these buybacks, dividends, ordinary dividends and acquisitions, steel spreads collapsed and Bluescope were forced to have three equity raises in three years.

- December 2008: Raised $413 million at $3.10

- May 2009: Raised $1.4 billion at $1.55

- November 2011: Raised $600 million at $0.40

BSL share price

Source: IRESS

Not only was this extremely dilutive for existing shareholders, but it meant that Bluescope couldn’t take advantage of investing and acquiring at the low end of the cycle.

The main lessons from this is when you are running a highly cyclical company with massive operating leverage and a key revenue driver which is outside of your control, you probably don’t want to have a pretty underleveraged balance sheet, especially at the top of the cycle. Buying back shares may seem logical based on the earnings multiple and apparent strong cash generation, but we feel that this can be fraught with danger, as Blue Scope showed.

3. Lend Lease (ASX:LLC) buys-back @ $17.48 average, cancels buy-back @$12.85

In February 2018 Lend Lease announced a $500 million buy-back due to the strong cash position, solid profit growth and resilient balance sheet. The market cheered the announcement with one analyst commenting that it was the highlight of the result. “While only marginally accretive (c.4%), it signals confidence in the cash flows of the business.”

The company was buying back all the way through to the Annual General Meeting (AGM) on 9 November 2018 when it had bought back $312 million of the $500 million at $18.40 average price. At the AGM, the company revealed a profit warning due to its underperforming engineering division, including taking a $350 million provision and conducting a comprehensive review. Given the company bought shares back the day before, this revelation must have come out of the blue. The stock fell 18% on the back of the profit warning.

The company then announced its interim result in February 2019 where it revealed operating cash outflow of $824 million and a $1.1 billion increase in net debt over a six-month period. The company also revealed that it would not be completing its buy-back. The shares closed that day at $13.28/share.

The big lesson for the Lend Lease board was to understand that they are a developer as well as an engineering company which constructs large fixed price contracts for clients (typically government clients). Cashflows in these sorts of businesses are extremely lumpy. If an engineering company gets the pricing or the conditions wrong on a fixed price contract, it can be catastrophic to cashflows. What tends to happen is that the client will stop paying once the contracted price has been paid. However, the construction company continues to have cash go out the door so as to complete the project to the client’s specification. This means that the balance sheet at a point in time can deteriorate quickly.

Conclusion

When a company announces a buy-back, investors should not read too much into it as a signal for value. Boards have not traditionally been good judges of value or predictors of issues as has been demonstrated above.

However, not all buy-backs are bad. We believe that in the event of an asset sale it can be a good way of returning capital to shareholders. We also believe that if a cyclical company has managed to build up a strong balance sheet at the bottom of a cycle and there are no inorganic opportunities then a buy-back also makes a lot of sense. Sims Metal’s (ASX:SGM) buy-back in 2015 is an example of this.

We believe that there is an optimal capital structure which maximises the sustainable return on equity (ROE) of a company without putting the company at risk or taking away balance sheet optionality in the future, but it is more art than science.

However, we believe that a medium to longer term time frame needs to be considered, although there will always be shareholders and CEOs pushing for short-term sugar hits. Having a good understanding of the cyclicality of a business, were we are in the cycle, disruptive threats, contingent liabilities, operating leverage, financial leverage and other tail risks is extremely important when making the decision.

We are seeing increased buybacks across Australia and globally. The benefits of each buyback can be judged on a case by case basis, but in aggregate it is a little concerning that as stock market is making new highs every day, the number and size of buybacks increases.

In a recent interview to the Economic Club of New York, Stanley Druckenmiller eloquently broke down the numbers. He made the point that corporate debt has increased from $6 trillion in 2010 to $10 trillion today. Despite this, earnings have only increased by $500 billion in aggregate. Unfortunately, this increase in debt is not going towards innovation or growth capex, but rather buybacks.

“Over the period 2010 to 2018, buybacks rose from 20% of capital expenditure to 55%, with a much higher stock market… I was afraid that people were going to do stupid things and indeed they have”.

Anthony Aboud is Portfolio Manager at Perpetual Investments, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article was written for educational purposes and is not meant as a substitute for tailored financial advice.

The Perpetual Equity Investment Company Roadshow is coming to Sydney, Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth from 17 Oct - 8 Nov 2019. Register here.

For more articles and papers from Perpetual, please click here.