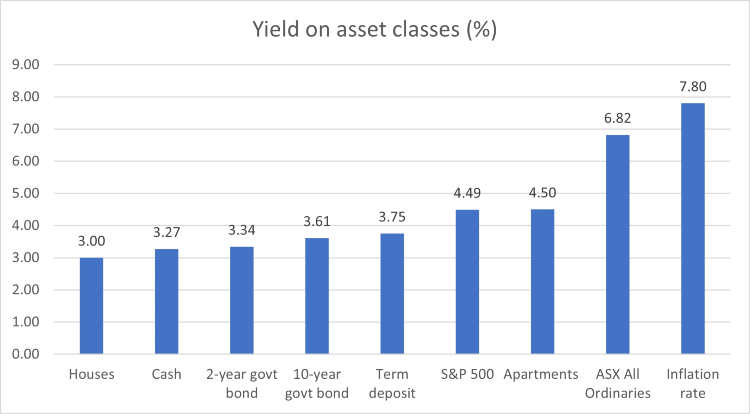

Here’s a chart of the current yields for the four key asset classes: cash, bonds, property and stocks.

Note: houses = avg rental yield across capital cities. Cash = bank bill index. Term deposit is CBA 12-month. Apartments = avg rental yield across capital cities. S&P 500 = earnings yield, trailing 12 months. ASX All Ordinaries = earnings yield, trailing 12 months.

You’ll quickly notice that the chart includes Australia’s current inflation rate of 7.8%. What the chart shows is that every major asset class isn’t earning enough to keep up with inflation. In real terms (inflation minus asset class yields), the yields are all underwater.

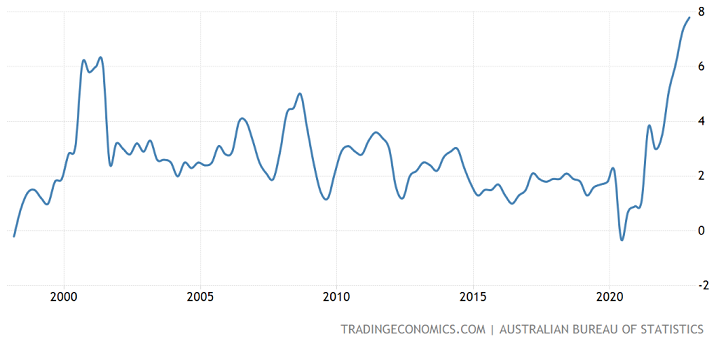

Australia inflation rate (% YoY)

That should tell you something, though: most people don’t expect inflation to stay where it is. Otherwise, the pricing and prospective returns of these asset classes wouldn’t make much sense. If inflation was to stay at these levels or rise in 2023, then the yields on all assets would need to rise too, and conversely, their prices would need to fall.

Given that inflation is expected to fall, then the next big question is: to what level? From the chart above, it’s reasonable to think that most markets expect inflation to drop back towards 3%. The reason I say this is that if inflation stays above 4%, the pricing for many assets would need to adjust and yields would have to rise.

The great inflation debate

Whether inflation falls to 3% or lower is the great debate in financial markets.

The majority of economists and central banks suggest that it will because broken supply chains during Covid caused the inflation spike, and therefore as these chains heal, inflation will fall.

There are others such as monetarist economists like Tim Congdon who argue excess money supply caused the inflation uplift, but that supply has fallen dramatically, and the risk is more of deflation than inflation this year.

There is another camp that suggests inflation will prove structural and stay high for some time. Global strategist, Russell Napier, suggests that governments rather than central banks control the levers of money creation now, and that means inflation will be here to stay. Financial commentator and author, Jim Grant, has some sympathy for a more recent school of thought arguing that inflation is a characteristic of politically weak societies – these societies tend to ovespend and are naturally expansionary.

Others in the ‘structural inflation’ camp such as author Edward Chancellor point to the long inflation and interest rate cycles of the past 200 years. In the US, bear markets in bonds (which mean rising interest rates and inflation) have lasted 30-40 years, albeit with a lot of volatility.

And then there are the commodity bulls who argue supply shortages in commodities, especially in oil, copper and lithium, are long-term problems, and that will lead to higher inflation. They believe there’s a perfect storm brewing for commodities, where supply will be limited due to environmental pressures on energy and mining companies not to produce, price caps and other governmnet intervention also disincentivising production, as well as reduced credit and equity availability to companies in this space.

Almighty cash

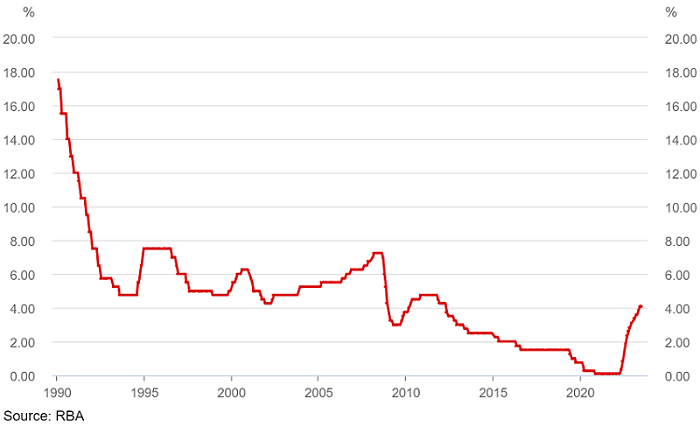

In 2022, cash outperformed most asset classes - thanks to the RBA lifting the cash rate from an all-time low of 0.1% to 3.35%. The RBA was late in responding to rising inflation and had to play catchup.

There’s been heated criticism of the RBA Governor after he reneged on a previous promise that rates were unlikely to rise until 2024. While that criticism is warranted, there’s been less attention paid to the decade prior where rates were kept extraordinarily low. When real rates (cash rates minus inflation) are kept negative for a long period of time, it’s no surprise that asset bubbles form, and then burst.

Cash is now yielding 3.27%, which appears bountiful compared with recent returns but remains low versus history. Markets are pricing in a peak cash rate of 3.9% in August this year. A cash rate at these levels will be welcome news for savers.

RBA cash rate (%)

Have bonds become ‘certificates of confiscation’ again?

Bonds have had quite the ride over the past three years. 10-year bond yields bottomed in March 2020 at just 0.6% before climbing to above 4.1% in July last year and easing back to 3.61% now. Recent falls reflect market expectations of decreasing inflation.

Institutional fund managers appear to be warming to bonds again, though I wonder whether this is a case of them appreciating getting some yield on their bonds, whereas previously there was almost none. Are bonds attractive on an absolute basis, or just compared with recent history?

To be fair, many of these managers are looking more at investment grade corporate bonds and high-yield bonds where yields of 5-8% are common.

The future performance of bonds will depend on the direction of interest rates and inflation. If inflation falls back to central bank targets of 2%, then bonds are attractive at current prices. If inflation proves stickier, then prices may have further to fall.

As noted above, bond bear markets tend to last 30-40 years. Zooming out from the short-term outlook, the bigger issue is whether a long-term bond bear market is upon us.

The ‘Australian dream’ or nightmare?

Australian residential property prices fell 5.3% in 2022. The largest falls were in Sydney (-12.1%) and Melbourne (-8.1%). Three capital cities saw prices rise: Adelaide +10.1%, Darwin +4.3%, and Perth +3.6%.

Prices fell on average because interest rates rose. The price reductions in residential property were relatively mild though and reflect the illiquidity of the asset class. Assets such as stocks quickly priced in the interest rate rises of 2022. More illiquid assets such as property, private equity, venture capital, and infrastructure have been slower to adjust to higher rates. That is still to play out.

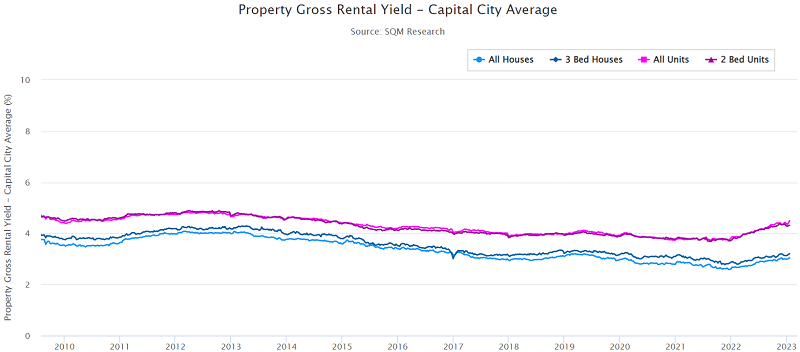

Put bluntly, current residential property prices make zero sense from a valuation standpoint, despite the recent correction. With risk-free 10-year government bonds yielding 3.5%, and many bank deposit and term rates above 4%, apartment and house price rental yields of 4.5% and 3% look mispriced. And that doesn't take into account the costs of owning a property - these are gross yields not net. Why invest in a risk asset such as property when you can earn as much, or more, in cash?

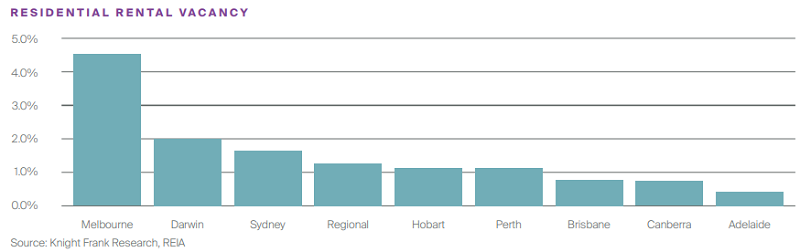

Bulls will argue that low rental vacancies mean continuing rises in rents, which will be supportive of property prices. And they have a point. The welcoming back of migrants, including skilled workers, should continue to boost rents this year.

Property bears will point to the avalanche of fixed-rate mortgages expiring this year, and the pain to come for households. About one-third of outstanding housing loans in Australia are on fixed rates, and of these, about two-thirds are due to expire in 2023. Mortgage rates for households with these loans will rise by 40% or more.

Further property price falls seem inevitable in the first half of this year, and beyond that, much will depend on whether interest rates peak at close to 4%, as current market pricing implies.

Commercial property: more pain to come

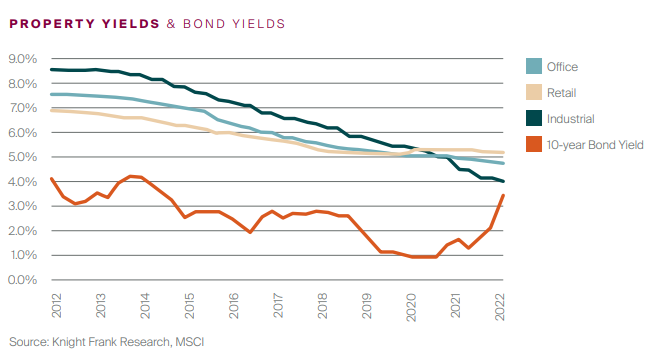

In the first chart in this article, I didn’t include commercial property yields, though I think they are worth discussing. If other illiquid assets have been slow to adjust to higher interest rates, then commercial property in Australia has been the tortoise!

The stock market has quickly priced in the adjustment, which is why many listed REITs are trading at 30-40% discounts to their net asset values. The market is saying that, ‘we don’t believe your asset valuations and they’ll need to come down to reflect the rate rises’.

While the prices of listed REITs have come down, physical commercial property hasn’t budged to the same degree. Industrial property in Australia yields close to 4%, while office and retail property yields hover closer to 5%.

Traditionally, investors command commercial property premiums above the 10-year government bond yield of 4-5%. With the 10-year yield at 3.61%, commercial property remains a long way from offering these traditional premiums.

It’s true that different segments have varied outlooks. Industrial property continues to benefit from the rise of e-commerce and build-out of warehouses to support it. Yet, that appears to be more than priced in.

As for office and retail property, the outlooks are challenging. Work-from-home is here to stay, and as office leases expire in coming years, it will put downward pressure on office rents and prices. Retail has only held up from a buoyant consumer which has benefited from government largesse during Covid. With higher mortgage rates, lower house prices, and the continuing move away from physical retail to online, retail property doesn’t appear to offer much value.

Aussie stocks: the global outperformer

Australian stocks outperformed most markets last year, with the ASX 200 falling just 1.08%. There was a wide disparity in returns between sectors, with energy and utilities up 49% and 30% respectively, while information technology got pummelled, down 34%.

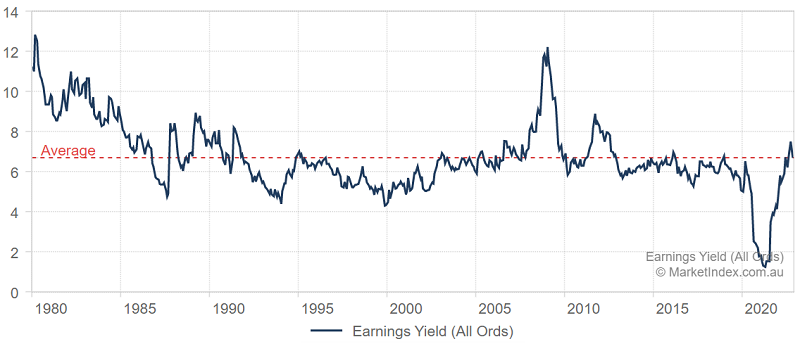

Where to from here? The All Ordinaries price-to-earnings ratio (PER) is 15x, and is close to its long-term average. The earnings yield on stocks of 6.8% compares to the 10-year government bond yield of 3.61% - which isn’t unreasonable.

The outlook for stocks will depend on earnings and the economy. Costs pressures will remain a major theme in the coming earnings season and for the remainder of the year. Higher interest rates, wages, and commodity prices (albeit some have come off in the past 6 months) will continue to pressure margins. And company sales will depend on how much rate hikes slow economic growth.

The good news is that company balance sheets are in good shape and dividend yields remain healthy, which should provide a buffer if there’s economic turbulence ahead.

US stocks: off to the races

After a dismal 2022, US stocks have come roaring back. The Nasdaq had its best January in 20 years. Large caps like Meta have more than doubled since November. Despite the FTX fiasco, Bitcoin has risen almost 50% from its low last year.

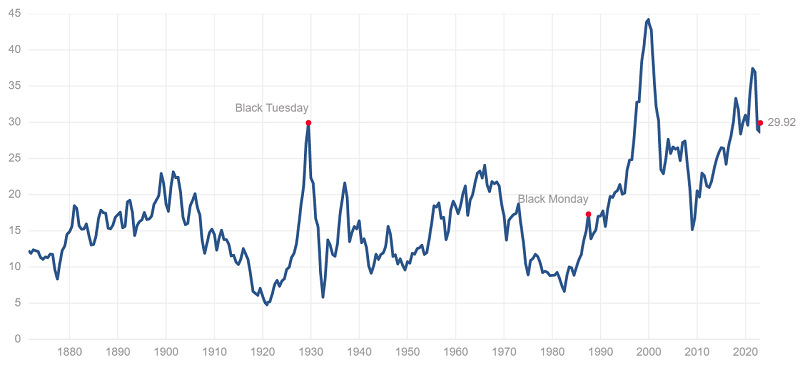

The S&P 500 is valued at 22x trailing earnings or an earnings yield of 4.49%. The PER is about 30% above its long-term mean and is clearly pricing in a peak in the Fed funds rate this year.

Long-term valuations appear more expensive. The Shiller PE ratio, which measures US stock prices versus earnings smoothed out over a 10-year period, shows the S&P 500 is valued at 29.9x. That ratio has only been higher in two periods: 1929 and the late 1990s.

Shiller PE ratio

Whether on a PER or Shiller PE basis, US stocks seem expensive despite last year’s correction.

James Gruber is an Assistant Editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.