Higher interest rates are political dynamite in Australia. That’s hardly surprising when 67% of households own homes, 57% of total wealth is in housing and household debt levels are amongst the highest in the world. Powerful real estate lobby groups and the governments and media beholden to them aren’t particularly happy about the prospect of more rate rises. Just ask RBA Governor, Philip Lowe, whose job is on the line because of it.

There’s barely a mention of the benefits of higher rates. People who’ve worked hard and saved money instead of taking on debt can now earn decent interest on their savings, asset bubbles in everything from stocks to real estate to crypto which caused all kinds of problems have popped, the gap between rich and poor has started to turn thanks to lower asset prices (the rich own these assets), wages are finally increasing, the scourge of inflation and higher prices are being targeted and loss-making businesses are dying after being kept alive for too long thanks to low rates.

That these points aren’t given much airtime highlights the often confused and one-side debate about interest rates. This article is an attempt to redress that and provide historical context to today’s situation.

The most important price in the world

Let’s first define what interest rates are. They are the price of money and arguably the most important price in the world. Everything in finance and the economy is based off them.

If you lend money to a bank, you expect to be paid for losing the use of your money. If you borrow money from a bank, you expect to have to pay for being able to access the money immediately. That’s why Edward Chancellor in his latest book on the history of interest rates, suggests rates are the ‘price of time’.

It’s ironic that though interest rates are central to capitalist societies, they aren’t determined by the free market. Instead, they are ‘fixed’ by central banks.

In Australia, the RBA determines the ‘cash rate’ and reviews the rate on the first Tuesday of each month except January. The cash rate is the rate used by the RBA for short-term lending and borrowing between banks. It’s a baseline for all interest rates in the market. A change in the cash rate by the RBA is significant because it signals the RBA’s views on the state of the economy. If the economy is too weak, the RBA will lower the cash rate to stimulate growth. And vice versa.

A brief history of interest

The conventional view of history books is that the barter trade system, where you swap one good or service for another, came before the arrival of loans and credit.[1] Yet newer evidence suggests that loans and interest have been with us from the beginning of time. Well before the advent of coined money in the eighth century BC, for instance.

About 5,000 years ago, Mesopotamians charged interest on loans, and this was before they had discovered how to put wheels on carts. We know this because they recorded their loans on clay tablets. These tablets reveal detailed loan arrangements, not too dissimilar to modern loan documents. They recorded names of debtors and creditors, loan amounts, dates, repayment due dates, interest charged, and the collateral attached to the loan.

The loans back then were most likely for corn and livestock – loaning farm animals, for example, and charging interest on that. The word ‘capital’ comes from the Latin word caput, meaning head of cattle. This prompted authors, Sydney Homer and Richard Sylla, to suggest interest originated from:

“…loans of seeds and of animals. These were loans for productive purposes. The seeds yielded an increase. At harvest time the seed could conveniently be returned with interest. Some part or all of the animal’s progeny could be returned with the animal. We shall never know but we can surmise that the concept of interest in its modern sense arose from just such productive loans.”

But it’s clear that loans proliferated on many things. And the reason is simple: capital was in short supply.

From the earliest days, interest on loans was required to induce people to lend their resources. Without this interest, they would have invariably hoarded their capital.

That’s why financial historian William Goetzmann suggests:

“The emergence of interest to incentivize lending is the most significant of all innovations in the history of finance.”

While innovative, interest and the moneylenders who profited from it have had their share of enemies from the start. English jurist and politician, Sir William Blackstone said in 1765, “When money is lent on a contract to receive … [there is] an increase by way of compensation for the use, which is generally called interest by those who think it lawful, and usury by those who do not”.

The Old Testament has several famous passages on usury:

“Thou shalt not lend thy brother money to usury, nor corn, nor any other thing.”

“If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor, that dwellth with thee, thou shalt not be hard upon them as an extortioner, nor oppress them with usuries.”

Indeed, the Hebrew word for usury is ‘to bite’.

Ancient philosophers also frowned upon interest being charged on loans. Aristotle described usury as immoral as ‘money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest’. And Plato depicted usury as setting rich lenders against poor borrowers.

In Ancient Athens, professional moneylenders had low social standing, and bankers weren’t popular either.

The ‘right’ interest rate

The necessity of interest has been an emotive debate from ancient times. So has the level of interest rates.

Some believe interest rates derive from the returns on real assets. Others see population growth and changes in national incomes as key drivers of rates. While many think market forces of supply and demand are at play.

A recent study by the Bank of International Settlements argues interest rates over the past 100 years has been influenced more by monetary regimes, such as the gold standard, Bretton Woods, and dollar standard, than by economic factors such as investment decisions.

There’s no consensus on the topic.

The raising or lowering of interest rates has drawn plenty of opinion at different stage of history. In the 1660s, England was struck by the Great Plague of London that killed 100,000 people, the Great Fire of London that gutted the city, and the financial extravagances of Charles II – which eventually resulted in a default of England’s sovereign debt.

A businessman, Joshua Child, had a solution to England’s woes. He proposed a decline in interest rates as ‘an abatement of interest would tend to the increase of trade and advance the value of the lands of England’. Child’s book, Brief Observations Concerning Trade and the Interest of Money, became one of the most popular books on economics during the 17th century.

Critics charged that a reduction in interest would only encourage money hoarding. And pamphleteers at the time pointed out that interest on capital was comparable to rent on land.

Later, the famous philosopher John Locke entered the debate with his book, Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money. Locke argued that lowering interest below its natural level would have many undesirable outcomes, including:

- Wealth would be redistributed from savers to borrowers

- Bankers would hoard money rather than lend it out

- Money circulation would decline, and prices would fall ie. deflation

- Too much borrowing would take place

- Asset price inflation would make the wealthy wealthier

- Lowering rates would fail to revive a spluttering economy

The ghost of John Locke after 2008

When the Global Financial Crisis hit in 2008, many central banks in the West cut their interest rates to close to zero. They also bought government bonds and other securities, otherwise known as quantitative easing. These measures were an attempt to revive economies that had been smashed by the biggest banking crisis since the 1930s.

After their economies had mostly recovered, they kept these emergency policies in place. In fact, interest rates were kept near zero for much of the period from 2008 to 2021. To put it into perspective, interest rates globally dropped to their lowest point ever. They were the lowest they’ve ever been in Australia too.

Never in history has there been such a sustained period of negative yielding bonds. At the peak in 2020, there were US$18 trillion in negative-yielding bonds. In February 2020, Louis Vuitton raised more than US$10 billion in bonds to finance its purchase of luxury jeweller Tiffany, some of which carried negative yields. In other words, some banks were paying Louis Vuitton interest on debt to finance its purchase of another company.

The extreme policies enacted by central banks resulted in outcomes that John Locke foresaw some 320 years ago. Low interest rates spurred soaring asset prices, rising inequality as the rich benefited from owning these assets, an explosion in borrowing, banks hoarding rather than lending money, and low inflation as money circulation slowed.

It took a pandemic and the mind-boggling printing of money in the US – with money supply increasing 25% year-on-year at one point – to bring about the economic revival that central bankers so desperately wanted. But it’s come with a predictable side effect: inflation peaking at high single digits.

Where we now sit

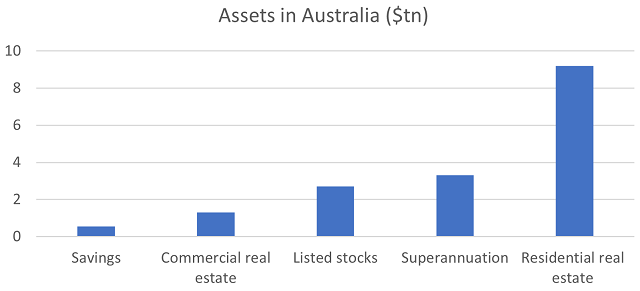

Australia finds itself in a difficult predicament. Australians have borrowed too much to buy homes. Rising interest rates will soon result in financial distress for many. And our economy is too reliant on housing. After all, the total value of residential property at $9.2 trillion dwarfs our annual GDP of $1.55 trillion. Crash the housing market and it’ll crash the economy. Therefore, rates can’t go too high.

But then there’s inflation. Letting inflation run is dangerous. Many countries and civilisations have fallen because of rampant inflation and the devaluation of their currencies.

Getting the level of interest rates right will be a treacherous balancing act. And it’s unlikely to be solved by installing a new RBA Governor and pressuring them to lower rates.

Yet it needn’t have come to this had Australian and other central banks pursued more orthodox economic policies up to 2021.

How it plays out from here may well be one for the history books.

[1] Much of this history has been sourced from Edward Chancellor’s book, The Price of Time.

James Gruber is an Assistant Editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.