The number one rule of investing is to generate a return above inflation, after taxes. Over the long turn, taking on higher risk premia tends to result in higher returns, which helps in achieving this goal. Over the past 30 years, equities generally outperformed bonds, bonds outperformed cash and all three outperformed inflation.

However, many investors do not have a 30-year time horizon and 2022 reminded us that there can be periods wherein nothing outperforms inflation. It’s during these times that investors may benefit from focusing on the direction of interest rates and looking to valuations to determine where to allocate over the medium term. With the repricing of bond yields, there are now reasonable alternatives to equities, but is it too early to allocate to sovereign bonds? Below we discuss the current macro environment over the coming months and which asset classes are showing attractive valuations, to help investors navigate where to consider investing money today.

All eyes on the US consumer

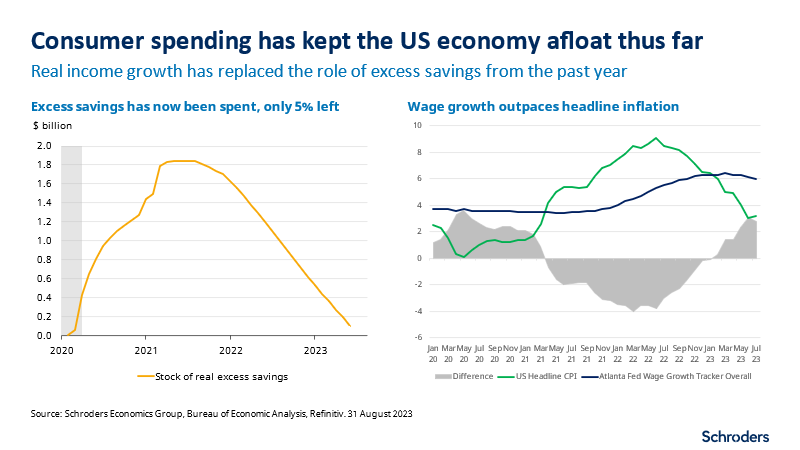

The US consumer has been more resilient than expected in the face of an aggressive interest rate tightening cycle. Unlike in Australia, rising interest rates do not translate to immediately higher mortgage payments, given the majority of home loans are fixed rate, so most of the pain to US consumers was from price inflation from 2022 onwards. Thanks to COVID-19 stimulus payments, US households were able to accumulate US$1.8 billion in excess savings, which helped provide a buffer to these increases in prices rather than relying solely on their wages to make ends meet.

Today these excess savings are mostly depleted, removing an important safety net to households. We have also seen debt levels rise, such as credit card debt per household reaching new heights, and deferred repayment programs ending, such as the moratorium on student loan payments, which points to consumers becoming stretched in the coming months.

However, consumers are now supported by real wage growth, which was absent last year. US households saw strong nominal wage gains in 2022, but these were more than offset by sky-high inflation. Headline inflation (the type of inflation that includes energy prices and the inflation measure that most consumers care about) has more than halved since its peak. This has meant real wage growth has gone from being deeply negative in 2022 to being strongly positive in 2023. Wage growth is rolling over but at a slower pace than inflation, meaning consumers have another few months of strong real wage growth, which will continue to support consumption. That is, as long as workers can keep their jobs.

Easing in the labour market

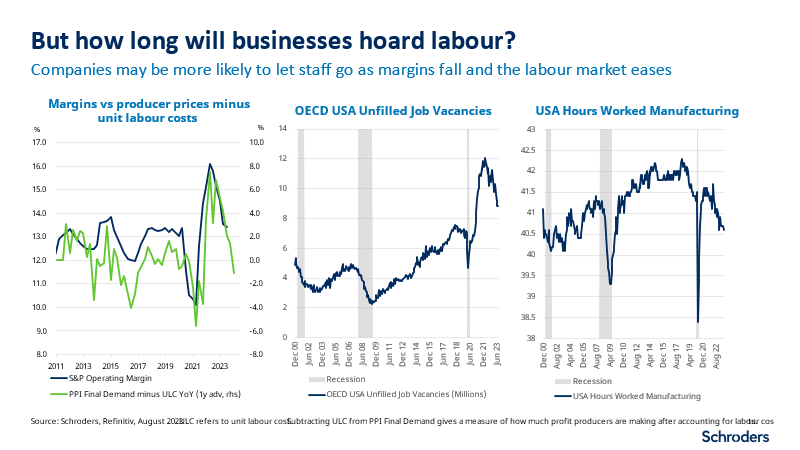

The labour market has been incredibly tight since economies reopened after COVID-19. Companies struggled to find workers to meet the surprise increase in demand from consumers and they are now reluctant to let these workers go, even as demand cools. Small businesses employ 48% of the US workforce, but the NFIB survey of small businesses shows that it’s the worst time to expand since 1980, other than the low experienced in 2009. Hours worked in US manufacturing continues to fall, consistent with companies who are holding on to employee labour but have less work to give them. This doesn’t suggest a strong case for businesses to continue holding onto excess labour, especially as it starts to eat into profit margins.

With margins expected to roll over as unit labour costs rise above producer prices (PPI final demand), there is a strong case to shed labour. The recent fall in both unfilled job vacancies and the US quit rate (a high quit rate implies employees are confident they can find a new job easily) could perhaps signal to small businesses that it’s now safe to downsize their workforce, which will place upward pressure on unemployment.

US equity valuations look stretched

For these reasons, we remain more wary of the US economy looking forward. Our recession models are still suggesting a high probability of recession in the coming few months. This is in stark contrast to the market, which is still pricing in a soft landing, where growth holds up but the Federal Reserve can cut interest rates as inflation falls under its own weight.

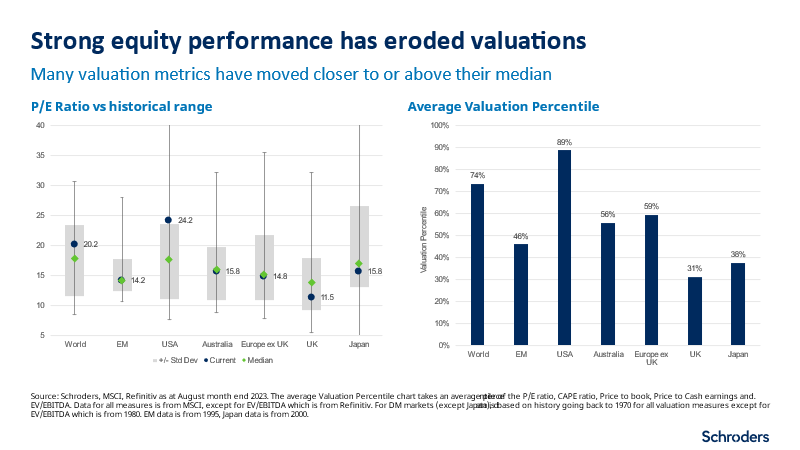

The recent 28% rally of the S&P 500 off the September 2022 lows has pushed the trailing Price to Earnings (P/E) ratio up to over 24x, which is expensive relative to its own history and when compared to other major regions. Forward looking P/Es are more reasonable at 17x, however this assumes earnings growth in 2024 of 12%, which seems ambitious, especially when the majority of this comes from expectations of margins expanding, which is contrary to what we discussed above. When averaging five different valuation metrics, the US is in the 89th percentile expensive, which has dragged the global equity valuation up to the 74th percentile. Typically, this does not bode well for longer-term forward-looking returns.

That said, while a case can be made for being underweight equities overall, valuations are fairer in other markets such as Australia, where valuations are around or below the 50th percentile. Simply looking at valuations, investors would favour Australian over global equities, and within global equities favour cheaper markets like Japan over the US.

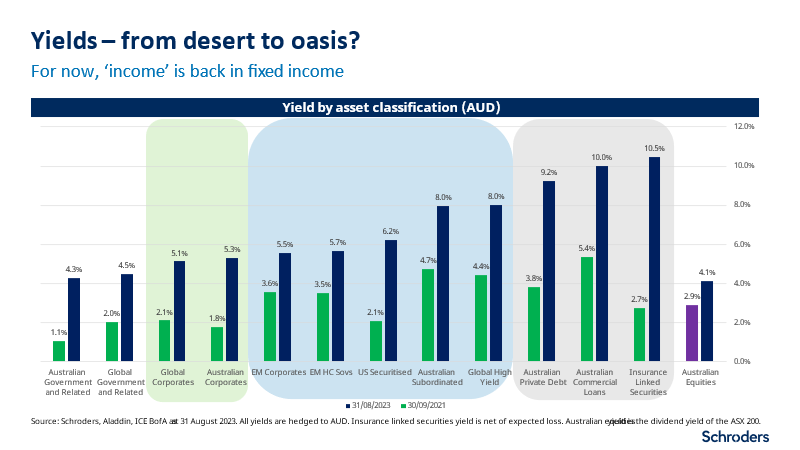

For now, the income is back in fixed income

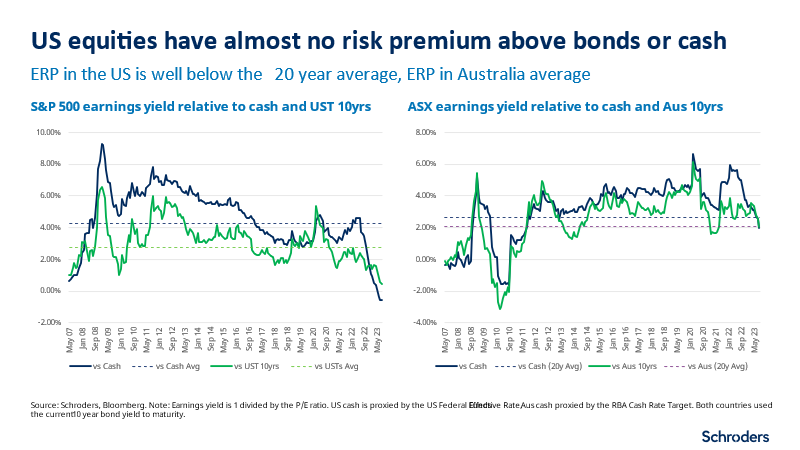

It may feel strange after over a decade of near zero interest rates, but fixed income is now offering attractive yields. 10-year government bonds in Australia and the US, along with the RBA cash rate, now yield over 4%. That is the same yield that was on offer from US high yield corporates (aka junk bonds) throughout all of 2021. After over a decade of there being no alternative to equities, investors now must decide the relative attractiveness between equities and fixed income.

One way to determine the relative attractiveness of equities is to calculate the Equity Risk Premia (ERP), which is to compare the earnings yield of an equity market (the inverse of the P/E ratio), to the yield on offer from either government bonds or cash. Based on this metric, the ERP for the Australian market is around 2% above both bonds and cash, which is around its 20-year average. However, US equities have seen their ERP collapse to the lowest levels in 20 years. This means an investor really has to think about whether US equities are a better investment than government bonds, or even whether they would be better off in cash.

Our cash rate models suggest we are approaching the end of the tightening cycle, which is typically the best time to add duration (buy longer dated government bonds). These models suggest cash rates should be around 4% in both the US and Australia, which is at or below current policy rates. However, we still believe it is too early to add duration, given the uncertainty over inflation and growth. Longer dated government bond yields in the US still look too low, given the level of inflation and growth expected in the US economy.

Our model for 10-year government bonds suggests Australian and US bond yields are close to fair value. Therefore, while investors would typically like to add more duration as the economy slows, adding too early will be painful. For now, the front end of sovereign curves (less than 5-year maturities) and cash looks like a more suitable place to hide, until we get more confirmation economies are rolling over.

Let carry do the heavy lifting

The above suggests the market could be quite choppy as equity valuations come under pressure and government bonds plateau. In the meantime, investors may benefit from investing in high quality fixed interest investments that offer higher yields than government bonds (known as carry).

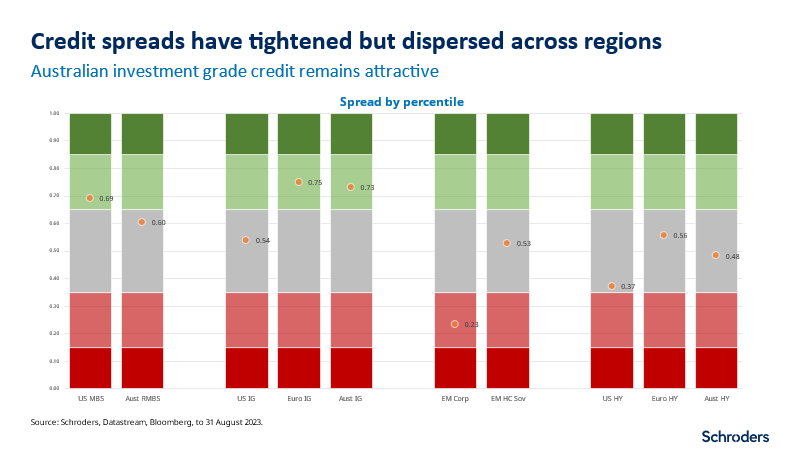

Corporate credit is typically lower duration than sovereign bonds and therefore has less interest rate risk, while also providing extra yield (spread above sovereign bonds of the same duration) to compensate for credit risk. Current yields in credit securities are between 5% and 8%, providing a healthy pick up above cash or sovereign bonds. Investors can use managed funds to access a globally diversified portfolio of credit securities. Valuations are more attractive in investment grade credit, where spreads are between 50-75th percentile cheap, whereas higher risk non-investment grade credit spreads are more expensive in the 35-50th percentile.

Moreover, the credit spread in investment grade is enough to break even if we see a default cycle similar to those seen in past recessions, whereas high yield is only compensating investors for a standard mid-cycle default regime. This seems complacent, given the increase in defaults this year and tightening lending standards, which historically would lead to much wider high yield spreads. Australian investment grade looks particularly attractive, with spreads wide relative to history and compared to global credit and is also compensating investors for a default cycle worse than a recession.

Alternatives are an alternative

While high yield corporate bonds may not be providing adequate compensation for risk, that doesn’t mean there aren’t attractive high yielding assets. Looking broader and widening the opportunity set allows investors to find assets that have high total yield, low interest rate risk and provide diversification to portfolios.

For example, banks have stepped away from lending in certain areas of the market, causing yields to rise to attract investors to take their place. A collection of US securitised credit offers over 6% in Australian dollar (AUD) terms, that’s more than Emerging Market sovereign Debt (EMD), but has a credit rating of A- versus BBB- and zero duration risk versus 6.7 years for EMD. Fixed rate Australian commercial loans are currently offering around 10% yield, but with less than 1-year duration, and floating rate Australian private debt offers AUD cash +5-6% (currently yielding over 9%) but with no interest rate sensitivity. These offer potential for strong yield to investors and more adequately compensating for credit risk, without taking on interest rate risk, albeit taking on liquidity risk.

When sovereign bonds are no longer providing diversification, other assets need to be considered. For example, insurance linked securities pay high yields but can lose money during catastrophic weather events, such as hurricanes. These assets have next to zero correlation to equities or bonds as they are unrelated to the economic cycle and instead driven by the weather. They are currently yielding over 13% or 10% in AUD terms once expected loss is removed but have negligible interest rate risk with duration less than 1-year. There are plenty of places to invest even when equities or bonds look unattractive, but it requires investors to look broader and deeper to find interesting opportunities.

So where are the opportunities?

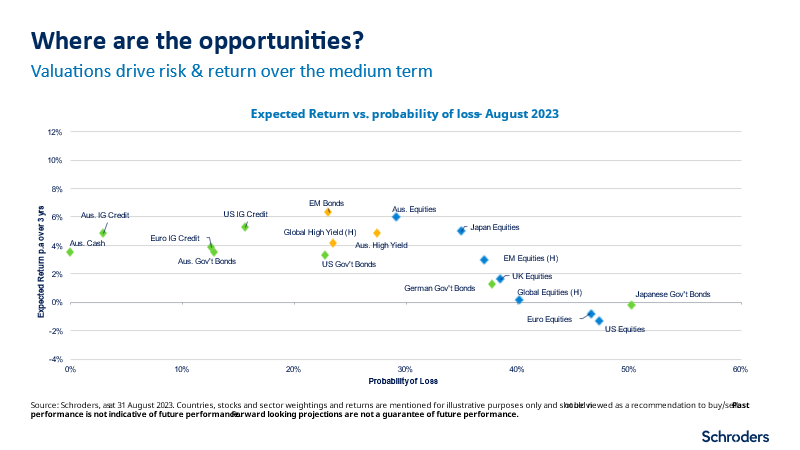

Pulling this all together, where do we see the opportunities for investment? The above would suggest being cautious on equities, especially US equities, but favouring countries like Australia and Japan. While duration may be an attractive buy soon, we believe that short term volatility will likely remain high, favouring cash in the interim. While we wait for equity risk premia to rebuild to more attractive levels, taking carry in credit helps deliver consistent returns in the meantime. Investment grade credit (and in particular Australian credit) along with select higher yielding alternative credit looks attractive.

A similar picture is evident below, where we plot valuation adjusted forward looking 3-year returns versus their probability of loss. Most assets are offering similar levels of return today, but with very different levels of risk, so holding high levels of equities is not rewarded. Investors may consider taking the carry in credit instead. Cash may be used as a safety net while looking to add to duration as we approach the end of the year, and the economic slowdown may become more pronounced. Then, when valuations adjust and expected returns for equities migrate into the top left quadrant below, investors may consider re-setting their asset allocation back to favouring equities and go back to focusing on harvesting that risk premium for the long run. But we’re not there yet.

Sebastian is the Head of Multi-Asset for the Australian Multi-Asset team and co-portfolio manager of the Schroder Real Return Fund strategies and the Global Total Return Fund. Schroders is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This document is issued by Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 22 000 443 274, AFSL 226473) (Schroders). This document does not contain and should not be taken as containing any financial product advice or financial product recommendations. It does not take into consideration your objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.