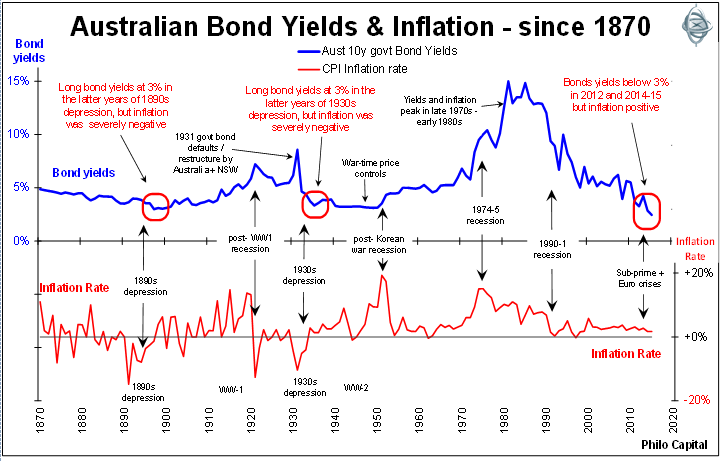

Australian government bonds are trading at extraordinary high prices and low yields. The only times yields were anywhere near this low were in the 1930s depression and in the 1890s depression, but in both of those depressions inflation rates were severely negative (deflation). Today, inflation is positive.

Unless you believe Australia is heading for another depression in the next 10 years, bonds appear over-priced at current levels. Yields may fall even further due to the weight of foreign money, but real returns for bond holders are likely to be very poor over the medium to long term from current levels.

Although the cash rate in Australia is at record lows, yields all across the curve up to 10 years are even lower, down to as low as 2% for 1 to 5 year terms. Even 20 year bonds are yielding less than 3%. Australian inflation-linked bonds are now trading at such high prices and such low yields that they imply inflation will average just 2% per year for the next 10 years. Again, these are depression-type levels. The most obvious conclusion is that the ‘safest of all assets’ in Australia – inflation-linked government bonds with very little risk of default – are in a speculative bubble like other ‘risky’ assets.

Thanks to the declining yields, recent returns from bonds have been good. However, even with yields at such low levels, they are still attractive to global investors. Foreign investors look at yields in countries like Canada, a similar market to Australia, and see yields on Australian bonds are more than 1% higher than on Canadian bonds. The only government bonds trading at higher spreads are in Greece, as it lurches toward another likely default. Unlike any era in the past, foreign investors now own the bulk of Australian bonds on issue and the flood of foreign yield-chasing funds is likely to continue to keep yields low for some time yet.

This cycle is usually halted only by a sudden currency collapse which turns the inward flood of speculative money into a rapid race for the exits. Sometimes these turnarounds are triggered by external crises, like the Russian default in 1998, and at other times triggered by domestic crises, like the current account crisis in 1986. This time the trigger for a sudden turnaround may be a Russian default once again, or it could be the worsening federal budget crisis (along with the Liberal party chaos and the volatile Senate), which is starting to seriously alarm many foreign investors.

In the current environment the catalyst for a sell-off in the AUD and bonds will most likely come from an external source, with many economies and geopolitical situations balancing on a knife-edge. Many investment markets are hovering at over-priced levels, supported only by central bank money-printing.

Ashley Owen is Joint CEO of Philo Capital Advisers and a director and adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund. This article is for general educational purposes and is not personal financial advice.