Markets move in cycles. The last 40 years have seen interest rates down from 20% to less than 1%, quietly fuelling a rise in bond returns over the same time. This has driven the return of the typical 60/40 portfolio (60% stocks and 40% government bonds).

Over the 40 years, the benefit of the 60/40 portfolio has been that when economic growth has slowed:

- stock prices have been weak

- but interest rates have fallen, increasing the return on bonds

And vice versa for when economic growth has improved.

With interest rates at almost zero, there is a reasonable argument that this trade is over for the current cycle. I'm quite partial to that argument for Europe and Japan.

But for Australia, I'm expecting one last hurrah before the end of the cycle.

A bond Armageddon?

Government (as opposed to corporate) bonds are typically a low-risk investment. However, there are plenty of doomsayers for the government bond market calling for a bond Armageddon with 10-year bonds losing 35% with a return to ‘normal’ interest rates.

And the doomsayers are (technically) correct that if 10-year government bonds rose from the current level of below 1% to a more typical 6% then the ten-year bond price would fall 35%. But this is grossly misleading as to the true risk to investors (rather than traders) for four reasons:

Reason 1: The speed of adjustment is key

The -35% price movement in 10-year bond prices is only true if it happens overnight.

A bond ladder is a more typical exposure for investors. Those who invest directly or (like our clients) through a separately managed account have far less to fear.

An example bond ladder might have one bond expiring every year for the next 15 years. Each year, your bonds move one year closer to maturing. Each year you take the money from the bond that matures and buy another 15-year bond.

If bond yields move evenly from current levels to 6% over 10 years, then bond investors with this strategy will make a profit. Not a great profit admittedly, only about 0.5% p.a. – but a long way away from a 35% loss.

If the increase in interest rates was faster, say five years, then you would make a loss (if you sold the entire portfolio in five years) of about 2.5% p.a. Not a good outcome. But not a shocking risk.

Reason 2: 10-year bonds are a trading strategy, not an investment

Ten-year bonds are not really an investment. You can buy a 10-year bond, but in one year you no longer own a 10-year bond: you own a nine-year bond.

To keep a 10-year bond, you need to sell your 9.75-year bond and buy a 10.25-year bond, then wait six months and do the same thing again. And again. And again. 17 more times.

This is the action of a trader, not an investor.

The effect on investors, who tend to have a range of different maturities, especially in a 60/40 portfolio is significantly different from a trader.

Reason 3: Traders take risks on bonds, investors get certainty

Traders who buy and sell rapidly, or who use leverage, or who take long/short positions have reasons to worry about significant losses on bonds.

Typical investors, though, buy bonds because of the certainty they provide.

When you buy a current Australian 10-year bond, you know exactly the return you will get if you hold it to maturity. You will pay $115 today for the bond, you will get $1.25 every six months, and in May 2030 you will get back your $100. You have locked this return in.

The price of your bond will vary. But for an investor who is holding to maturity, the returns do not change.

Reason 4: Inflation

Most bond doomsayers that are calling for the Armageddon are doing so because they are forecasting the imminent return of inflation.

One day they will be right. But the developed world has spent the last ten years (20 years in Japan), trying to create inflation. And failed.

Now the world is staring down the largest unemployment shock since the great depression. Household and corporate debt levels are already elevated - it will be difficult and increasingly dangerous to increase them from current levels.

Inflation is the most significant risk facing any bond holding. But it is not a risk right now.

My view is that a mix of increasing inequality and central bank rules make it very difficult for monetary policy to create inflation. Inflation, when it finally comes will be a reversal of inequality and massive stimulatory government spending. The government spending we are seeing at the moment is to reduce the depths of the recession, it is not (yet) the type of spending that increases inflation.

What is the last hurrah?

The real benefit of bonds is that you know already how much money you are going to lose over 10 years if you hold to maturity. The answer is zero. If you buy a 10-year bond at 0.9% and hold it to maturity, you will get 0.9%.

That is the point. Bonds give you certainty of return. What they also give you is the option to sell the bond part of the way through to take advantage if yields continue to fall.

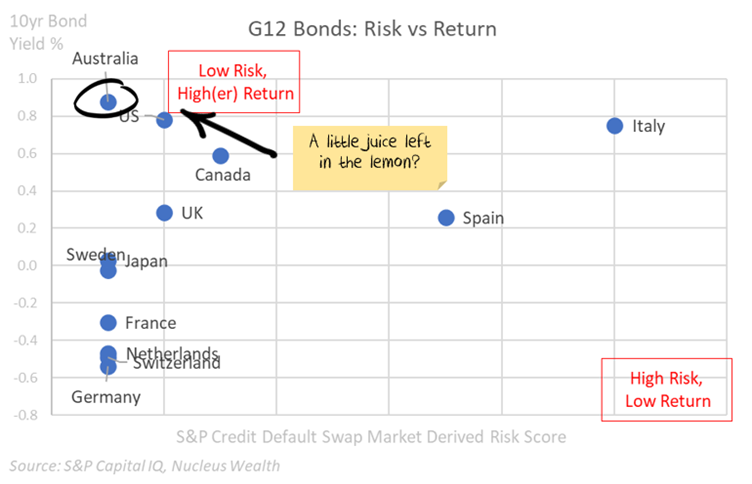

At the moment, Australian bonds are among the highest in the developed world where credit risks are low:

If Australian bond yields chase the rest of world bond yields lower, and we expect they will, the value of a typical bond ladder will increase 5-10%. As I've noted above, that only matters if you sell the bonds though.

In our portfolios, we do expect to sell these bonds and switch into equities at some stage.

Going forward, the risk-return equation for bonds is broadly:

- 5-10% p.a. upside if we are right and economic conditions worsen.

- 5% p.a. losses if we are dramatically wrong.

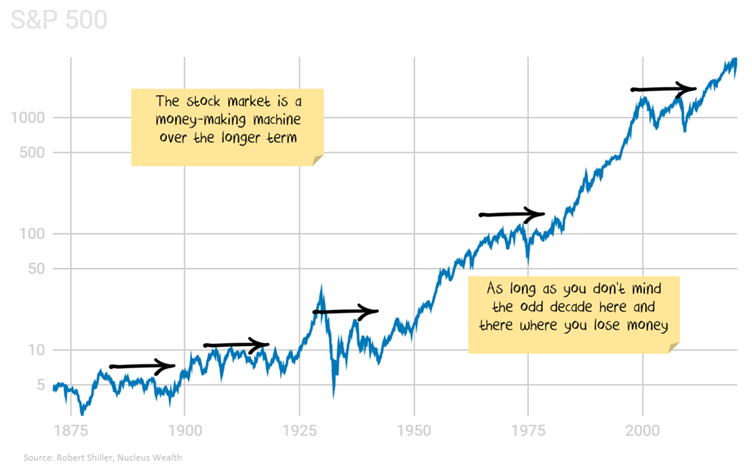

What about a ‘set and forget’ 60/40 portfolio?

Here is the difficult part. If you are buying and holding, then your bonds are not going to give you much of a return. Plus, stock markets are trading at valuation levels that are as expensive as they have ever been.

I don't mind the outlook for the world economy once we get deeper into the 2020s - but more on that another day.

It is possible that markets will continue to hope for better profits for several years until the profits finally justify today's prices. Basically, a sideways move for years.

Based on current valuations, buy and hold is unlikely to be a winning strategy. Within our superannuation and investment funds, we are expecting to need to be considerably more nimble than a set and forget 60/40 portfolio to achieve reasonable returns.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.