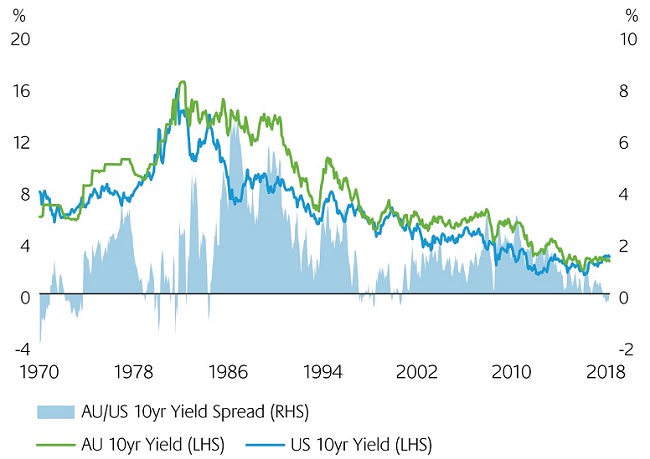

Australian sovereign bond yields have typically traded above many global counterparts, particularly those in the US. This has reflected a number of fundamental factors, including Australia’s higher long-term average economic growth and inflation. Australia's inflation target of between 2.0% and 3.0% per annum is slightly higher than the Federal Reserve's 2.0%. Higher Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) yields have also arguably reflected Australia’s higher term premium, given the economy is relatively small and largely influenced by commodity exports.

A reversal of historical norms

Accordingly, the Australian economy can be susceptible to fluctuating fortunes. The current desynchronised global growth environment, in which the Australian economy is lagging the US, has seen a reversal in this historical relativity. The spread between Australian and US 10-year sovereign bond yields has moved materially into negative territory for the first time in over 30 years, although CGS spreads relative to German bunds, UK gilts and Japanese government bonds are little changed this year. This raises questions over the sustainability of this negative spread and, in turn, whether it might affect offshore demand for Australian bonds in the future.

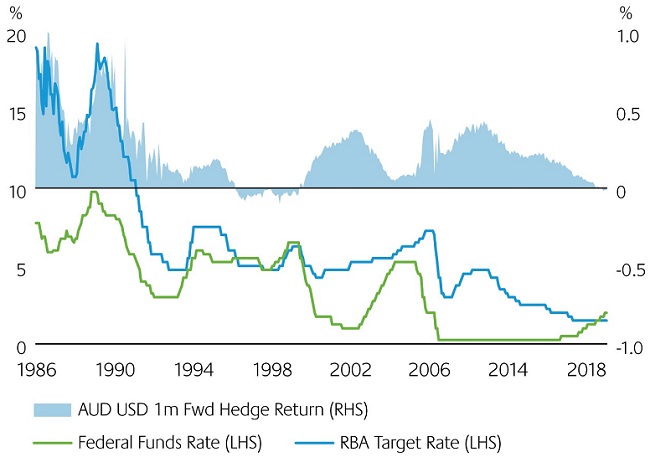

An additional issue is the impact of front end interest rate differentials on hedged returns. Historically, hedged exposures have been the norm, but in a world of negative returns from hedging, this default setting needs revisiting.

The sustainability of negative Australian versus US spreads

From a fundamental economic perspective, most would argue that equilibrium interest rates in Australia should be somewhat higher than those in the major G3 countries. A medium-term view of the key drivers of 10-year yields – potential growth, long run inflation outcomes, and term premia – are all consistent with higher yields locally. Consider:

- Australia’s population growth rate (through both natural increases and immigration) remains higher than in the US.

- Productivity has been higher in Australia than the US historically, and while this is less certain going forward, the balance of risks remains skewed towards higher Australian outcomes.

- The inflation target is higher than in the US, Europe and Japan.

- As a small open economy, Australia is subject to volatility in domestic and external demand so term premia should be structurally higher for Australia than other markets.

Notwithstanding, Australia’s sustained economic prosperity and credit rating stability has historically supported demand for Australian paper, particularly against a background of sub-par economic outcomes, deteriorating fiscal positions and declining credit quality globally. Indeed, Australian CGS have become a core diversifying holding for many central banks, sovereign wealth funds and other large institutional investors worldwide. The case for diversifying into Australia in such an environment is a logical one from a default risk perspective, and makes even more sense when there’s also a clear return benefit in making the allocation.

Although the return advantage of Australian bonds has been removed, the diversification benefits remain, particularly when considered against Japanese and European alternatives. We believe demand for Australian paper will persist, potentially allowing local yields to trade below comparable US Treasuries for sustained periods of time, albeit with an average ‘over the cycle’ profile that continues to show a positive spread relative to the US.

Short end differentials and implications for hedging

Front end (cash and money market) rates have also recently fallen below their US equivalents. With the Federal Reserve committed to a path of monetary policy tightening while the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is expected to keep local rates unchanged for an extended period, this differential could widen further and persist for an extended period of time.

This environment represents a different dynamic from a hedging perspective for AUD-based global fixed income investors. Historically, hedging global fixed income exposures back to AUD provided a higher yield and lower volatility in total returns. However, there is now a distinct trade-off between return and volatility, on at least part of the portfolio.

Hedging policy considerations must factor in expected total returns of a hedged exposure, as well as the hedging costs themselves. We believe Australian investors will continue to favour hedged offshore exposures due to:

- The diversity benefit that global fixed income provides, and

- The continued positive hedge benefits from the non-US elements of these exposures.

Where specific US-only exposures are included, hedging appears likely to remain the default option to help mitigate the potential portfolio impact of currency volatility. Overarching currency views, as well as a focus on the forces that may influence them beyond interest rate differentials, will undoubtedly continue to drive hedging decisions.

Could persistent negative spreads have long-term implications for Australia?

We do not believe negative spreads alone will have any significant adverse impacts on Australia, or on the domestic bond market in general. Supported by AAA ratings, lower rates are favourable for the Commonwealth Government and state issuers from a cost perspective. They also reflect confidence among the international investment community in Australia’s long-term economic prospects. Lower rates might also be expected to be supportive of domestic economic activity and should make it more comfortable to fund current account deficits.

Perhaps a more interesting question is whether the RBA could miss out on participating in a global rate hiking cycle altogether and, in turn, what risks this might present over time.

The RBA continues to suggest the next move in domestic rates will be upward. But with inflationary forces under control and with lenders increasing variable mortgage rates independently of moves in official policy, we are unlikely to see a rate hike in Australia in the foreseeable future, potentially not until 2020. There’s some risk that the global interest rate cycle will have turned before domestic conditions justify an increase in Australia and the RBA could therefore miss an entire hiking cycle globally. If that were the case, with local rates staying lower for longer, current policy settings would increasingly be perceived as the norm by both fixed income investors and Australian households. In turn, this would potentially increase the vulnerability of the local economy to future rate increases, as businesses and households had structured their activity and spending based on current settings.

A balanced risk approach

Relative yield differentials and duration positioning are by no means the only drivers of performance in our fixed income strategies. To varying extents, our Australian and global fixed income portfolios maintain exposure to a wide range of alpha sources globally. Australian and US signals including rates, curve, country spreads and FX are just a subset of the return sources that are utilised globally. The ‘balanced risk’ approach employed in the management of all portfolios ensures they are constructed in a diversified manner. No individual risk position or view has the ability to dominate the return profile, increasing the likelihood of accomplishing portfolio objectives and providing investors with better risk-adjusted returns over time.

Stephen Cooper is the Head of Australian Fixed Income at Colonial First State Global Asset Management, a sponsor of Cuffelinks. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.

For more articles and papers from CFSGAM, please click here.