Part 1 of this story discussed government debt, both domestic and foreign, and the various ways in which governments can avoid repaying their debts in full, through default, restructure and/or inflation. We also looked at the extraordinarily high levels of Australian government debt in the early 1930s compared to the debt levels of countries in the current government debt crisis.

In Part 2, we look at how Australia’s government debt default and restructure occurred, which bond holders were rescued, and which took a ‘haircut’ on their interest and principal repayments and had to wait decades to get their money back.

Inflation was not an option

For most countries, the easiest way to reduce the real debt burden is via inflation – to repay debts with paper money that is less valuable in terms of its real purchasing power.

Inflation was not an option for Australia in the 1930s depression. Australia was crippled by price deflation as global commodity prices collapsed by up to 50% and more, and unemployment soared to 30%. The government was unable to create inflation despite abandoning the gold standard in January 1930 and devaluing the Australian pound progressively through 1930 and 1931. Instead of inflation reducing the real size of debt and interest payments, price deflation did the opposite. It increased the real cost of interest payments and the real size of debts.

The government had already cut wages by 10% in May 1931 and also cut pension payments to save money, and additional cuts were unlikely to be palatable or politically feasible.

On 1 December 1930 and again in April 1931, the government’s wholly owned Commonwealth Bank very pointedly and publicly refused to lend it more money to finance the government deficit or infrastructure spending. (The Commonwealth Bank carried out some central banking roles prior to the establishment of the Reserve Bank of Australia in 1959. The Commonwealth Bank’s 1930 refusal was the first step down the long road toward the independence of central banking in Australia).

On 30 April 1931 the NSW government defaulted on interest payments due in London. Then on 30 June the Commonwealth government’s account in London had run out of money and the Bank of England had to make an emergency bail-out loan so that Australia could pay maturing treasury bills on the London market. With more payments due in August, the government had to decide who not to pay.

Who do you rescue - your own citizens or foreign bankers?

There was no way out for the government. Tax revenues were falling, welfare costs were rising, foreign debt markets had closed their doors on Australia, local domestic savings were drying up, banks wouldn't lend to the government and even the Commonwealth Bank refused to lend it more money. Something had to give. Interest payments were falling due and maturing debt needed to be repaid or refinanced.

In the end, the government decided that Australian domestic bond holders should suffer losses to ensure that the London bankers were paid in full on the foreign debt owed in pounds sterling. This was an extremely controversial and hotly debated topic at the time. With local unemployment rates running at 30% and wages and pension already cut, the government decided that ordinary ‘mum and dad’ bond holders should suffer even more losses so that ‘greedy’ London bankers would get paid in full!

There were several reasons for this decision. The first was a widespread and deeply held sense of national pride - to restore our international reputation, and to restore Australia’s credibility and ability to borrow on international markets.

As it was so controversial, a national referendum was held on the issue. 97% of domestic bond holders who voted in the referendum effectively volunteered to take a loss on their bond holdings so that the foreign creditors wouldn’t suffer any losses, for the good of the country and its international reputation. This was most unusual. Usually countries choose to repay their own citizens in full and let foreign creditors take a loss.

A second reason was that it was our duty as a loyal colony to do everything we could to repay our debts owed to the mother country, just as it was our colonial duty to send our troops off to help Britain in the two World Wars.

A third reason was that the government policy was effectively being run by the London bankers, in Sir Otto Neimeyer, the Bank of England’s representative sent to clean up our finances, and the Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank, Sir Robert Gibson, whose policies reflected those of the London bankers.

The lesson is that if most of a government’s debt is owned by foreigners, then foreigners control the agenda. Japan today has astronomical levels of debt – similar to Australia in the 1930s - but at least it controls its own agenda because almost all of its debt is owned internally by Japanese government departments, pension funds and individuals.

In contrast, most of the US government’s debt is owned by foreigners (as is half of Australia’s current debts), led by China, and so the US runs the risk of losing control of the agenda if and when its debt problems escalate to crisis levels. In the 1980s we saw escalating nationalist trade and currency disputes between Reagan and Nakasone when the US became the world’s biggest debtor nation with Japan controlling the debt, and we are seeing similar trade and currency tensions escalating today between the US and China.

Australia’s debt restructure ‘haircut’ deal

Following the successful national referendum, the Commonwealth legislated to mandate a Greek-style debt restructure deal in which all domestic (Australian) holders of government debt took a ‘haircut’ on their bond holdings. Interest on all bonds was reduced by 22.5% and repayment of principal was delayed for up to 30 years.

The big default occurred on 31 December 1931 when the Commonwealth defaulted on (failed to pay) interest and maturing principal on all of its domestic bonds. The compulsory Conversion Bill did not become law until January 1932 after it was ratified by the States.

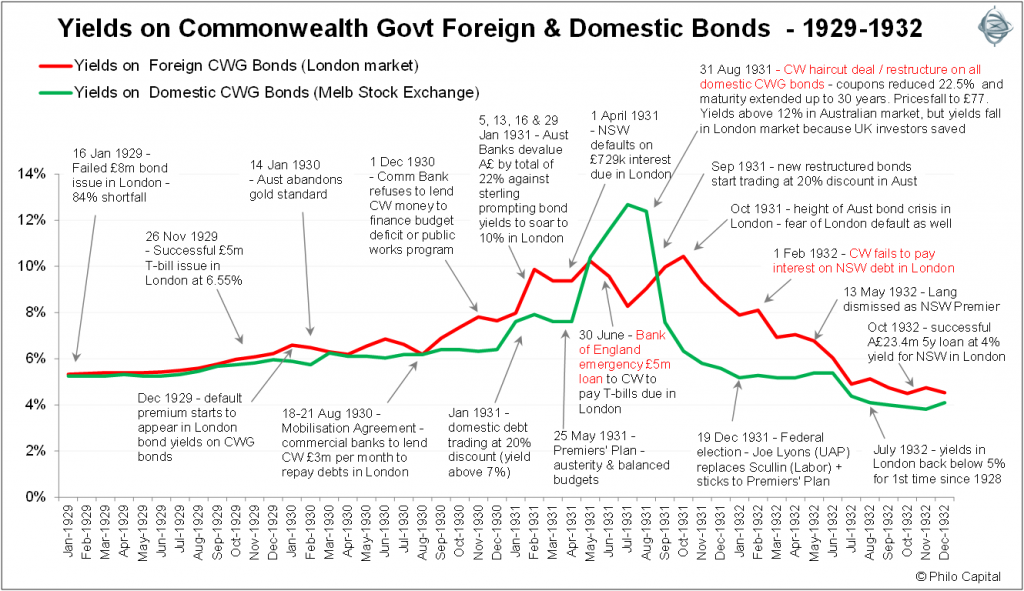

The following chart tells the story through bond yields. It shows market yields on Australia’s long term bonds between 1929 and 1932, together with the key events leading up to, during, and following the haircut restructure. The green line shows market yields on domestic (Australian pound) debt, and the red line shows yields on Australia’s foreign debt owed in British pounds.

From December 1929, yields started to rise on bonds trading on both domestic and foreign markets, reflecting a fear of possible default creeping into investors’ minds.

Yields on domestic bonds reached almost 13% in July 1931, just before the default. With general price inflation running at 10% deflation this equated to real bond yields of around 23%, which was similar to Greece’s March 2012 haircut deal on Greek bonds.

Yields on domestic bonds fell immediately when certainty was restored with the haircut deal, just as they did in Greece.

However, yields continued to rise on Australia’s foreign bonds in the London market, due to fears that Australia would have to mandate a restructure of its foreign debt as it had done with its domestic debt. Foreign investors were given a further scare when the Commonwealth government failed to pay interest due on NSW debt in London on 1 Feb 1932. This was a relatively ‘minor’ default, but still technically a default, quickly rectified.

Yields in both markets started to fall steadily during 1932 after the conversion was put in place and after Joe Lyons replaced Jim Scullin as Prime Minister. By July 1932, yields in London were back below 5% for the first time since 1928 and in October the Commonwealth did a successful raising for NSW in London on a yield of 4%. Confidence was restored and the crisis was over.

In part 3 of this story we look at the investment returns achieved by bond investors before, during and after the debt default and restructure. The outcomes are rather surprising.

Ashley Owen is Joint CEO of Philo Capital Advisers and a director and adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund.