The parallels between today’s inflation and the inflationary period of the 1970s are stark.

Australia's inflation-stricken period of today was largely brought about by a rapid increase in the money-supply, in tandem with significant government spending to combat Covid.

In many respects, it mirrors the massive fiscal spending in the mid-70s which occurred at a time when loose monetary policy was stoking inflation.

Similarly, the so-called Great Inflation period during the 1970s in the US was spurred by expansionary monetary policies pursuing full employment, at a time of profligate government spending on the Vietnam war and social policies.

The Great Inflation only began to retreat when Paul Volcker became the Fed chief in 1979, and commenced aggressive monetary policy tightening by raising interest rates and curbing the money supply.

Money supply remains elevated

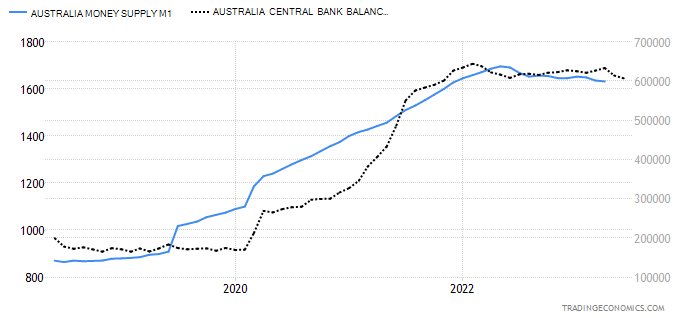

Today the response to inflation in advanced economies has seen rapid interest rate rises, but the money supply thus far has remained elevated by pre-Covid standards, particularly here in Australia, where the M1 money supply measure sat at $1,632 billion at the end of April, up more than 50% on pre-pandemic levels (see chart).

The increased money supply coincided with the RBA’s Quantitative Easing (QE) program which saw it accumulate some $330 billion of Australian government and semi-government bonds, expanding its balance sheet in the process (again, see chart). So would not reversing that QE, known as Quantitative Tightening (QT), have the opposite effect in sucking money out of the system and subduing inflationary pressures?

QE recall, involves the RBA purchasing longer-term government bonds to increase bank reserves and encourage lending, which in turn increases the money supply. QE therefore aims to lower borrowing costs and stimulate investment, a consequence of which could be higher inflation.

Quantitative tightening

The exact reversal of QE is known as active QT. This occurs when the central bank sells its balance sheet assets back into the secondary market before they mature, reducing its balance sheet rapidly, and taking base money out of the system.

Instead the RBA has chosen to implement passive QT, whereby it allows its bond holdings to mature over time and to not reinvest the proceeds. In this way, the central bank balance sheet contracts more slowly.

Specifically, when government bonds held by the central bank mature, deposits held at the central bank by Treasury fall by the same amount to pay for the maturity. Treasury issues new debt to the market to replace its central bank deposits, and banks buy the securities reducing their reserves held as liabilities by the central bank. The central bank balance sheet therefore contracts by the amount of debt maturing, and the reversal of QE is complete.

The RBA said in its May board minutes that it had reviewed its “approach to reducing its holdings of government bonds”. And that “the strategy was to hold these bonds until maturity rather than selling them prior to that”. Members agreed that that approach “remained appropriate for the time being”.

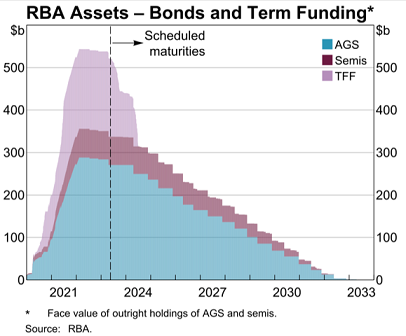

This passive approach recognised that the RBA balance sheet was “already set to decline rapidly given the maturity of funding under the Term Funding Facility” (TFF). But it did not rule out actively offloading its bond holdings in the future, agreeing that “it was appropriate to review the current approach periodically”.

The TFF was basically low-cost funding the RBA offered to banks, fixed for three years, enabling them to on-lend that money at record low interest rates. About $190 billion was drawn down by the time the facility closed in June 2021. It basically complemented the QE program.

Below is a chart showing the projected decline in the RBA balance sheet. Note that it doesn’t return to pre-Covid levels until after 2030. Time will tell whether passive QT will draw money out of the economy fast enough to help stifle inflation.

Other RBA tools to fight inflation

While inflation is proving to be stubborn, draining money out of the system with bond holdings maturing and TFF loans being clawed back, along with the rapid interest rate increases to date, should have the desired effect eventually. And if it needs to kick up a gear, the RBA has even more deflationary levers at its disposal.

It could mandate that banks hold increased reserves, thereby reducing lending, which can restrict spending and investment, dampening inflation.

In a similar vein, it could influence stricter lending standards, preventing excessive lending and reducing inflationary pressures.

Forward guidance. In much the same way the RBA influenced aggressive bank lending by verbally communicating that interest rates were likely to stay near zero until at least 2024, it could put that practice in reverse to influence expectations and put downward pressure on inflation.

It could intervene in currency markets. All else being equal, a stronger currency could weaken export competitiveness, lowering export demand and possibly inflation.

The extent to which the RBA employs these tools, if at all, can vary depending on economic conditions, bearing in mind that it must promote overall economic stability. Meanwhile, the interest rate lever will remain the headline act until such time that the inflation beast has been tamed.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.