The recent annual meeting of global central bankers at Jackson Hole came at a time when investors are beginning to question the wisdom of ongoing extreme monetary stimulus. Contrary to many critics, my concern is not that these measures have not worked. Rather, I maintain they’re simply not needed, as the global economy is as good as might be expected once allowance is made for slowing potential growth and falling commodity prices. To my mind, the far bigger global risk now is the impact of persistent misguided extreme monetary measures on financial stability.

Global growth has been OK

Global economic growth in recent years has been commonly perceived as disappointing, which in turn has been attributed to the scale of the financial shock endured in 2008. Indeed, in developed economies – which are most responsible for today’s extreme monetary measures – annual GDP growth among members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) averaged 1.7% p.a. in the five years to end-2015, compared with 2.8% p.a. in the five years to end-2007.

Around half of this slowdown has reflected a decline in working-age population growth (from 0.8% p.a. to 0.2% p.a.), with the other half reflecting weaker growth in GDP per working-age person (i.e. weak productivity). In other words, most of the slowdown in growth among developed economies since the financial crisis has reflected weaker potential growth.

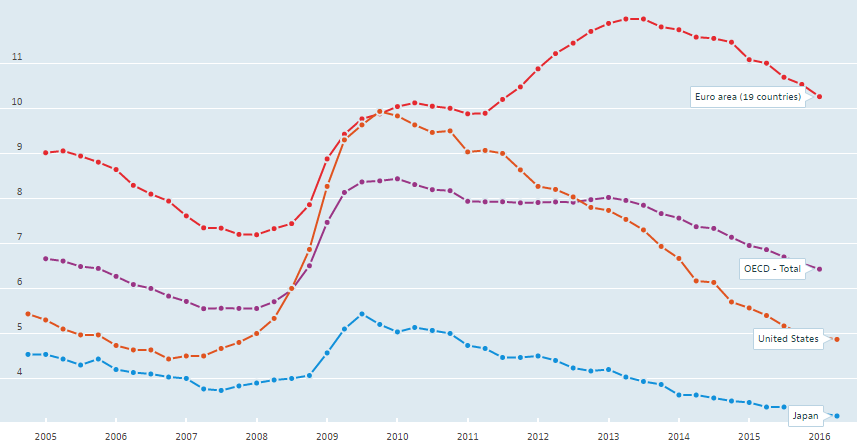

Indeed, as the chart below shows, economic growth across the developed world in recent years appears to have been above potential, as evident from the fact that unemployment rates have trended down. The unemployment rate averaged across the OECD has declined from a peak of 10.4% in March 2010 to 6.4% by March 2016. Only in Europe is the unemployment rate still clearly above GFC lows, but it has also fallen notably in recent years.

Unemployment rates in selected OECD economies

Source: OECD

The Reserve Bank of Australia acknowledged decent growth in the developed world in its August 2016 Statement on Monetary Policy, stating, “Labour market conditions in most advanced economies have continued to improve and a number of these economies are close to full employment.” Crisis, what crisis?

Global inflation is not perilously low

The argument that inflation across the developed world is perilously low, suggesting we are at risk of a deflationary slump, also does not stand up to scrutiny.

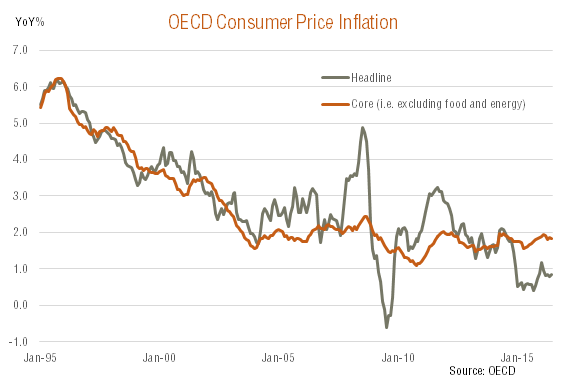

As the chart below shows, headline consumer price inflation across the OECD is relatively low at present, with prices up 0.9% in the 12 months to 30 June 2016, compared with an average since 2004 of 2.1% p.a. Most of this drop in inflation reflects the decline in commodity prices in recent years. In the year to 30 June 2016, core OECD consumer prices (i.e. excluding food and energy prices) were up 1.8% – equal to their (relatively stable) average since 2004.

The case for extra-ordinary monetary stimulus in most of the OECD seems very weak. In the case of the Euro-zone, growth has also been above potential, though the unemployment rate remains elevated compared to pre-financial crisis levels. It’s also the case that core inflation in the Euro-zone is below average. Europe seems to warrant somewhat more monetary stimulus than Japan and the United States, but even in Europe the case for extreme monetary measures seems weak – unemployment is trending down and core inflation is still comfortably above zero (at 0.9% in the year to 30 June 2016).

Financial instability is the biggest risk

Against this backdrop, it is staggering that key policy interest rates are still near-zero in many regions, and central banks have massively enlarged their balance sheets through aggressive buying of financial assets. Japan is the most extreme example, with the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet now almost equal to that of Japanese GDP even though core inflation is above average and the economy is close to full employment!

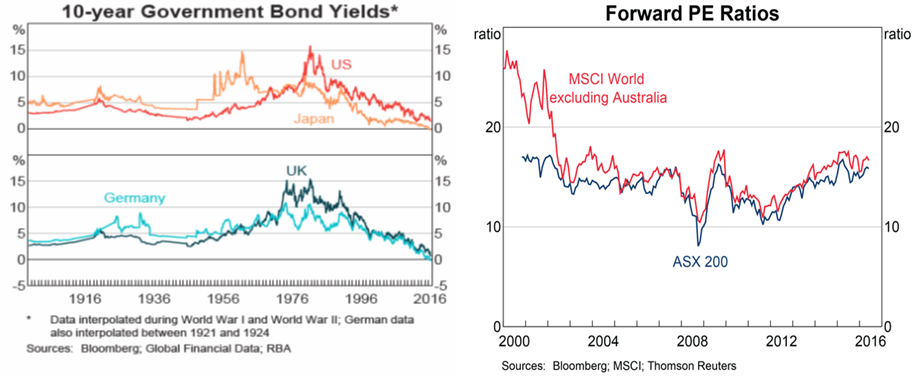

The impact of these extreme monetary measures is highly distortionary for the global economy. As the charts below show, sovereign 10-year government bond yields are now at their lowest levels in at least a century, and price-to-earnings valuations across many markets are approaching levels that have not been sustained since the dotcom bubble period earlier last decade.

The worry is that the bubble in bond yields now appears to be slowly but surely flowing through into equity valuations. Unless global central banks change course – and correctly recognise the reasons for apparently low global growth and inflation have little to do with deficient demand – they are at risk of creating yet another boom-bust cycle in asset prices within the next year or so.

We’re heading the wrong way and it’s time to turn back.

Investment implications

For investors, the implications of aggressive central bank policy actions represent a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, despite weak global earnings, maintenance of easy credit policies may well push up global equity markets over the near term as price-to-earnings valuations (while now above average levels) are still reasonable value against the very low global bond yields on offer. As equity markets continue to rise, the risk increases of a harder and more destabilising decline in equity markets later.

While it is difficult to time when the current market euphoria will end, we are entering a period when increased caution is warranted.

To the extent investors still desire some exposure to the market – if only because of the attractive dividend yields on offer – they might consider more defensive high-income focused sectors and strategies or risk-managed equity products which offer more downside protection.

David Bassanese is Chief Economist at BetaShares. BetaShares is a sponsor of Cuffelinks, and offers risk-managed Exchange-Traded Funds such as listed on the ASX such AUST and WRLD. This article is general information and does not consider the investment circumstances of any individual.