January 2017 may well set the tone for the rest of the year, one of disruption to the economic and political order and a resetting of the way the US does business. The end to US hegemony is here and it is being driven internally as President Trump and his team focus solely on the needs of America and step back from self-imposing itself as both role-model and policeman for the globe.

For the first time since 2007, global macro markets will react differently to economics and politics in a way that may seem counter-intuitive. There is a further risk that past correlations between asset classes will weaken because the baton has been passed from central bankers to politicians, whose reaction functions are difficult to ascertain and change constantly with the political wind. While markets originally feared this switch, they are now embracing it wholeheartedly as the prospect of a move away from the regulatory hell of the last few years to more overt capitalism holds much allure.

A rejection of trade ideals

This article looks at why voters and markets are rewarding a rejection of the liberal ideals that purport open and frictionless trade as the only way forward. They are demanding a move away from the old guard that defends a political structure (e.g. Europe) that does little to benefit the people as a whole. This acts as a wealth creating and protection mechanism for the privileged few who have amassed the most wealth over the last 30 years. The populist voice has been heard and it is positive for economics and markets and therefore we expect this to run much further and much faster.

That said, while we believe the key beneficiary of these changes will be the US, the rest of the developed world should be pulled along in its slipstream. We have concerns though on two fronts: firstly, that the Fed is likely to raise rates aggressively as fiscal stimulus risks overheating a capacity-constrained US economy and this is likely to sow the seeds of the next recession. Secondly, while we believe that US dollar strength will be mild against the majors we fear that the emerging market economies and currencies (Asian especially) will suffer materially.

Market performance this year post the two main wildcards, i.e. Brexit and Trump, suggests that the market instead of fearing the unknown of first time politicians on populist tickets has been quick to embrace the change. The Trump election had the air of the divorcee’s mantra ‘anything but this’ and a change was sought no matter the size of the risk and the potential costs. Sometimes it just becomes an emotional rather than a rational decision.

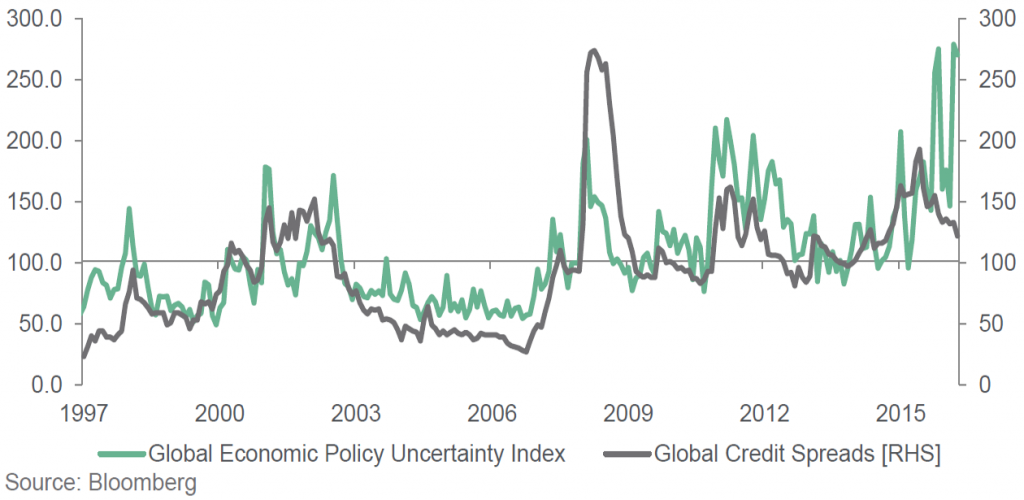

This muted reaction to political swings away from the center and towards too far-right and far-left (which are the same thing these days) was highlighted by the response to the Italian referendum. After a short hiccup it was back to normal programming which was trading for risk-on. A lot of people have been pointing towards the gulf between political uncertainty indices and risk markets (whether they be equities or credit), suggesting that risk markets are incorrectly ignoring political risk. We think there is a chance that both are right and while uncertainty is high, this delivers a change which is ultimately good for risk assets hence their strong performance.

Chart 1: Markets are starting to look at political risk another way

Theresa May’s announcement of the roadmap for Brexit was one of the highlights of January. It represented another point at which markets have clearly changed their view on what is ‘bad’ and what is ‘good’. There are several other examples of this switch in market psychology that have occurred over the last few months. Marie Le Pen may win the next French election but markets have not responded much, apart from a widening in French OAT v German bund spreads. Greece has even fallen off the radar again despite some ridiculous ‘can kicking’.

The old thinking is that less free trade will mean an increased cost of goods as they will not be created as efficiently as before, resulting in lower consumption and therefore less economic activity. This is tough to argue against, as a result it will decrease global aggregate demand growth even below where we are now. This is a disaster, right? Perhaps not, as with most things the quality of aggregate demand may mean more than the quantity of it, especially when wealth and income inequality is as disparate as it is currently.

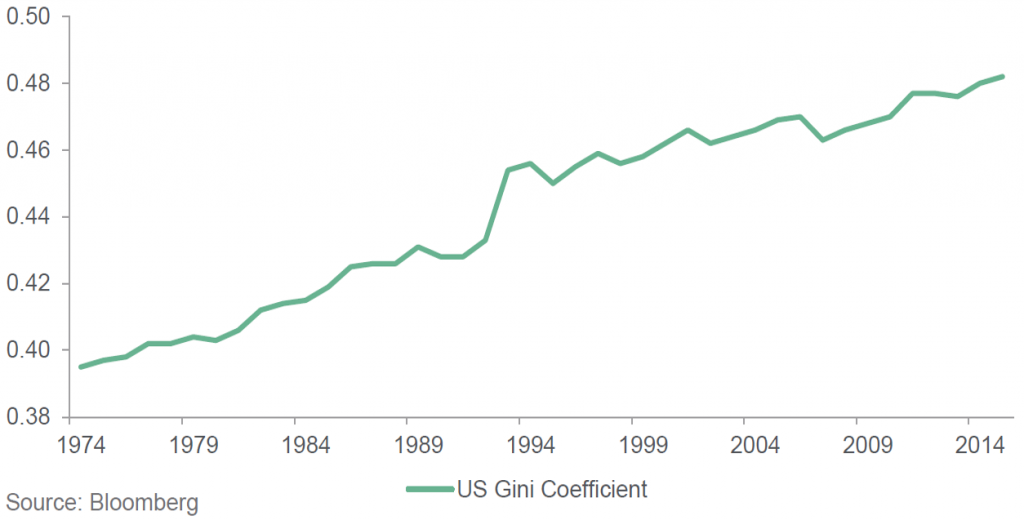

Chart 2: Wealth inequality is the most damaging macro trend

The benefit of free trade and globalisation is actually one of the few things the majority of economists agreed upon as the power of comparative advantage was appealing theoretically and was able to be viewed empirically. It makes sense to smelt aluminium in countries where electricity is cheap, freeing up resources elsewhere to be used more efficiently. It takes the idea of job specialisation in a local economy (we don’t all grow our own food because there are farmers that can do it better and cheaper) on the global level. This almost unanimous appreciation of globalisation has meant that Trump’s protectionist stance has been presented as more proof that Trump’s policies are just populist, taking advantage of an angry middle America who just do not know any better.

When globalisation might not work

But what happens if globalisation only works in the rare case where everyone is an honest and open participant in the game? Consider two countries trading with each other. Similar to most ‘game theory’ problems in finance, the best outcome occurs when there is cooperation between the countries. Both eliminate tariffs, allow freely floating currencies, protect no industries and enforce the same quality of life for their citizens. This way the best industries in each country will thrive there and everyone will have a better quality of life. But if one country has far more advantages than the other (whether it be through resources, education etc.), a trade imbalance will open up and the currencies will adjust to eliminate it. The movement in the currency makes the workers of the poorer country cheaper to the richer, encouraging some industries to move production across which evens everything out again. This is great, if it happens. Trade between Australia and New Zealand can mostly be categorized this way, so it can work.

The problem arises however when ‘cheating’ becomes prevalent it can destroy the whole idea of globalisation being mutually beneficial. Cheating can mean protecting industries in other ways apart from tariffs, such as cheaper financing, subsidies, less rights for labour etc. If one country can successfully do this, it will end up owning a large piece of the other country as the former will need to fund the other’s trade deficit for years to allow them to buy stuff.

In the relationship between the US and China, this is exactly what happened. The trillions of dollars in Chinese reserves (held largely in US Treasuries) accumulated over the first decade of this century is proof that the currency wasn’t being allowed to correct for huge trade imbalances that were opening between the two countries. Economists were saying during this time it was proof of the comparative advantage China had, especially in manufacturing. Labour was definitely cheaper, but was it more to do with the fact that the lack of any labour protection laws gave Chinese labour an unfair advantage or the lack of any environmental regulations in China? While these factors may be considered a comparative advantage (the environment can be considered a resource that can be squandered like oil or iron ore), stepping backwards on labour rights or environmental protection would result in a lower quality of life which may be even worse than losing good paying, manufacturing jobs.

The question you may ask is why would the US subject itself to being cheated like this for such a long time? If China is the winner, surely the US was the loser. People knew they were losing jobs, and they knew they were losing them overseas, mostly to China. But the crucial point was not everyone in the US was a loser and this was key to why the last election went the way it did.

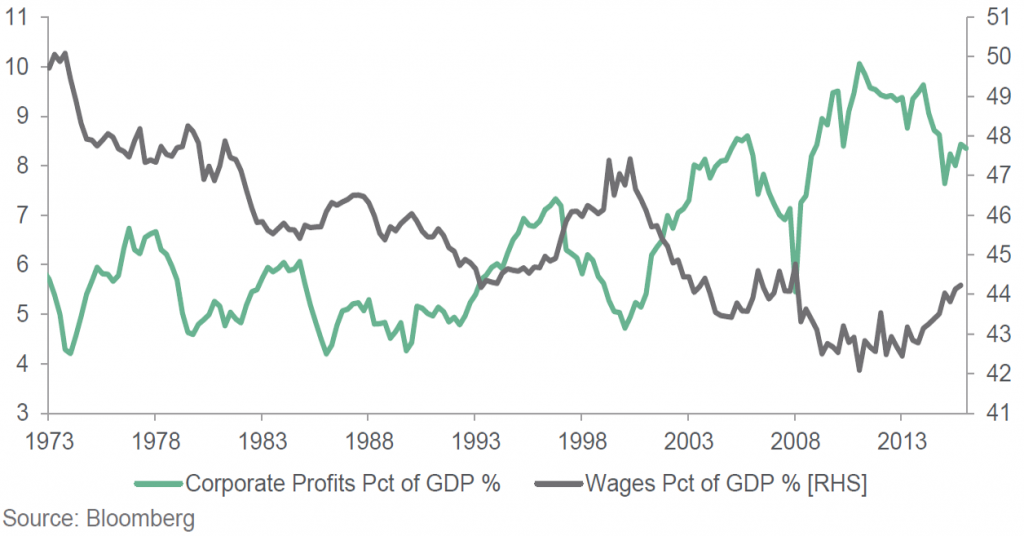

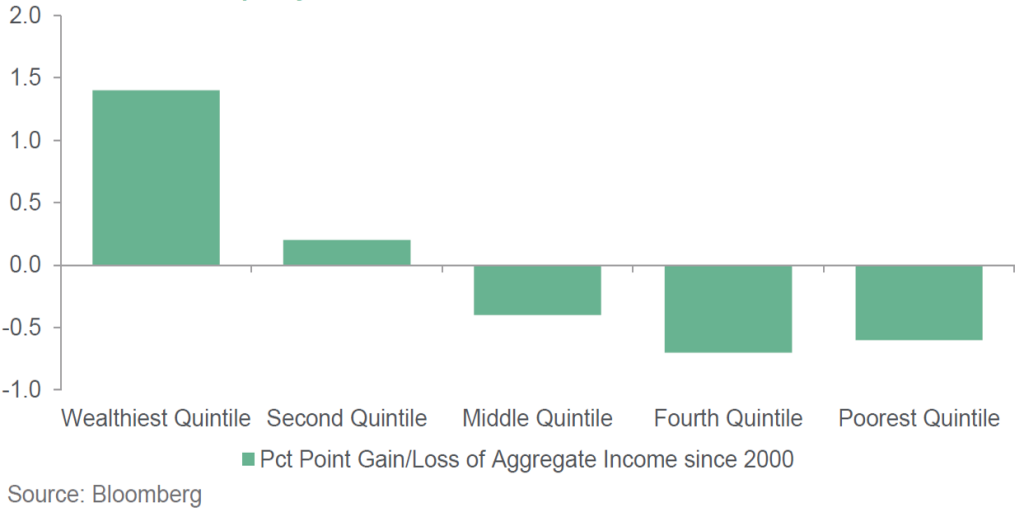

The beneficiaries of China being a cheap producer was the US corporate who could expand their margins while lowering prices by taking advantage of the cheap offshoring that China offered. Corporate profits as a share of GDP skyrocketed, while wages as a share of GDP kept falling. According to the 2011 US Census, roughly the top 15% of all households own 70% of the equities owned by all households. Wealth accumulated for the top two quintiles, as shown in Chart 4, with everyone below that getting poorer, even though the GFC punished financial assets the hardest.

The fall in the value of housing through the GFC hit the poorest disproportionately of course, but the credit that caused the housing boom in the first place is also rooted in issues with trade. Additionally, these more powerful corporates started to ‘own’ the government through lobbying, ensuring their continued success.

Chart 3: …and the effects can be seen everywhere

Chart 4: Income disparity has worsened since China entered the WTO

The theory of globalisation has made a lot of people rich beyond what could ever be imagined in the post-war period. The fact that eight men are now wealthier than half of the world’s population highlights the absurdity of this phenomenon.

Unwelcome consequences of a trade war

There are other policies that anger the Trump haters. One particular topic is the environment, which Trump appears not to care about one bit, enraging those who put it at the top of their global issues. We mentioned before that labour rights and the environment were two very big factors giving China the advantage. The EPA has been extremely aggressive in forcing through environmental regulations in recent history, increasing the cost of compliance for industry and widening this gap. While this is admirable, it makes the job of re-shoring all that much harder, and Trump knows it. Slowing down the increase in cost of compliance will put the US in with a fighting chance. He also knows that moving further away from fossil fuels will reduce competitiveness against countries that have no qualm in abusing them. In the end a trade war could be one of the best outcomes for the environment.

However, whilst a trade war may drive up growth and inflation in the US while reducing wealth inequality, the effect globally will be nowhere near as positive. This will slow Chinese and EM growth, reduce commodity consumption and be deflationary for the rest of the world. If it works you can count on more countries doing it, worsening the effect.

The investment story is a very US-centric one now which is concentrating on the positives there, but ignoring the serious effects elsewhere. The global story will surely eventually drive bond yields lower once again, albeit from higher levels, and this is even before considering the difficulties and tail-risk in Europe. Right now, the global market is still feeding from the Chinese credit growth, plus the belief that Trump policies will drive not just US growth higher, but global growth. While Trump may end up delivering a better outcome for middle America, the rest of the world will suffer. Trade has already been slowing before the protectionist policies have even begun and it is not difficult to foresee the reversal of 20 years of global 'free' trade.

Vimal Gor is Head of Income & Fixed Interest at BT Investment Management. This is an edited version, the full copy is linked here. The article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.