Shifting monetary policy across developed markets has forced many investors to consider the risks involved in holding U.S. and Australian Treasuries. After six years of unprecedented liquidity, the U.S. Federal Reserve is tapering its asset purchases, and could start raising interest rates in 18-24 months. In Britain, unemployment is declining faster than expected, prompting debate that the Bank of England may raise interest rates next year. Over the longer term, interest rates will rise, and investors should understand the inherent risks in so-called ‘risk-free’ assets, given their limited return potential.

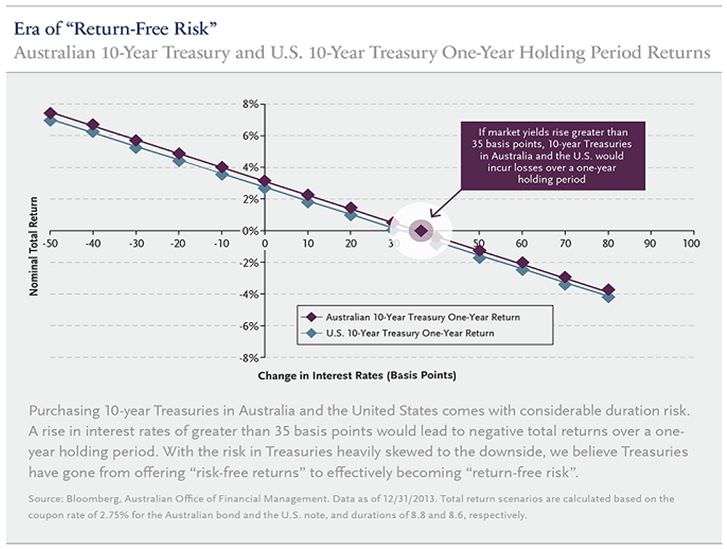

Although interest rates have risen over the past year as the U.S. Federal Reserve began talking about withdrawing monetary accommodation, even at current yields we question whether U.S. Treasuries sufficiently compensate investors for interest rate risk. The interest income earned from recently issued 10-year U.S. Treasury notes would be negated by the loss incurred from a 0.30% increase in interest rates over a one-year holding period. The same risk is present in the 10-year Australian government bond, where a 0.35% increase in interest rates would have the same effect on the Australian Treasury bond maturing 21 April 2024. But yields remain artificially depressed from several years of expansionary monetary policy. U.S. 10-year government bonds yield 2.7% and Australian 10-year government bonds yield 4.2%, below their historical averages of 6.5% and 7.9% respectively. We believe Treasuries have gone from offering ‘risk-free returns’ to effectively becoming ‘return-free risk’.

Broad benchmarks, which often dictate the way investments are allocated, reflect the composition of a market. The Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (‘the Barclays Agg’), the most widely used proxy for the U.S. bond market, is now over 70% concentrated in low-yielding U.S. government-related debt. Soaring fiscal deficits have increased outstanding U.S. Treasury debt by 255% between 2007 and 2013. The Barclays Agg yields only 2.3% and few compelling yield alternatives remain within the ‘core’ fixed-interest landscape, making it more difficult for investors to meet total return targets. The same is true beyond the United States and we think investors globally should move away from the traditional view of core fixed-interest management into a broader investment framework.

Value in a broadened investment framework

Over the past few years, aversion to non-traditional, riskier assets such as high-yield debt, structured credit, and emerging-market debt, has waned as investors seeking yield took on more credit risk. This approach can be successful if the investor has the resources to conduct in-depth credit analysis. A larger, more diversified portfolio can benefit from actively assessing relative value and shifting portfolios toward the best value proposition, called a ‘multi-credit strategy’.

In a multi-credit strategy, managers actively assess three major components during the portfolio construction process, while remaining driven by long-term views:

- Sector valuation. Is the sector overvalued or undervalued? How do valuations compare to historical levels?

- Risk assessment. What are the major macroeconomic and sector-specific risks? Does each sector fairly compensate for the risk they carry?

- Relative value. Can another sector offer better returns for the same duration or credit risk? Is our outlook more positive for one sector relative to another?

Just as important is the risk management component, which considers diversification and correlation, among other factors. By properly assessing these components and shifting portfolio allocations toward the best value proposition, investors can steadily outperform a broader benchmark over time.

A multi-credit strategy should be tailored to individual needs. Some investors have the tolerance to tilt toward less liquid, more research-intensive sectors which typically offer premiums for their lack of liquidity and relative complexity. This is where Guggenheim believes there is most value. For other investors with higher liquidity needs, a multi-credit strategy can focus on high quality, liquid sectors. For example, last year’s U.S. Treasury sell-off spread into investment-grade U.S. municipal bonds, where credit spreads widened to levels not seen in over two years, moving beyond what we felt was fair given our constructive view on specific credits. The sell-off created a temporary buying opportunity in municipal bonds which offered higher yields than in 2012, for the same credit risk. These short-term buying opportunities can ultimately be a source of long-term outperformance for investors with the flexibility to take advantage of them, while remaining long-term oriented on the overall strategy.

The Barclays Agg is overweight in government-related debt, resulting in its lacklustre yield and making the traditional approach to fixed income investing antiquated. In today’s low-interest rate environment, we believe investors need to take a different approach to generate better returns. Over the past year, such better returns were achieved by increasing allocations to corporate bonds, residential mortgage-backed securities, commercial mortgage-backed securities, municipal bonds and asset-backed securities. This approach can increase a portfolio’s yield by more than 200 basis points over the benchmark.

Intuitively, a multi-credit approach would increase tracking error, a measure of how much a portfolio’s performance differs from its benchmark. We think increasing tracking error for the potential of achieving higher returns is justified. Remaining tightly aligned to broad benchmarks leaves investors without the flexibility to take advantage of undervalued sectors.

Scott Minerd is the Global Chief Investment Officer and a Managing Partner of Guggenheim Partners, LLC, a privately held global financial services firm with more than USD190 billion in assets under management. Principle Advisory Services is Guggenheim Partners’ distribution partner in Australia and New Zealand.