This is the first of a two-part series exploring the focus on liquid assets in defined contribution schemes.

Superannuation is a long-term investment strategy. This is being reinforced by proposed increases in the retirement age and trend towards new investment models (like life cycle investing) looking ‘through’ retirement age for investment strategy. The focus on long term investing should therefore be of paramount importance for superannuation investors.

However, in contrast to the approaches of other long-term investing institutions, the defined contribution (DC) market seems to be obsessed with very ‘liquid’ investments. Liquid here means the ability to convert investments to cash in a speedy manner (or to be ‘cashable’). This trend is particularly evident in Australia as its DC system is one of the largest and well established in the world.

Spot the difference

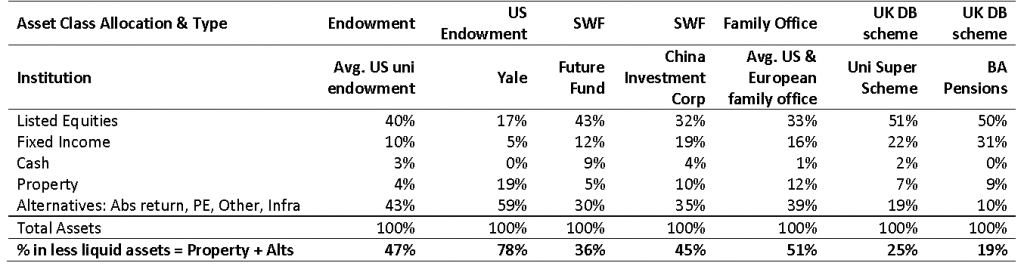

Comparable long-term investing institutions with superannuation funds include Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs), family offices, defined benefit (DB) pension funds, foundations and university endowments. Each has a long-term horizon to meet their investment objectives. Each views its strategic asset mix as a significant decision which establishes the investing framework. And each of these uses a blend of external and internal advisors to assist in setting their long-term asset mix. Essentially, they pay to receive the best advice globally on how to manage money over the long term. So how do they manage their money?

Table 1 illustrates how these long-term investors set out their strategic asset investing framework. Less liquid assets include alternative assets such as direct property, private equity, infrastructure, hedge funds, real assets, timber, physical natural resources and other physical assets:

Table 1: Long-term investors, typical strategic asset allocation

Source: Latest annual reports and accounts of each institution; Wharton study of global family offices.

The percentage of less cashable assets for these types of long-term investors ranges from a low of 19% to a maximum of 78%.

The table also identifies one of the icons of alternative investing, Yale Endowment, which boasts the highest allocation to less cashable assets at 78%. Despite living through the global financial crisis, Yale still maintains this allocation, including a substantial 32% to private equity and 18% to absolute return strategies. Its long-term performance is 13.5% per annum over the past 20 years, a track record that is the envy of many other institutions. And despite holding only 22% of its assets in liquid cashable form, the endowment still contributes 34% of the Yale University operating budget. Some commentators would claim that this focus on long-term, less liquid strategies is the hallmark of a true long-term investor.

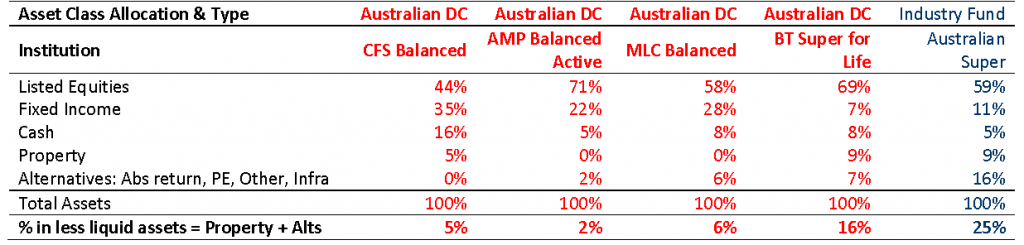

Looking at Australian DC schemes, Table 2 shows the same asset allocation breakdown:

Table 2: Australian defined contribution schemes, typical asset allocation

Source: Latest report and accounts of four public offer (retail) Australian DC Funds plus one large Industry Fund.

Source: Latest report and accounts of four public offer (retail) Australian DC Funds plus one large Industry Fund.

The first four red columns are public offer, retail super funds. The table shows how domestic DC schemes have a far greater focus on liquidity, with only 2%-16% in illiquid assets. Whilst average and up-to-date data is hard obtain, many SMSFs also look similar to these four funds. These two segments comprise nearly 60% of the assets in superannuation, making the impact of their decisions significant. And quite surprising given the long-term objective.

The final blue column in Table 2 is Australian Super, one of the large industry funds. Industry funds collectively represent approximately one fifth of superannuation balances. This fund’s asset allocation looks closer to the other long-term institutions. However the asset mix in less cashable investments remains heavily concentrated in just two areas: infrastructure and direct Australian property deals, rather than spread amongst a wide variety of asset types. This implies a less diverse approach to less liquid assets.

Why is DC in Australia so different?

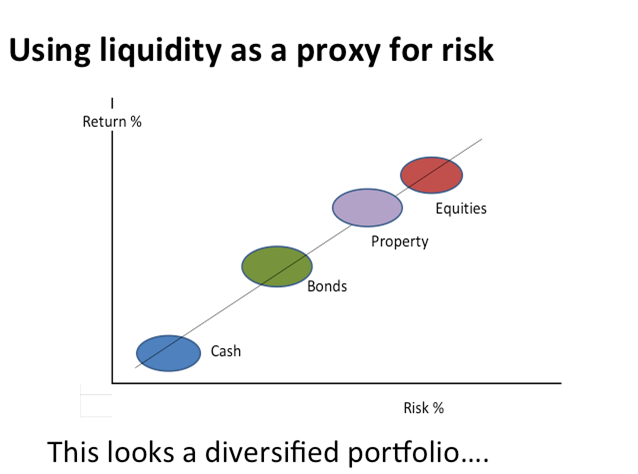

If other global institutions armed with the best advice on how to meet their long-term objectives hold a high proportion of less liquid assets, why is DC in Australia so different?One theory is that the Australian investors confuse liquidity with safety. That is, they like to stay cashable because they are using liquidity as a proxy for risk.

Diagram 1 outlines a typical asset allocation using the scales of ‘risk and return’. The asset classes are well spread and appear well-diversified.

Diagram 1: Risk and return by asset class for DC funds

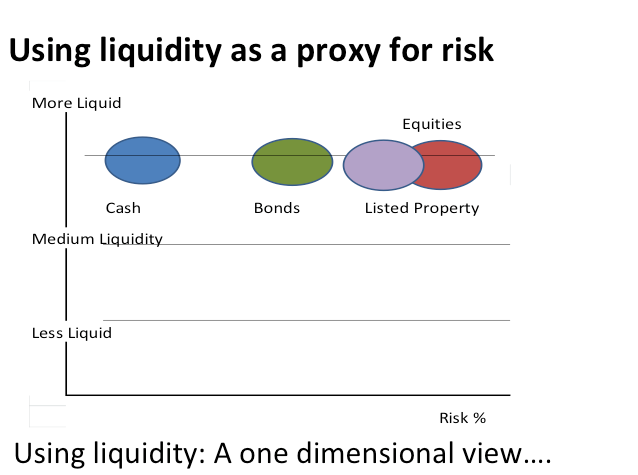

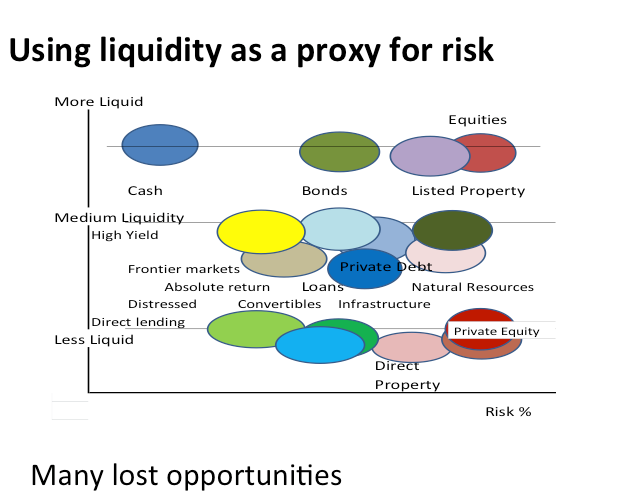

Diagram 2 outlines the same investments but with the vertical axis set as liquidity rather than return. The top horizontal line shows more liquid investments. Below are medium and less liquid investments (assets which cannot be easily sold). It highlights that the DC assets all fall into the more liquid category and so the portfolio is one-dimensional.

Diagram 2: Risk and liquidity by asset class for DC funds

Lost opportunities

The lack of diversification in DC portfolios creates a real disadvantage over other long-term investors because one-dimensional portfolios overlook many other interesting and opportunistic investment types.

Diagram 3: Risk and liquidity by asset class for other global investors

Diagram 3 highlights some of the less liquid opportunities that most DC investors miss. These include absolute return, emerging market credit, frontier markets, structured products, natural resources and infrastructure. These assets don’t all need to always be in a DC portfolio – far from it. In fact, with less cashable assets an opportunistic approach is preferable to pouring in monies simply because there is an allocation bucket to fill. One secret with less liquid assets is to generally invest in areas where others are not herding and look for the ‘less crowded’ trades.

Allocating a proportion of a portfolio into medium and less liquid investments provides three distinct advantages: a different return stream, a mixture of novel market returns which cannot be accessed passively; and a blend of different manager skills (including leverage, shorting, structuring using options and unique pricing models). Not having access to these less liquid investments disadvantages DC investors as they don’t have the opportunity to play to their strengths as long-term, patient and opportunistic investors.

Confusing liquidity with safety

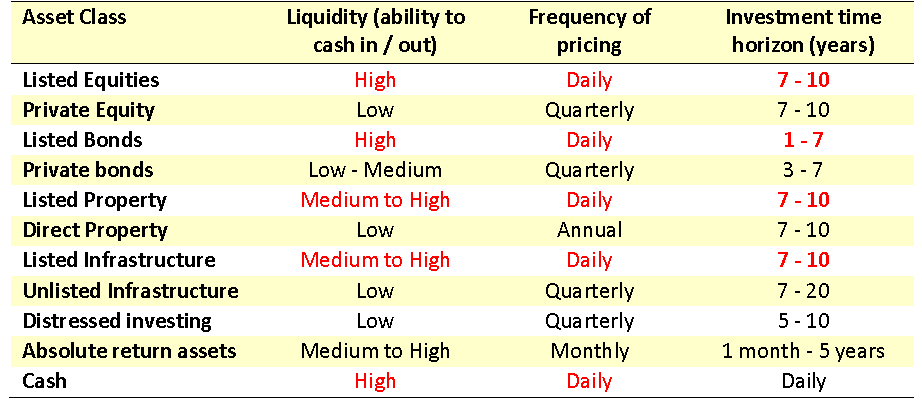

If investors confuse liquidity with risk, it creates perverse outcomes. Consider the liquidity, pricing frequency and horizon of different asset classes.

Table 3: The characteristics of liquid and less liquid investments

Across different types of investments, Table 3 assesses various characteristics: liquidity (high, medium or low), the typical frequency of pricing, and the recommended investment time horizon with red text identifying where frequency of pricing is daily. What is apparent is that in most cases the private market assets have a similar time horizon for investment purposes as the listed version. For example in private equity the recommended time horizon is seven to ten years for both private and public market assets. So an investor using skilled external funds should in theory be ambivalent about investing into either private equity (where the investments are not cashable) or in public equity (where they are cashable).

Focus on the investment time horizon

Believing that an equity security is safe simply because you can exit it on a daily basis belies the investment time horizon that should be incorporated for that type of investment (assuming the investor uses external funds rather than investing themselves). If we assume that DC superannuation investors are not traders nor specialists at market timing then the ability to get into and out of equities on a daily basis is an unnecessary characteristic, given the high-risk level of equity investment.

This highlights a major disconnect: equities are the riskiest asset class and yet because they are priced daily investors feel comfortable investing in them. The same applies broadly to property (direct and listed) as well as infrastructure investing – investors mistakenly confuse liquidity with safety. If a fund manager were to impose a minimum seven-year lock up on an equity fund, it is unlikely that they would attract many investors. Yet most investors should be looking at equities with a long-term, seven year or more investment horizon, not as a daily trading opportunity. Perverse indeed.

The Australian DC super fund obsession with liquidity can be detrimental to retirement outcomes as investors may miss out on many interesting medium and less liquid investments. In part 2, I examine other reasons for this obsession, and question whether DC member choice (as defined in Australian legislation) may be incompatible with long-term investing and leads to sub-optimal investor outcomes.

Bev Durston has over 25 years’ experience in implementing investment solutions for pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and fund managers. She now runs her own advisory business for institutional clients, Edgehaven Pty Ltd.