When directors buy or sell shares in their company, most people believe they are sending a strong signal to the market about the firm’s prospects. But how strong is the correlation between director trades and share price movements? And should you buy or sell because a director has too? We did some research to get closer to the truth.

It seems reasonable to think that company directors have better insight than the rest of us into the performance and prospects of a business, and that they may be more willing to buy when they see a rosy outlook, and sell when the outlook is dim.

Of course, regulation and governance should greatly limit the extent to which company insiders take advantage of their privileged position, but one suspects that these constraints may mitigate against the application of insider insight, rather than completely eliminate it.

This discussion has become more topical recently, with some high-profile examples of director selling that now look to be fairly prescient. These include cases like Aconex, Sirtex, Bellamys, Vocus, Brambles and Healthscope, where directors managed to sell shares ahead of falling prices.

Don’t make too much of recent experience

There’s no doubt that director sales have been telling in these recent examples, but there is a strong tendency for investors to extrapolate from limited recent experience, and it’s always good to be a little wary of this. A better approach is to look at what the data says over a reasonable time period to try to gauge objectively how much comfort we can draw from insider purchases, and how much concern we should feel when they sell.

The academic research evidence has been a bit mixed. Some studies have shown that trades by company insiders contain information, but others find little effect, and good research evidence for the Australian market is lacking.

We did some research on ASX director trades. Our work is not of the quality that you might expect from published academic research, but it offers deeper insight than anecdotes.

Our analytical process

- We downloaded the pdfs of ASX300 company announcements made over the past eight years where the title of the announcement indicated a “change in director’s interest” or “Appendix 3Y” (but excluded initial and final director’s interest notices).

- We scanned the text of these announcements and used some rules to identify cases where the ‘Nature of change’ section indicated an on-market trade, and excluded cases where the change appeared to result from an issue of shares under company incentive plans and the like.

- We used some further rules to extract numbers from the ‘Interest Acquired’, ‘Interest Disposed’ and ‘Value/Consideration’ sections of the announcements. We will have missed some trades for various reasons but we had a good representative sample of either years of data.

- We then looked back six months (ie. considered director trades made in the six months prior to our observation date) and examined risk adjusted returns over the subsequent three months.

Our research findings

- Director selling appears to contain more information than director buying. This is consistent with some academic research which indicates selling is a more powerful signal than buying.

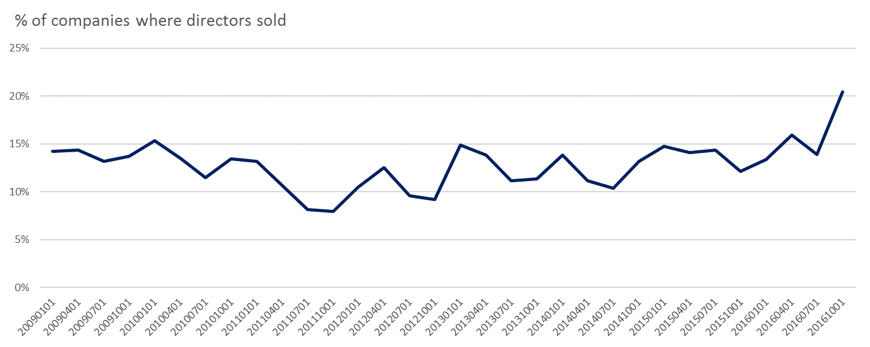

- On average, we found that around 20% of companies had one or more director share sales occurring in any given six month look-back period. Interestingly, the most recent data shows a relatively high proportion of director selling, which could indicate a general perception by directors that prices currently are at elevated levels.

- Seasonality to director selling is apparent, with the peaks in January indicating that the second half of the calendar year – and the final quarter in particular – is the most popular time to sell.

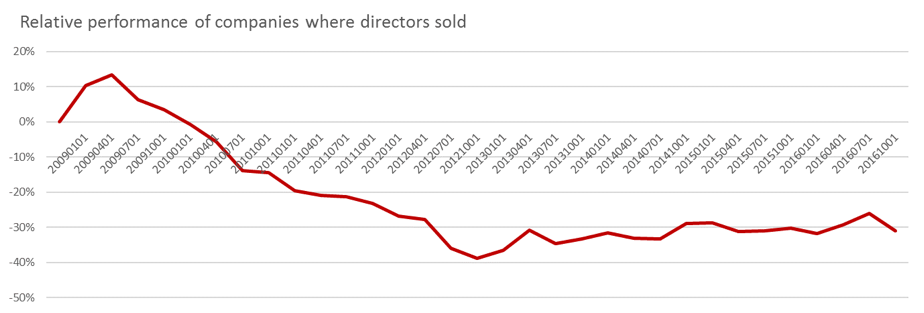

- Because the director sales occur in a relatively small proportion of our universe (about 20%), we need to keep the returns analysis simple. We divide our companies into two groups: those where no director sales have been identified in the past six months, and those where at least one director sale has been found. We form equal-weighted portfolios from these two groups and rebalance every three months.

- As a general rule, the companies where directors had sold shares tended to perform worse than companies where no director sales had occurred. On average the difference between the two groups seems to run to a couple of percentage points per year, but the pattern is far from consistent. Most of the performance differential occurred between mid-2009 and late-2012. In recent years, we have seen only a small differential (although the final quarter of 2016 was a good time to avoid companies with director sales).

It’s worth watching director sales

We conclude that when company directors sell shares, it is not necessarily an overwhelming signal that others should follow suit. However, it clearly should be considered as part of the analysis. As is often the case, common sense should prevail, as a sale should prompt you to:

- Consider the specific circumstances and whether it may be motivated by a negative view on firm prospects or something more benign.

- Think about whether the relevant director has a large information advantage and is much better placed than you to gauge long term value.

- Reflect on your valuation assumptions and importantly, your level of conviction in them.

Tim Kelley is Head of Research and Portfolio Manager of The Montgomery Fund. This article is general information that does not consider the circumstances of any individual.