[SPOILER ALERT: In the previous article in Cuffelinks, we reproduced the 13-part questionnaire from the start of the Factfulness book, designed to test your understanding of world affairs. You will benefit most if you attempt it before reading this review. Consider buying the book, it’s only $20 including postage.]

When Hans Rosling and his family founded the Gapminder Foundation in 2005, their mission was “to fight devastating ignorance with a fact-based review”. ‘Devastating’ is a strong word, but he has done us all a good service. As the book takes the reader systematically through dozens of worldviews where the majority of people hold wrong opinions, the most obvious question is ‘why?’ Why do the best-educated people know so little about global trends in population, health, education or demographics despite watching and reading the news every day? In fact, says Rosling, “the most appalling results came from a group of Nobel laureates and medical researchers.”

Rosling concludes we have an overdramatic worldview because of the way our brains work. After millions of years of evolution, the brain is designed to jump to immediate conclusions without much thinking, which once helped us to avoid attacks by sabre-toothed tigers. We are most interested in gossip and drama in the same way we crave sugar and fat, which were once a vital sources of energy. Obesity is a growing problem despite education about healthy food, in the same way our news instincts influence our worldview.

Our daily media consumption feeds this obsession with drama rather than reporting the gradual incremental progress the world is really experiencing. News delivers sensational stories rather than a wider perspective, and much of it is disproportionately emotional and negative and encourages quick conclusions.

Close parallels with Daniel Kahneman

There are similarities with the arguments of Nobel Prize-winning behavioural economist, Daniel Kahneman, and his System 1 and System 2 thinking. He says there are two ways we make decisions: System 1 is automatic, fast, often subconscious and intuitive, while System 2 is slower, logical and deliberative. But System 2 also takes more effort, so we fall back on System 1 even for important decisions. It has implications for many activities, including investing, where we react in irrational ways to minor events. Similarly with Rosling, the drama of the immediate news cycle forces us into opinions and thoughts and often we do not take a slower, more logical look at the issues.

What happens when you dive into the facts?

Rosling has no less an aim than to change the way people think and calm irrational fears. When people strip away the drama of the headline, they can be more hopeful about the world. He encourages critical analysis rather than instinctive thinking. It’s like a healthy diet with more exercise and better food. You can even stay more alert to real danger than worrying about the wrong things. He wants people to return to a childlike sense of wonder about the world.

He also argues that when people think the world is becoming worse, it’s not really thinking, it’s feeling. Consider the selective reporting of the news cycle. Natural disasters, crime, wars, politics, corruption and terror. Most people are less interested in stories about gradual improvements in the lives of millions.

The solution is not to sugarcoat the news, but to keep two thoughts in mind at the same time while maintaining a wider context. For example, the dramatic news item might be that 12% of one-year-olds are not vaccinated, but that means nine out of ten children are. The non-vaccination figure has fallen from 66% as recently as 1980 despite there being two billion more people in the world.

Rosling’s most dramatic example

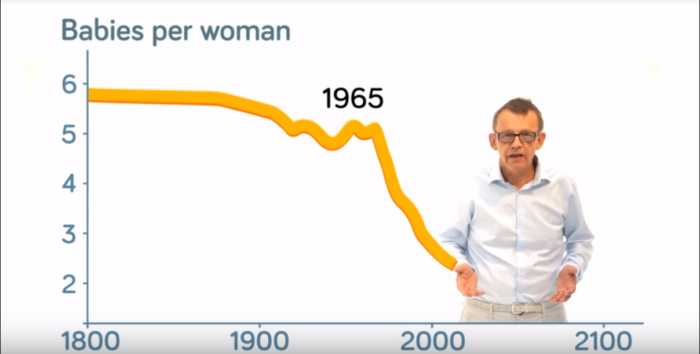

In a book offering many examples to support Rosling’s claims, he says his most dramatic chart is the number of babies per woman from 1800 to today, as shown below in this extract from one of Rosling’s videos.

For most of history, and as recently as 1948, women on average gave birth to about six children each, and now it is headed for only two. This is a vital statistic as it shows billions of people are coming out of extreme poverty. They no longer need large families to toil on a small farm and as insurance against old age and child mortality. Better-educated women have fewer children, aided by access to contraceptives. This also means the period of fast population growth across the globe will soon be over.

My favourite financial example is Rosling’s explanation of why many houses are half-built in Tunisia. It looks as if many Tunisians are lazy or cannot finish a project. Rather, as many Tunisians escape poverty, they have capacity to save but they don’t have access to banks. Money can be stolen or lose its value through inflation. So they buy bricks, but as there’s no space inside to store them and outside they might get stolen, they add their bricks to their house as they buy them. Over 10 to 15 years, they gradually build a better home.

Income defines what everyone in the world buys

In fact, the vast majority of people in the world do not live in extreme poverty or extreme wealth, but somewhere in the middle. It’s not as bad as most people believe and the lives of the majority of the world’s population are somewhere in the middle. Rosling’s powerful example is the distinction between developing and developed countries. Due to the vast differences in lifestyle found within any country, he argues, to label it either ‘developed’ or ‘developing’ can be misleading. He dispels the notion that the standard of living in each country is defined by culture. Rather, he argues, everywhere it is defined by income. Regardless of where a person lives, people of a comparable income tend to buy the same things: not only expensive items like cars and electrical equipment, but even toys and kitchen utensils.

Back strong opinions with strong facts

I admire Factfulness for making the case for less cynicism and ignorance while remaining sceptical about the world. It is not a flowery book making out the world is a wonderful place, as of course there is serious inequity and injustice. But not as much as most of us think and opinions should be more nuanced than extreme.

After reading this book, I challenge myself not to react to the headlines or dramatic news items without considering other facts. Rosling has a simple rule that would surely make the world a better place of informed opinion: only carry strong opinions when you have the supporting facts. Many politicians and media commentators (especially our shock jocks who are frequently held libellous for badly-researched opinions) need to offer a more balanced view and we might not be so pessimistic about the planet we are all sharing.

Footnote: Hans Rosling wrote the book with his son, Ola Rosling, and Ola’s wife, Anna Rosling Ronnlund. They conceived the idea in September 2015 and Hans was diagnosed with incurable pancreatic cancer in February 2016. He died in February 2017, and the book was finished to honor his memory.

The final words in the book are:

“When we have a fact-based worldview, we can see that the world is not as bad as it seems – and we can see what we have to do to keep making it better.”

The writers have also created Dollar Street, an online database on life in different countries.

How did you score in the test? Did you think the world was a worse place than is really is?

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Cuffelinks.