In the six months of my ongoing battle with brain cancer, one part of financial markets has fascinated me whenever I find time to read. It’s probably not what you think. Sure, the Reserve Bank’s ongoing debate about inflation and interest rates has filled economists with anticipation, and global wars have horrified us, making the conflicts almost unwatchable. But one subject that has led the pages of my reading is real estate, especially residential.

The question that hits me every day is: where is all the residential money coming from? Whether it’s $4 million in the inner west, $20 million for a penthouse on the north shore or a $50 million mansion in the east, it’s a continuous surprise to see how much money people have access to.

Real estate is not even my specialty, but the last six months have been both bemusing and fascinating. It’s often difficult to believe that the numbers are true. For example, according to Domain, the average house price in the 2024 March quarter for Sydney is $1.628 million dollars, up from $1.465 million a year ago and up 11.1% in that time. Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane are up even more. Rents have risen almost 8% across Australia, the biggest increases in 15 years. In one year, Sydney’s median house price has risen over $160,000.

It would not have seemed possible a couple of years ago in the face of interest rate increases, of which there were eight in 2022 alone. During COVID, with lending rates falling as low as 2%, a rise of 1% to 2% seemed likely. Homebuyers were doing their numbers as high as 4%, locking in rates for a couple of years where possible. But inflation drove 13 rate increases since April 2022 and have taken cash rates to 4.35%, where rates have stayed since November 2023. Plenty of lenders are now charging 6% or more and cash rates are not forecast to reach below 4% until the end of 2025.

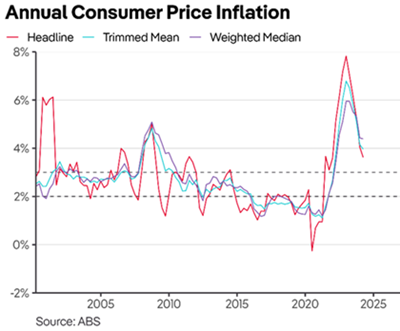

The latest data for 2024 shows the dramatic increase in inflation for the period 2022 and 2023, and the stubborn refusal to fall as much as anticipated this year. Many economists expect only one or two reductions by the end of the year, but some are at zero. The return of inflation to the central bank target range is a long way off.

As a sign how much the market has reassessed its interest rate expectations, the ASX 30 day Interbank Cash Rate forecasts little movement by even the middle of 2025, perhaps a full year with no changes. Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock expects not to tighten again, but nor does she see easing conditions yet. Let’s hope the new structure of the Reserve Bank board does not push her to act before she needs to.

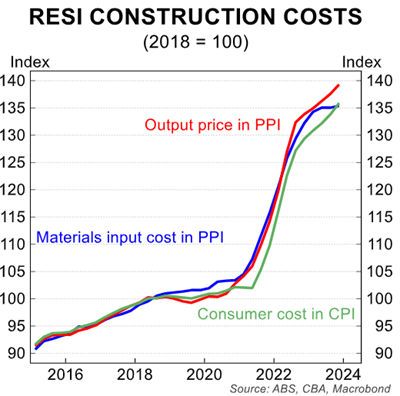

New building is at decade lows, with many trades attracted to the certainty of long-term government contracts rather than the unpredictability of housing. The Albanese Government’s promise of 240,000 dwellings a year looks impossible, even with banks keen to lend. The shortage of materials and inflation on supplies does not help.

Yet there is no shortage of home demand despite supply problems, and home prices, especially for houses, have continued to rise rapidly. This is where new solutions are surfacing.

Borrowers access increasing amounts

First, borrowers are willing to increase their loans with the bank, almost to whatever limit is allowed to secure a home. Whereas 20 or 30 years ago, borrowers relied on accessing three to four times as much of their income, the house price now represents as much as seven to eight times earnings (and it used to be more when rates were lower). Many borrowers will be paying off their principal for decades. The biggest shock for new home buyers has come in construction costs, requiring renegotiation of terms to prevent builders going broke.

There’s more to come. Oxford Economics estimates that between 2025 and 2027, median home prices will hit $1.3 million with Sydney at $1.9 million. Home units will exceed $1 million on average. Thousands of people will need to make the ‘rent versus buy’ trade-off, with a move to new apartments likely given many old houses are in bad condition.

A similar trade-off decision will come from the payoff of student loans, as a debt of $100,000 will go a long way to paying off a home loan. Australia covers three million former students with loans of almost $80 billion. It’s a massive burden to carry (and I come from an era of free university education, which was a major bonus).

Major population growth depends on home and infrastructure building (toilets, roads, sewerage, etc). The Housing Industry Association advised recently that the cost of labour, concrete and materials will delay any increase in the amount of high-rise development for at least another year.

So, borrowers will increasingly look beyond their own financial resources, and with rents at new record highs, people will want to buy rather than face the terrible hassles, short leases and scarcity of renting.

Bank of Mum and Dad

Second, the increase in the role of the Bank of Mum and Dad has changed the market. In prior years, as recently as five to 10 years ago, parents might provide some money to help with extra needs, and maybe as much as a deposit. Now, it is not uncommon to hear a group of people bidding to buy a house and each couple has their parents with them with significant support.

It is becoming so common that parents are now more sophisticated in the ways they lend or give money to their children. Increasingly, terms are negotiated to ensure money is retained if a family breaks up. Parents don’t want to give their children $250,000 only to see it disappear in a marriage split.

Such documentation may upset one of the children. Terms and conditions are written down with clear definitions of obligations each way. A gift to the son or daughter might be split in the event of a divorce. Except for the wealthiest of families, parents should check their eligibility for pensions and income streams is not affected, and their will should be checked and amended. These agreements often require documentation to cover issues such as capital gains tax, and not simply an assumption that the marriage will last forever.

Multigenerational families

Third, it is becoming more common for mutigenerational families to buy and live together. A large house worth say $5 million might not normally be considered by one family. But where they are looking to care for grandparents, cover the long hours that a parent works while also allowing for the needs of the children, homes with three generations living together are becoming more popular.

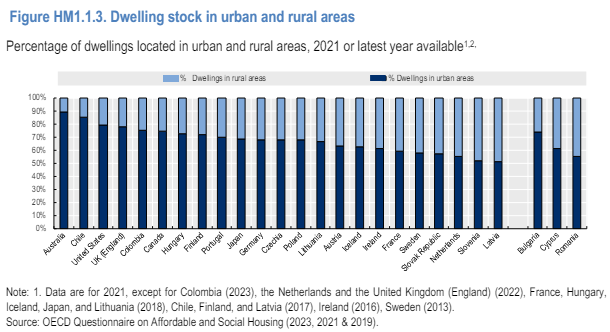

Of course, they might be living close to family rather than in the same house. Australia is unique with a high proportion of dwellings for people who live in urban areas rather than rural and is at the top of the world at over 90% urban, often due to people wanting to live near or with parents.

More people working longer

Fourth is the other side of the generosity of the grandparents. They may delay retirement beyond 60 or 65 by one of them working longer, perhaps while the other looks after the grandchildren. They may now owe more on their house as they borrow for their children, with a third still servicing loans where once they thought it might be time to relax.

Warren Buffett at the age of 93, and before him, Charlie Munger at the age of 99, show that it is possible mixing work and play well into retirement. Many people work beyond 70 (with brain cancer’s permission) with a few days mixing it up. It should be part of the funding discussion with a spouse on financial intentions, even if there is 20 years left to live.

Lots of choices

The days are long gone when the only alternative for a couple saving for their first house was to scrimp for 20 years and then live further away than they want to when they buy a home. Many families now accept that if they want their children and perhaps even more importantly, their grandchildren, to have a good life, the older people will need to make a decent contribution. Where once it was common for grandparents to pay for school fees, the same now applies for homes.

It means a lot more planning. Parents may be approached by their children for financial assistance, and a big step is required on legal documentation. Living with multiple generations on one piece of suburban land will come with its challenges but will suit many.

With property increasingly scarce and demand outstripping supply, more people will need to face up to the decisions about living alternatives.

Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks.