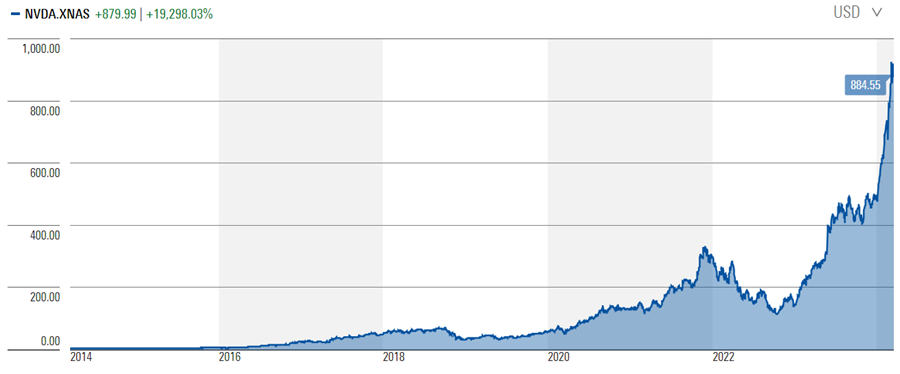

The holy grail of investing is to find a stock that can deliver life-changing returns. You don’t have to look far to see recent examples of companies that have achieved this feat. The chart of stock market darling, Nvidia, is something to behold.

Source: Morningstar

Over the past decade, Nvidia’s share price has increased 192x. In 2014, it was already a large company with a market capitalization of close to US$11.5 billion that few investors, barring institutions, had heard of. Now it’s worth US$2.2 trillion and everyone is talking about it.

There are examples in Australia too. Pro Medicus’ share price has risen 126x over the past 10 years. It’s grown from a small company with a market capitalization of close to $80 million into a top 50 ASX stock worth $10.1 billion.

Source: Morningstar

Some people see charts such as these and they invest in the market like they would the lottery – betting on a 1-in-a-million shot at hitting the next big thing. For instance, buying into a new technology, a new pharmaceutical drug, or a new mine. That kind of speculation often leads to poor results and disappointment.

What’s a better way of unearthing the next Nvidia or Pro Medicus? Here are four methods that can help find quality investments set to deliver strong long-term returns:

1. The Peter Lynch Way

Recently, Andrew Mitchell from Ophir Asset Management mentioned in a LinkedIn post that the one book he recommends to people who are new to investing is One Up on Wall Street by Peter Lynch. I agree.

Lynch is a former fund manager at Fidelity whose main fund returned 29% per annum from 1977 to 1990. He looked for growth stocks whose earnings were set to take off, and the book details how he identified these stocks.

One method still resonates with me. Lynch suggests investigating companies that you use every day. For example, you may own and run a small business. There’s a good chance that your accountant switched your accounting software to cloud provider, Xero, up to a decade ago. Back then, Xero wasn’t well known, and may have been worth exploring as an investment.

Taking the example further, you may operate this business in tourism and accommodation and know of other suppliers that are doing well. For instance, you might deal first-hand with Booking Group, which operates booking.com, and has been taking share from Expedia and others since Covid.

And your wife or children may come home one day raving about a new shop that offers a unique product or service. That could turn into the next Smiggle or Lovisa.

Lynch thinks that investors can get an edge by getting to know companies before they appear on the radars of institutional investors and brokers. And one way to do that is by keeping an eye on growing companies that you encounter in daily life.

2. The Warren Buffett way

When it comes to finding stocks that can deliver outsized long-term returns, there is no better teacher than Warren Buffett. In a recent article, Morningstar’s Amy Arnott, outlines the DNA of a typical Warren Buffett company. She sees five common traits of companies which make it into Buffett’s investment portfolio:

- An economic moat. This means a company that has a sustainable competitive advantage. For example, Berkshire Hathaway insurance subsidiary Geico enjoys a durable cost advantage by selling policies directly instead of paying sales reps.

- An outstanding management team. Buffett has always sought outstanding CEOs. He admired Katherine Graham, who ran The Washington Post in the 1970s, Tomy Murphy and Dan Burke at media outfit, Capital Cities/ABC, and Coca-Cola’s late Chairman Don Keogh.

- Thoughtful capital allocation. This means companies that deploy capital to build shareholder value over time. Buffett deplores empire building acquisitions, dilutive share raises, and managers who put themselves first rather than shareholders. Instead, he likes those businesses that make thoughtful acquisitions and buy back shares when their stocks are undervalued.

- Earnings power and financial strength. Buffett avoids companies that use accounting tricks to fudge their financial numbers. He prefers using measures such as operating earnings, return on equity, and free cashflow, to assess a company’s earnings power and strength. A famous example of earnings power comes from one of Buffett’s initial investments, in See’s Candies. Millions of repeat customers for its boxed chocolates and its low-cost structure means See’s has been able to consistently raise prices over time, enabling growing profits and returns on capital.

- An easy-to-understand business. Buffett has always favoured simple business models. For this reason, he shunned tech companies for a long time. He has also generally avoided rapidly evolving industries like airlines and investment banking.

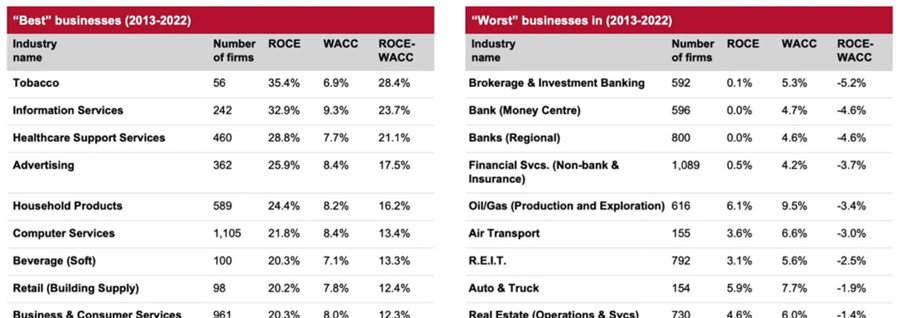

3. Find great companies in the best sectors

One shortcut to finding a Buffett-like stock is to identify the best and worst sectors to invest in. The best sectors are those that have a capacity to defy the laws of capitalism and retain high returns on capital over a long period of time. The below chart from finance professor, Aswath Damodaran, covers sectors in the US.

Source: Aswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at Stern School of Business at New York University.

Professor Damodaran aggregates each sector’s return on capital employed (ROCE), which measures how efficiently a company is using its capital to generate profits. And he also calculates the cost of capital (WACC) for the sectors. Companies create value whenever they can generate returns on capital above their WACCs. The higher the spread between ROCE and WACC, the better.

As the chart demonstrates, tobacco has created the most value of any sector in the US. It’s followed by the technology and healthcare sectors.

Conversely, the worst sectors to invest in are those that can’t generate returns above their costs of capital. Sectors in this category in the US include investment banking, banks, airlines, and oil gas.

The importance of the above is that higher ROCE-WACC spreads result in better long-term EPS growth, and higher share prices. It’s no coincidence that tobacco has been the best performing sector in the US over the past century.

While Professor Damodaran’s work focuses on the US market, it’s equally applicable to the ASX.

What allows an industry to produce high returns over a long time? It varies, though it can involve barriers to entry creating a consolidated industry. For tobacco, government restrictions on advertising favour incumbents as they make it hard for any new competitors to get traction with their brand. Increased taxes on smoking creates a further barrier for newer entrants to the industry.

Other consolidated sectors offering barriers to entry include payment networks with Visa and Mastercard, North American railroads, credit ratings with S&P Global and Moody’s.

Banking offers commoditized products, though the industry in Australia delivered outsized returns for a long time thanks to the government’s ‘four pillars’ policy. The sector’s structure is an oligopoly which has helped returns stay above the cost of capital.

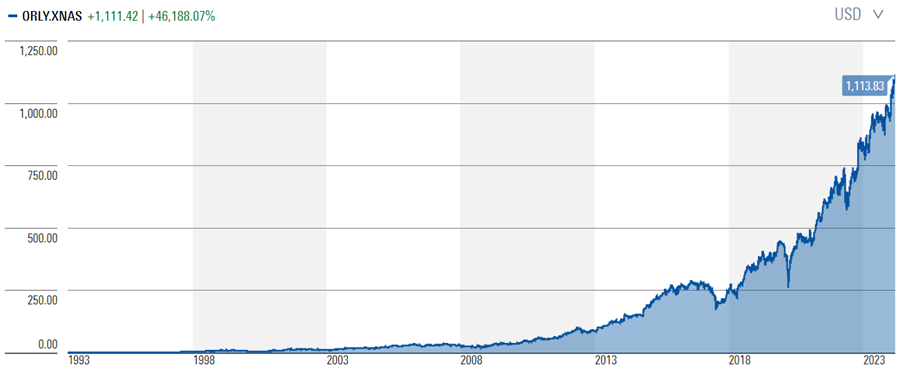

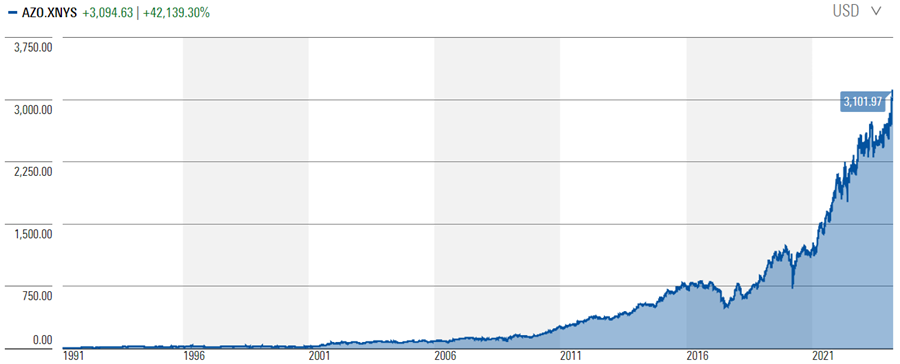

Some of the best investments have involved industries where there is slow growth, discouraging new competitors and encouraging consolidation. A great example of this is in US auto parts retailers, where O’Reilly Automotive and AutoZone have delivered spectacular long-term returns.

Source: Morningstar

Locally, examples of consolidating industries include insurance brokers, such as Steadfast and AUB, as well as funerals (Propel, and the formerly listed, InvoCare).

4. Linear stock prices

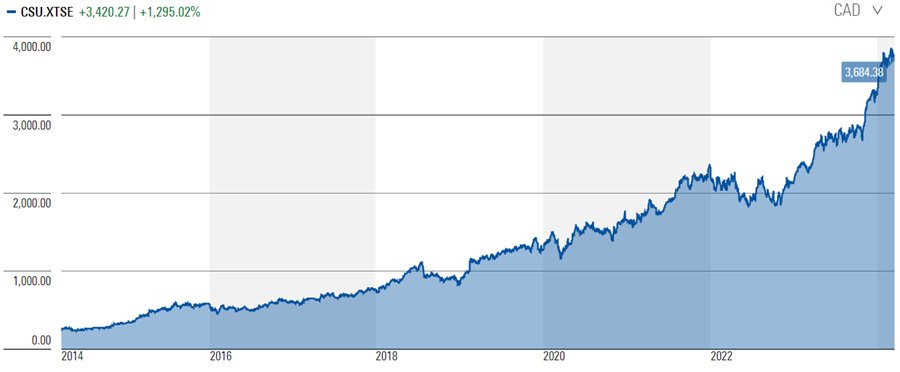

Recently, I came across a short book, The Intelligent Quality Investor, which looks at how to invest in the world’s best companies. The book focuses on the best stock performers of the past 40 years, and what they have in common. Besides the Buffett-like qualities of high returns on capital and prodigious free cashflow generation, the book also zeroes in on the concept of linearity. To illustrate the concept, let’s take the two charts below. The first is Constellation Software, a global software company, and the second is United States Steel.

Source: Morningstar

Linear charts are like the first one of Constellation Software. They go up and right and are relatively smooth. These types of charts often demonstrate companies that are consistently profitable, reinvest their profits at higher returns, and are resilient to economic downturns.

Non-linear charts such as United Steel’s, tend to show companies whose profits go up and down, are often capital-intensive, and are highly susceptible to recessions or downturns.

I would never suggest that price denotes value. However, the point here is that price charts can be a useful tool to identify quality companies.

Holding onto quality companies can be the hard part

It’s one thing to find the next Nvidia or Pro Medicus; it’s quite another to have the patience and conviction to hang onto a stock for the long haul and let compounding work its magic.

In his book, 100 Baggers, Chris Mayer says that the average US stock that’s gone up by 100x has taken 26 years to reach the milestone. 26 years on average.

Going back to the Nvidia chart at the beginning, despite the stock rising 192x over a shorter period of a decade, it still had multiple drawdowns, including when it dropped 65% in 2021-2022.

Few investors can withstand 65% stock price falls, and that may be the biggest lesson of all. As the late, great Charlie Munger once said: “if you can’t stomach 50% declines in your investment you will get the mediocre returns you deserve”.

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar