Affluent Australians usually hold their investments in some combination of superannuation, family trusts and direct ownership of negatively geared property. Over the last year, changes in superannuation rules and more challenging property market conditions have shifted the relative benefits of these arrangements. Family trusts have become comparatively more attractive. Investors should consider whether their 'structuring' and tax planning is still optimal.

The reduction in the income tax rate for small corporations, from 30% to 25%, will make the accumulation of wealth through family trusts more tax effective compared with super and negative gearing.

In the example below, a couple with children can accumulate wealth in their family trust at an effective tax rate of only 13.5% on their investment income. However, when the income tax on small corporations falls from 30% to 25%, as it is legislated to do, the same family trust’s strategy will accumulate wealth at an effective tax rate of only 11.3%.

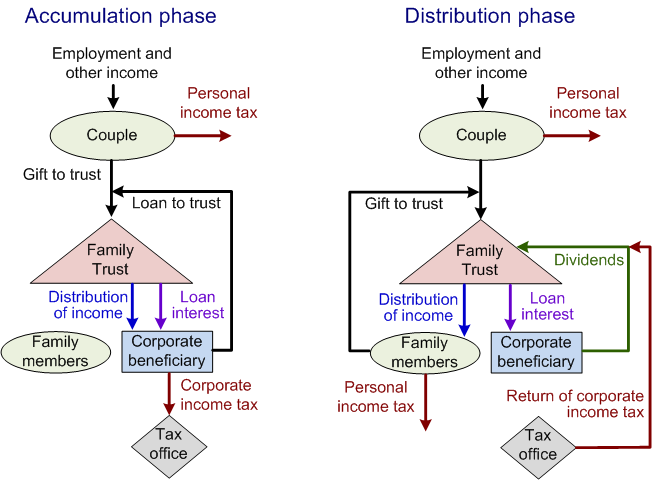

A family trust with a corporate beneficiary

Mei Li and Jack Houston are a professional couple with high incomes, with three young children aged two, four and six years. They recently sold an apartment that they bought a few years ago, and the couple decides to use the $200,000 net proceeds from the sale to establish a family trust.

The Houston Family Trust will have two purposes. The first and main purpose is to accumulate family wealth in a low tax environment. The second is asset protection (from law suits, creditors in bankruptcy, and some family situations).

After the Trust is 'settled' (brought into existence) the couple makes a gift of the $200,000 to the Trust (or they might instead have loaned the money to the Trust). The $200,000 is then invested in high-income assets, such as high-yielding shares or commercial property. The couple resolves to make further gifts of $20,000 at the beginning of each successive year from their after-tax income.

Six beneficiaries of the Trust are named in the Trust deed: Mei Li, Jack, each of their three children and a corporation (the corporate beneficiary).

Accumulation phase

Assume the pre-tax return on the Trust assets is 6.5% per year after adjusting for inflation, received entirely as income with no capital gain to simplify the example.

At the end of each year, the annual income from the Trust's assets must be distributed to the beneficiaries of the Trust. It will not be distributed to Mei Li or Jack because they already pay income tax at the highest rate. And, it cannot be distributed to the children (without incurring top rate income tax) until the children turn 18 years. So, in the first 12 years of the Trust's existence (until their eldest child turns 18), all of the income is distributed to the corporate beneficiary (CB), sometimes called a 'bucket company'.

The left-hand side of the diagram below shows the role of the corporate beneficiary in accumulating distributions from the Trust until the children are ready to receive distributions. Each year the CB receives the Trust income and pays corporate tax on that income. The payment of corporate tax creates credits for corporate tax paid (or franking credits).

At the end of the first year, there is $200,000 x 0.065 = $13,000 of Trust income, which is distributed to the CB. The CB then pays $13,000 x 0.30 = $3,900 of corporate income tax. The remaining $9,100 is loaned to the Trust. The CB then has assets of $9,100 (the loan) and $3,900 of franking credits.

At the end of the second year, the CB will again receive all the income generated by the assets of the Trust, but this time in two parts. First, as interest on the loan, and then the remainder as a simple distribution of income. The CB will again pay corporate income tax at the 30% rate and again loan its after tax income to the Trust.

And so it goes as 12 summers and 12 winters come and go. The children’s cartwheels on the backyard lawn turn to car wheels in the driveway, and now the eldest child reaches 18 years, and the Family Trust is now ready to move from accumulation to the distribution phase.

The cash flows in the accumulation and distribution phases

Distribution phase

After 11 years the totals are as follows:

- Gifts to the Trust have amounted to $420,000

- CB has stored $185,000 from accumulated income

- Tax paid of about $80,000.

At the end of the 12th year of the Trust's life, distributions to the CB cease and distributions to the children begin. Each child receives a distribution of $37,000 at the end of each year for six years after they turn 18. The children's after-tax income is then gifted back to the Trust. The distribution phase goes on for 10 years, with distributions peaking at $111,000 in the two years that all three children are receiving distributions.

The cash that is distributed to the children has three sources:

- Annual income from the Trust's assets, which is now distributed to the children instead of the CB.

- Value accumulated in the CB.

- Return of the corporate tax paid by the CB.

The diagram above shows on the right-hand side the cash flows in the distribution phase.

During the 10-year distribution phase, all the distributions to the CB that were made during the 12 years of the accumulation phase are returned to the Trust and distributed to the children. The value stored in the CB is paid to the Trust as a series of annual dividends (the Trust owns the shares in the CB). The Trust then passes the dividends, with franking credits attached, to the children who use the franking credits to reclaim the corporate tax that was paid. So, all the money that was ever sent to the CB, including the part that was then sent to the ATO as tax, is returned through the Trust to the children, who then pay personal income tax on that amount.

The Trust's 'effective' tax rate

At the end of the distribution phase the Trust has existed for 22 years. The accumulated value in the Trust is $1.38 million of which $620,000 is the gifts from the couple and $760,000 is the investment returns after tax. The Trust is now reset in the sense that the balance in the CB is zero and the tax credits are zero.

The couple can do whatever they wish with the $1.38 million, including taking it out of the Trust and paying it into their superannuation (at $100000 each per year); gifting it to the children to launch them in the property market; leaving it in the Trust and start accumulating again through the CB; or spending it.

The Family Trust provides some real tax benefits. The $620,000 of gifts compounded into the final value of $1.38 million at an annual rate of 5.62%, which is the after-tax return on the assets. The before-tax return is 6.50% and the after-tax return is 5.62%. Therefore, the effective tax rate of this strategy is 13.5%, which is less than the 15% income tax rate in superannuation during the accumulation phase.

The effective tax rate is so low because the income is stored in the CB until it can be retrieved and cycled through the children's income. When the children receive distributions of $37,000 they only pay $3,867 in income tax, which is an average tax rate of 10.5%.

But if the children pay all the tax (the CB's tax is all retrieved), then why isn't the effective tax rate of the strategy 10.5% instead of 13.5%? All the taxes paid by the CB are retrieved from the ATO and distributed to the children, but while the ATO has the CB's tax the ATO is effectively receiving a zero-interest loan from the Trust. The ATO does not receive a loan in a legal sense, but that is how we should think of it economically. The taxes go to the ATO but are only returned after a period of time, and that raises the effective tax rate of the strategy.

Effect of corporate tax falling from 30% to 25%

The effect of the tax on small corporations (< $10 million in income) slowly falling from 30% to 25% will lead to the Trust having $1.41 million in assets after 22 years and the effective tax rate falls to 11.3%.

The effective Trust tax rate is lower when the corporate tax rate falls, even though all corporate tax is returned because the corporate tax rate determines the size of the zero-interest loan to the ATO. If the corporate tax rate is 30% then the ATO has collected about $79,000 of corporate tax during the accumulation phase (the size of the zero-interest loan). If the tax rate is only 25% then the accumulated tax is $67,000.

If there were no delay in the return of tax paid, through franking credits, then it would not matter to the couple whether the corporate tax rate was 30% or 25%. But once there is a delay in return then the tax becomes a zero-interest loan to the ATO, until it is returned. If that loan goes on forever, then the effective tax rate equals the corporate tax rate of 30%.

A CB meets the ATO's requirement that a corporation is carrying on a business to qualify for the lower tax rate on small businesses, as according to ATO's website, even if the company's activities are relatively passive, and its activities consist of receiving rents or returns on its investments and distributing them to shareholders.

Dr. Sam Wylie is a Principal Fellow of the Melbourne Business School and a Director of Windlestone Education. Sam consults and teaches finance programmes for corporate and government clients. Please seek professional advice on structuring and tax planning from a qualified accountant or financial planner. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.