Graeme Shaw is a Director at Orbis Investments and has worked at Orbis as an Investment Analyst on global equities since 1997.

GH: Orbis’s contrarian investing approach is a difficult style of management and as your own website says, you often find “boring, overlooked and even hated companies”. What are the challenges and does it require a certain personality to invest this way?

GS: Yes it does. You're often buying things that other people say are terrible. The brokers don't like them, your own clients might look at you like you're a little bit mad and they start questioning whether they should have hired you. Society conspires to make you feel like you've done something wrong.

You need to have an independence about the way you think and a willingness to analyse the evidence and come to a fact-based decision on what a company is worth, rather than getting caught up in the emotion.

GH: And just because it's unloved doesn't mean that you can pick the low point, so you can still have pain buying a cheap stock.

GS: Absolutely. Look at Simon Mawhinney from Allan Gray.

GH: Yes, he’s been toughing it out holding AMP.

GS: The team at Allan Gray has observed that there are two differences between our style and other value-oriented investors. One is we buy the stocks that are so uncomfortable to own that even the analysts recommending them feel uncomfortable. And second, when others buy a stock and it's gone down a lot, they come under a lot of pressure to sell and absolutely not buy more. History shows that a large part of our outperformance comes from those two categories.

GH: Is there an uncomfortable stock that you've bought in the last few months.

GS: BMW. It was already cheap along with most other global automakers on the fear that electric cars will disrupt the industry or that self-driving cars means nobody needs to own a car again. Then when coronavirus hit, nobody wanted to own a company that sells expensive cars to rich people. We spent a lot of time with the company. We calculated BMW could shut down all its factories, tell its staff not to come to work but continue paying them and not sell any new cars for about a year and a half before they would need to tap the debt markets. It’s a resilient business that gives us confidence it will ride out this pandemic well.

GH: Has that thesis played out yet?

GS: It’s well off its lows, especially since people are nervous about catching public transport or using Uber. Owning a car is something many urban dwellers decided they needed to do for the first time. Plus, China has dealt with the pandemic and its car sales are growing again and that's a big market for BMW. Many people have tried to break into the luxury car market, mostly unsuccessfully, leaving the market to Audi and Mercedes and BMW with high barriers to entry and good margins.

GH: Looking long term at your Global Equity Strategy Fund, the numbers are good, but more recently, it has struggled. Is this the ‘value versus growth’ story?

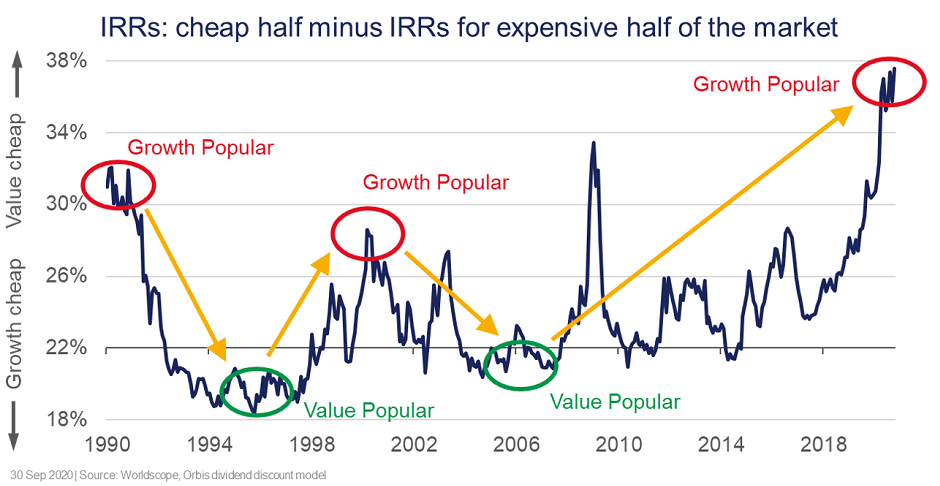

GS: That’s a big part of why the last three years have been tough. If you go back to 2006, value had been doing well for years after the tech bubble burst in 2000. In 2006, everyone wanted to be a value manager. It wasn’t ‘growth’, it was ‘growth at a reasonable price’.

GH. Ah yes, I remember the old GARP, you don’t hear that much these days.

GS: And in 2006, we were finding high quality growth stocks that were very attractive, such as Microsoft and Cisco and Google. We were picking up those companies on P/Es of 10 to 12 and yet the more cyclical, value-oriented companies were not cheap and many of them were expensive. So, in 2007, there was a strong signal from the market that it was a really good time to be a growth/quality investor as the gap in valuation between growth and value was near the bottom of it historical range.

Look at that same valuation metric today using something simple like the ratio of price to book or price to sales. Whichever way you slice and dice the data, the valuation gap between value and growth is historically incredibly wide. It’s the most extreme period for value investing in 200 years, according to a recent FT article.

Here's a graph showing the difference in expected returns between the cheaper, more value-oriented stocks and the more expensive, growth-oriented stocks, calculated over time using a dividend discount model. There are periods where growth stocks are relatively cheap and other periods where value stocks are relatively cheap. The style that has done well becomes more popular at points in the cycle. A contrarian approach to the weighting of value and growth makes sense.

Some people will say value investing is broken but it can never be broken. You outperform in the stockmarket, which is a zero-sum game before costs, when somebody else makes the mistake of selling you a stock too cheaply and therefore they underperform. What type of mistakes do people make? Well, they make all the usual human ones. When things are bad, they get emotional, they get pessimistic, they give up. They want to deal with their mistakes by selling them so they don’t have to look at them anymore.

And all of those characteristics are still true, and vice versa when something's going really well, they get over optimistic, they get emotional, they start cheering for Team Amazon ...

GH: Or in Australia, Team BNPL.

GS: And they only look at the good news and they ignore the bad news and they push it and overpay, and human beings haven't changed. If you look at the last 13 years, growth stocks had great valuations in 2007 and it was definitely a good time to be a growth manager. And then for a decade, many of those growth companies genuinely added value and deserved to go up. These are the Amazons and Facebooks and Apples of this world - high-quality businesses with great cash flow, high barriers to entry.

But if you look in the last three years, the multiples applied to those businesses have expanded much faster than the underlying earnings. That's where a lot of the overvaluation has come from as everyone gets over excited and things start getting silly and that's what's happened.

GH: So you’ve owned those stocks in the past but you've exited in recent years?

GS: Yes. If you look at this what people call the FANGAMs to include Microsoft, they’re about 15% of the MSCI World Index and we have about 3% in those stocks, predominantly Facebook and a little bit of Google. We struggle to find value but they're not ‘tech bubble crazy’. We’d be happy to own more if they fell by 50% whereas in the tech bubble, there were plenty of stocks that we didn’t want if they fell 90%. They were not good businesses.

But we also avoided the fall out in retail. We knew online would be the dominant format so we stayed away from most of those value traps in the traditional retailers. In the past, we owned Rakuten in Japan, which is the dominant online retailer and MercadoLibre in South America, we have owned Amazon twice and we owned PayPal. But at some point, these stocks reached valuations where we could find better places to put money. Today we are seeing a scenario where a lot of tech companies are trading on FANG-like multiples even though it is unlikely their businesses will be as successful. We call them ‘imitation valuations without imitation businesses’.

GH: And on the other side, what are some sectors or companies that look cheap?

GS: The market tends to look back at the last war where companies have done well off the expansion of smartphones or online, but what’s the key theme for the next 10 years?

Green energy could be one. We’ve had a good look at solar power, but there’s over-capacity and too much competition. We like the world's largest maker of wind turbines, Vestas, as wind power has become low cost and doesn't require subsidies. Even if the world leaves all its all its hydrocarbon burning generation in place but only grows new generation through green initiatives, then that alone is enough for solar and wind to grow massively. A Biden win is a bonus. Vestas is a company whose economic profits are higher than its accounting profits, because its accounting profits reflect service contracts signed in the past, whereas economic profits are new wind turbine sales plus new service contracts. It's cheaper than it looks with multi decades of growth.

GH: What are your three favorite stocks at the moment?

GS: If I look at the top five stocks in the fund, there are three I'd highlight. BMW is on about five times its normal earnings capability. Typically, it trades at more than 10 times so BMW is at half price. People look at Tesla but BMW has a huge number of electric vehicles and hybrids coming out. We like hybrids because it makes more sense for a large number of people to have a small battery that does 60 kilometres then kicks into a small petrol engine rather than a small number of people having a large, expensive battery in an all-electric car. Hybrids are cheaper to make so people can afford to buy them, unlike Teslas.

The market makes the mistake of dismissing value stocks as low quality. But the higher quality value names include Anthem, a US health insurance company. It's operating an oligopoly, it's a business the US can't do without as it sits in the middle of the healthcare system and coordinates everything. If someone gets sick they manage the relationship with the hospitals and with the drug companies. An oligopoly priced at 12 times earnings and its earnings have grown faster than the market historically.

And a third one is Naspers which is a way of buying TenCent at a discount. While Naspers is a South African company, its biggest asset is a stake in TenCent. The price of Naspers is so low relative to TenCent that it allows you to buy China's best internet company at half price.

We also like a Chinese online gaming company called NetEase. If you strip out the cash on its balance sheet and the losses in its startup businesses, it's only trading at around 19 times core earnings, so a similar P/E to the market while it is growing much quicker. These entrepreneurial companies often include many start-ups under one umbrella and the losses of the start-ups can hide high much higher profits and free cash flow in the core business.

GH: What's your biggest portfolio disappointment?

GS: We sold our FANG stocks too soon. We’ve also been surprised how low value stocks have gone. For example Japan has stocks trading at 4% to 6% dividend yields, solid businesses such as KDDI, a Japanese mobile phone operator. They've never missed a dividend in 20 years, they've grown at a reasonable rate and they’re well managed. A lot of these companies have low payout ratios so they can grow their dividends simply by raising their payout ratios from the low 30s to 50s. Warren Buffett recently bought a basket of Japanese trading companies.

GH: Why do you only have one Australian stock, Newcrest, in your global portfolio?

GS: The general reason is that Australia represents only 2%-3% of global opportunities. There are about 5,000 stocks we can buy, and historically, about 15% of them beat the market by 10% or more. So that means 750 stocks we would be happy to own and we need 50 of them. There are thus always a lot of good stocks that we don't buy. So if we miss out on Australia, it’s because we have found something a bit better or a bit safer. We do like Alumina as it looks incredibly cheap and the world will always want aluminium.

GH: What’s the biggest investment theme on your mind at the moment?

GS: It’s recognising where we are in the long span of investing. I think we are at a very unusual fringe point. Investors should take care believing in many of the things they believed in the past. For example, I'm not a huge fan of balanced funds, but if ever there was a time to spread things out and diversify widely, this is one of those times. Spread investments across different equity management styles and different asset classes and don’t expect the growth style to continue forever.

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. Graeme Shaw is a Director at Orbis Investment and has worked at Orbis as an investment analyst since 1997. Orbis is a sponsor of Firstlinks.

This report contains general information only and not personal financial or investment advice. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or individual needs of any particular person.