The Federal Government’s latest fiscal stimulus programme centred around a wage subsidy to help combat the impact on the economy of coronavirus-driven shutdowns has generated much community support.

But how will it be paid for? Can we afford it? How does RBA quantitative easing fit into it? And what are the longer-term consequences in terms of inflation and debt?

A rise in public debt of half a trillion

These are valid questions given that together with the previous two fiscal stimulus packages it will add dramatically to Federal Government’s budget deficit – by around $200 billion over the next year (or about 10% of GDP). And to this needs to be added the hit to public revenue from the economic downturn we are now in. So the total rise in public debt could be $500 billion or so (or about 25% of GDP).

To the question of how it will be paid for the answer is simple: the Government will issue bonds and borrow the money required.

However, there are several things to say on all this.

First, it’s absolutely necessary. In normal circumstances, such a massive public stimulus program and boost to public debt - which is nearly double what we saw in the GFC – could not be justified. But these are not normal times. The hit to economic activity in Australia from the shutdowns could be 10% to 15% of GDP. This requires a similarly-sized stimulus programme to offset it, otherwise we risk doing immeasurable collateral damage to the economy. It will take much longer to recover from such damage, ultimately resulting in an even bigger hit to the budget.

Second, to borrow from classic Keynesian economics, it makes sense for the public sector to borrow from households and businesses at a time when they are stuck at home and can’t spend. Government spending the borrowed funds helps smooth out the economy.

Sure the stimulus won’t stop the virus or spur immediate spending when people are locked up inside but it will help support businesses and household income. Then they can survive this period of hibernation and hopefully bounce back once it comes to an end. The trick for the Federal Government is to curtail the stimulus and its borrowing once the economy bounces back and the private sector starts to borrow again otherwise the competition for funds will boost interest rates and create problems for the economy.

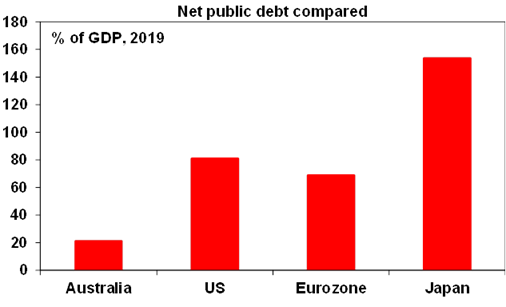

Third, Australia’s public debt is far lower than in other comparable countries. In fact, net public debt as a share of GDP is around a quarter of what it is in comparable advanced economies. See the next chart. So Australia has far greater scope to undertake fiscal stimulus than other comparable countries.

Source: IMF, AMP Capital

Fourth, the cost of borrowing for the Federal Government right now is very low at just 0.25% for three years and 0.75% for 10 years. So it’s not as if the Federal Government is incurring a huge interest bill or ‘crowding out’ private sector borrowing or investment.

Finally, the budget blowout may risk a downgrade in Australia’s AAA sovereign debt rating, but ratings are a bit of a relative game and Australia’s public finances will still look relatively better than others. I would rather a rating downgrade than a deep depression/recession any day … particularly when any downgrade will have no impact on the Federal Government’s cost of borrowing!

How does RBA quantitative easing fit into all this?

The RBA is using printed money to buy government bonds in order to help keep interest rates down. It’s buying these bonds in the secondary market (eg from fund managers) so it’s not directly providing the money to the Government and those bonds still have to be paid back when they mature. So it’s not really ‘helicopter money’, which would see the RBA print money and give it to the Government which it would then spend. But it is aiding the process by helping to keep bond yields down.

In the meantime, the balance sheet of the RBA will rise as it holds more bonds but this is not a major issue unless inflation starts to rise due to all the extra printed money in the system. The Fed, ECB and Bank of Japan have been expanding their balance sheets through QE for years now with no rise in inflation so the RBA presumably has a long way to go in this process before it becomes a problem. In fact if the Fed and others had not been doing QE, their countries would probably be mired in deflation by now. Put simply, there is no magical right or wrong for the level of the RBA’s balance sheet.

Longer-term consequences

When the dust settles, Australia will be left with much higher public debt at maybe around 45-50% of GDP in net terms but this will still be below that in other comparable countries. And it will be the price we paid to (hopefully) minimise the loss of life from the virus and at the same time minimise the hit to people’s livelihoods from the shutdown.

This may necessitate forgoing the next round of tax cuts due in 2022 or imposition of a new deficit levy at some point. And it may put a burden on future generations much as Government spending to fund the war effort in WW2 did. But I reckon that’s a cost most Australian’s are prepared to bear given that not acting now with public support mechanisms would likely lead to a far worse outcome.

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP Capital, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from AMP Capital, click here.