[Let’s deal with the disclosures upfront. Magellan Asset Management is a sponsor of Cuffelinks, and Chris Cuffe and I have known the principals since well before Magellan started. Magellan recently celebrated its 10th anniversary, but I don’t want this to read as a ‘puff piece’. It’s an insight into the early struggles and how to build an asset management powerhouse in a decade].

----------

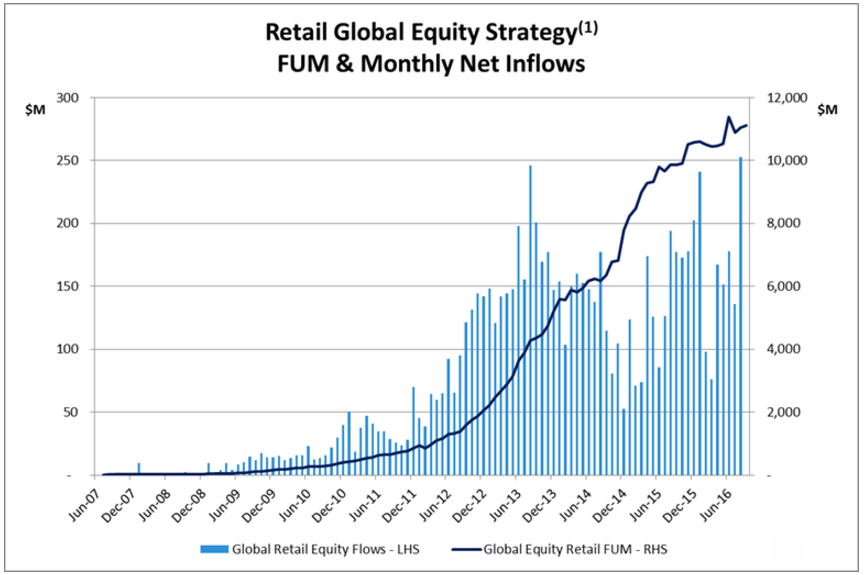

Magellan was established in September 2006, and its funds under management (FUM) did not reach $1 billion until April 2010. By September 2016, it held $42 billion. It kickstarted the business with a Listed Investment Company (LIC) raising $378 million in December 2006, driven by the market contacts of Hamish Douglass and Chris Mackay from their investment banking days. The LIC proved critical to give an underlying earnings base while the unlisted funds grew slowly, especially when the GFC hit in 2008. As shown below, Magellan did not establish a meaningful reputation among advisers and retail investors until 2010, and confidence in equity investments after the GFC took time to recover. In fact, the GFC came early enough in the history of their open-ended funds that they had little FUM there, and so Magellan faced far less of the redemption problems of larger players.

retail-global-equity-strategy-magellan-281016

Slow start while engaging gatekeepers

Other than the LIC market, the opportunities for fund managers to directly access retail investors in 2006 were scarce, requiring a business to build relationships with financial advisers, researchers and well-established platforms. For the first few years, this meant Hamish Douglass and Head of Distribution, Frank Casarotti, wore out the shoe leather meeting the major platform providers such as BT, Colonial First State (CFS) and AMP, and adviser groups both big and small.

For example, every fund manager wants to be on CFS’s FirstChoice, as it is used by thousands of CBA-aligned and independent advisers. But it has a limited menu, and CEO Brian Bissaker was not interested initially in an unproven fund run by a couple of investment bankers. Says Bissaker:

“The issue with putting them on our main platform when they first set up was that FirstChoice was 100% mandates which was its competitive advantage and every new mandate required seeding from CBA capital. We could not in all conscience put bank capital into a fund where the two managers, although highly experienced and respected investment bankers, had no funds management experience. That’s why we wanted to see at least three years of track record.”

And so Douglass and Casarotti waited years until Bissaker opened the door, and it was the same across the other major platforms. Magellan did not have a month of retail flows over $50 million until 2012, but they never stopped making the calls, drinking the bad coffee, presenting wherever possible and telling the Magellan story. They needed to build a performance record, dealer group inclusion on approved product lists, researcher ratings and appetite in the retail market first.

“It was not until somewhere between years 3 and 4 when we looked at the timing of new product releases, agreed the commercial arrangements and showed the demand we had generated, and it was year 4 before we were added to the major platforms,” says Casarotti. “Now we have about $1.4 billion on FirstChoice alone.”

A differentiated global offer

In 2006, retail global equity portfolios in Australia were dominated by Platinum. Magellan thought their investment style would at least complement Kerr Neilson, who had done a trailblazing job. An early discipline was to be ‘ex-resources’, since most local investors were probably overweight resources already. The investment discipline focussed on identifying outstanding companies and sectors especially relevant to Australian investors, such as emerging market or industries not well-represented on the ASX. For example, they promoted emerging markets exposure by investing in the big US companies like Microsoft, Proctor & Gamble, Visa and eBay who were selling goods and services in Asia and South America. There was no equivalent on the ASX. To this day, they look at where the revenues are earned, not the company’s country of domicile.

Magellan built its investment team to about 15 relatively quickly (it now has 36 among staff of 101), and was able to cover global equities by screening the universe to less than 200 names, from which 25 made the portfolio. They had good access to overseas companies even when they were small, because they had the novelty of coming from Australia. Hamish and Chris used their investment banking background to delve into different types of insights than many other asset managers who studied the financials.

Magellan also set an unusual absolute target of 9% rather than the more common ‘index plus’. The global fund held up reasonably well in the GFC, aided by the declining currency, but the early days of the infrastructure fund were difficult, as they were underweight utilities, which held up the best, but more overweight on transport infrastructure which lost more heavily. They ground through the GFC, meeting with anyone who wanted to discuss the portfolio. Coming out the other side, especially once it was clear the central banks would prime the system, the big US companies with global brands and distribution recovered strongly, and performance kicked in well.

Money starts to flow in

Casarotti remembers one meeting in Christchurch at an outdoor café, just coming out of the GFC, and a NZ adviser said they would be moving $9 million across to their fund. Casarotti kicked Douglass under the table, because for many months, they’d only been seeing parcels of $5,000 to $10,000. He recalls opening the spreadsheet of applications from the administrator and it was empty most days. This NZ experience was a massive moment, and similarly, the first $100 million inflow month felt like a major milestone.

When dealer groups asked Magellan to sponsor conferences, Casarotti pushed back, saying they wanted to see the deal flows first. It was a time when rebates paid to dealer groups were common and Magellan did not play the game. There was an institutional price for large parcels with a base fee of around 0.8%, while both the listed and unlisted retail fund have a base fee of 1.35% (plus performance fees) for global equities.

The first big institutional win was into ‘proprietary passive’ by the infrastructure team, and a large global equity mandate out of the UK from St James's Place pushed the FUM from $3 billion to $5 billion. The distribution partnership formed with Frontier Partners in August 2011 in the US has introduced around $9 billion from a who’s who of investors.

In 2014, Magellan was 8% under a strong global index return of 20%, and about 4,500 advisers were using their funds. Casarotti recalls only eight phone calls. He feels the reason there was so little complaining was that Douglass had communicated their strategy continuously to the market, they were achieving the 9% target, and underperformance was generally due to the strength of resources and mid-caps, which Magellan did not hold. While new inflows slowed, redemptions were modest, and applications picked up again with better performance.

Where the business stands today

As at 30 September 2016, Magellan held total FUM over $42 billion. Of this, $12.6 billion is retail and $29.7 billion from institutions (Australia/NZ $4.5 billion, US $9.6 billion, ROW $15.6 billion). Total in global equities $35.4 billion, infrastructure equities $6.9 billion.

To this day, the direct-to-retail business is only about 5% of unlisted funds, and even the listed vehicles have a lot of adviser input. Going direct does not have a price advantage for the investor.

During the GFC, the company’s share price hit a low of 33 cents (2 March 2009), although the business held about 90 cents per share of cash. It shows the severity of the market panic. Based on an investment in the recapitalisation in May 2007 at $0.975 per share, assuming dividends are reinvested, an investment of $1,000 then would be worth about $26,000 today, and the share price has been above $28.

Graham Hand is Editor of Cuffelinks and owns shares in Magellan through his SMSF.