This article is based on edited extracts from Paul Tilley’s book, Mixed Fortunes: A History of Tax Reform in Australia, published by MUP https://www.mup.com.au/books/mixed-fortunes-paperback-softback.

-----

A country’s tax system has a quasi-constitutional character in that it establishes how a community shares the burden of funding government services and substantially remains in force over long periods. Major tax reform exercises, therefore, should be few and far between. On occasion, though, a government needs to fundamentally rethink aspects of its tax structure which have become flawed or outdated. We now face one of those occasions.

Australia’s tax reform fortunes, though, have been mixed. While there have been numerous tax reviews at the Commonwealth and state levels, most have not resulted directly in substantive tax reforms. This two-part series looks at that history and explores the pathway forward. Part one will look at the history of the Australian tax system and the issues it now confronts. Part two will look at specific tax reform episodes and contemplate ‘where to from here’.

Development of the Australian tax system since Federation

At Federation in 1901, the newly formed Commonwealth Government was given exclusive constitutional access to customs and excise. The Commonwealth subsequently used its dominant constitutional and economic position to also monopolise broad-based income and consumption taxes, leaving the states and territories with an eclectic mix of taxes, including payroll tax, stamp duties and land tax, most of which suffer from design flaws accentuated by interstate competition.

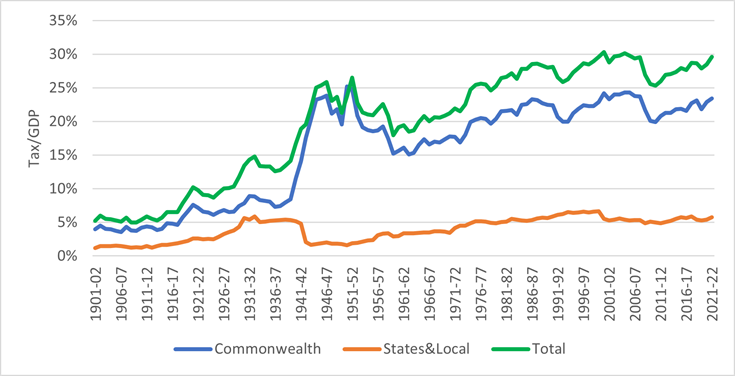

The development of the Australian tax system has featured a ratcheting up of the tax take in times of crisis. As Chart 1 shows, from around 5% of GDP at Federation, the tax burden stepped up in WW1, the Great Depression, and WW2. It then increased steadily in the post-war period to 25-30% by the 1980s, and has been around that level since.

Chart 1: Tax/GDP since Federation

Commonwealth tax mix

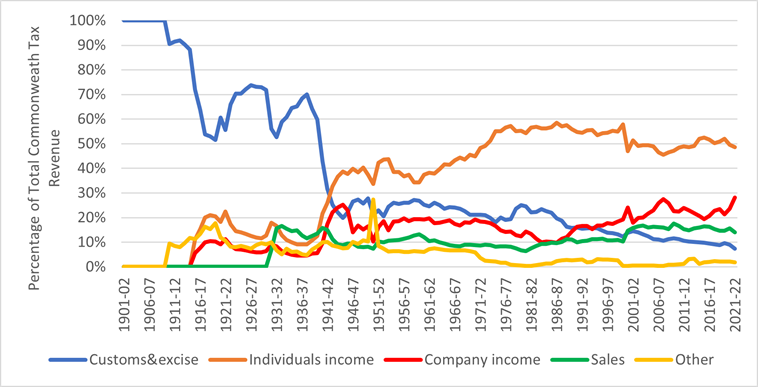

The main driver of these changes has been income tax. Chart 2 shows the transition at the Commonwealth level from an initial reliance on customs and excise duties to income taxes. A striking feature of this chart is that individuals' income tax has been broadly steady at around half of total Commonwealth tax revenue for the past 50 years.

Chart 2: Tax Mix since Federation (Commonwealth)

State tax mix

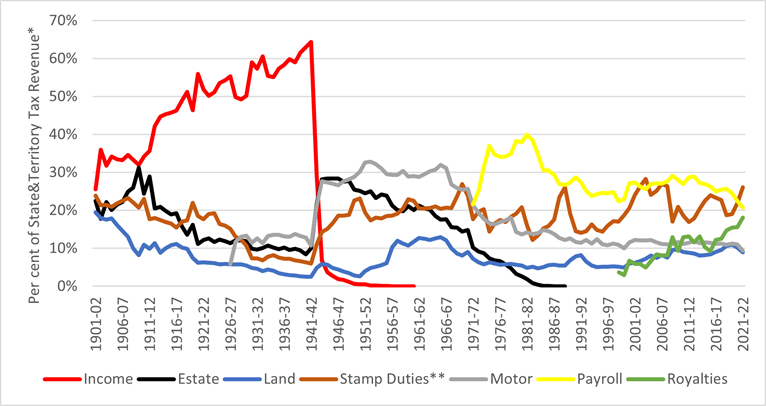

The Commonwealth dominance of income taxes and broad-based consumption taxes left the states and territories with an eclectic mix of other taxes. As Chart 3 shows, after the Commonwealth forced the states out of income tax, they have been reliant on a collection of limited tax bases. Payroll tax and stamp duties now dominate, with royalties also important for some states.

Chart 3: Tax Mix since Federation (States and Territories)

International comparison

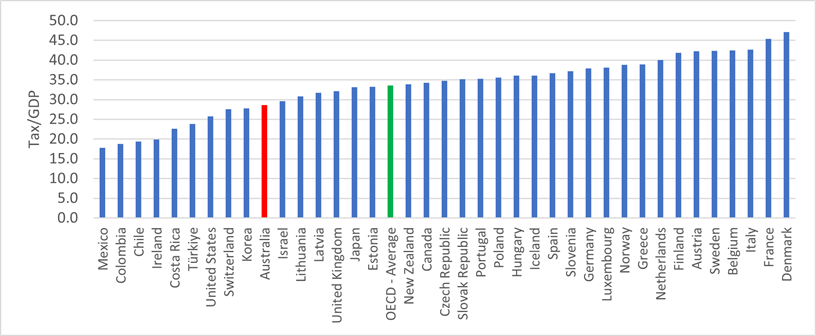

As Chart 4 shows, Australia’s overall tax burden is lower than the OECD average. This observation needs to be tempered, though, by the nature of Australia’s Superannuation Guarantee payments which are private, but given the compulsory contribution and preservation requirements they have some similarity to the European-style social security payments which are classified as taxes.

Chart 4: Total Tax Revenue as a Proportion of GDP, OECD Countries, 2020

Australia has a higher proportion of income taxes in its tax mix than most OECD countries, although this observation also needs to be tempered by the non-inclusion of social security contributions in that measure which make up a quarter of total tax revenue on average in OECD countries.

Assessment of the Australian tax system

Aspects of Australia’s taxes remain arcane and sorely in need of reform. A real estate agent would describe the Australian tax system as a renovator’s delight. We are not well positioned for the challenges that lie ahead, including the possible need to increase the overall tax burden in the face of large spending pressures in areas such as disability support, age care, health and defence.

At the Commonwealth level, the heavy reliance on personal income tax is problematic as an aging population means future generations of workers will need to shoulder an increased burden, with worrying intergenerational equity consequences. Ken Henry refers to this as an intergenerational tragedy of our own making. Likewise, the future of the company income tax system warrants reconsideration in a world where the cost of capital is set in international markets.

At the state level, the continued use of outdated and inefficient transaction taxes creates economic disincentives and impediments, while potentially efficient tax bases, such as land and payrolls, are in need of repair.

Income taxes

Individuals' income tax remains Australia’s largest tax and the one that most fully meets the general tax policy criteria of revenue adequacy, efficiency, equity and simplicity. That said, there are several potential reform issues.

Individuals' income tax is broadly based for labour income but provides some significant concessions and inconsistencies in the taxation of savings vehicles, such as superannuation, housing and capital gains generally. These tax concessions generally favour higher income individuals with concerning equity implications. Other issues include the work disincentive effects of high effective marginal tax rates that result from the interactions with the transfer system, and the ever-present bracket creep.

Company income tax is vulnerable in the global economy in which large businesses substantially operate. Australia’s company tax rate of 30% is high by international standards, raising questions about the implications for attracting internationally mobile foreign capital. However, it is also significantly below the top individuals' income tax rate of 47% (even more so for smaller companies with a 25% rate), creating opportunities for tax avoidance practices.

Going forward, with company income tax vulnerable and other tax bases either inefficient or constrained in various ways, increased weight will likely fall on personal income tax levied on future generations of workers. Thus, the intergenerational inequity on a large scale.

Rent taxes

Taxes on economic rents are relatively efficient, as by only applying above the normal rate of return they should not influence investment decisions. While resource rent taxes have a difficult history in Australia, more consistent resource rent tax arrangement in the Federation, possibly replacing existing royalty arrangements, is an obvious area of focus for a future tax reform exercise.

Goods and services tax

Australia’s GST is levied by the Commonwealth using its constitutional power, but with the revenue passed to the states. The Australian GST, though, applies to only half of consumption and operates at a significantly lower rate than most OECD countries, presenting obvious reform opportunities.

While GST reform options are constrained by equity considerations, an increased GST rate could replace further inefficient state taxes such as the remaining stamp duties. The requirement for all nine governments to agree on any changes to the GST, though, makes reform politically difficult.

Excise duties

Australia’s system of excise duties applies additional taxation to areas of consumption with substantial externalities or other public good characteristics, in particular the so-called ‘sin’ taxes on tobacco, alcohol and petrol.

Fuel excise warrants consideration, though, with the switch to electric vehicles requiring consideration of how to charge for congestion and road use/damage aspects. A broad system of road-user charges may ultimately be necessary.

Payroll tax

A broad-based payroll tax is relatively efficient, with similar incidence to a broad-based consumption tax. The state payroll taxes, though, have substantial exemptions for smaller businesses which narrow the bases, compromising their efficiency. While governments have not been prepared to extend payroll tax to smaller businesses, there have been successful efforts to harmonise aspects of the payroll tax bases and definitions between jurisdictions.

Stamp duties

Stamp duties are generally considered to be relatively inefficient transaction taxes and considerable efforts have been made to remove them over recent decades. The remaining stamp duties continue to raise substantial revenue, however, and so further reductions or removal will require the identification of alternative revenue sources.

The largest, and most contentious, remaining stamp duty is on property conveyances. It is a volatile source of revenue and a disincentive to housing turnover, thus acting as a restraint on mobility and an inequitable impost on individuals who do need to move more often. A tax mix switch from conveyance duty to land tax, preferably broad-based, is therefore an obvious reform direction.

Land tax

A broad-based land tax is a potentially efficient tax given the immobility of land. The existing state land taxes are generally levied at progressive rates on unimproved land values, but with exemptions for owner-occupied housing and primary production land. Levying the taxes on unimproved land avoids creating a disincentive for development, but the progressive rates discriminate against larger parcels of land.

Property rates

Property rates are applied by local governments, under delegated authority from state governments, as a broad-based land tax. They have been assessed as Australia’s most efficient tax and are well suited to funding local government services.

Where to?

With so many fundamental tax reform issues across the federation to address it is hard to know where to start. Incremental reform efforts have failed to make major in-roads, and indeed at times have gone backwards.

A major tax reform exercise would require the commissioning of a formal tax review. This approach has underpinned the major tax reform packages that Australia has achieved in the past. The three most notable of those are the Curtin government’s 1942 income tax unification, the Hawke government’s 1985 income tax base–broadening package, and the Howard government’s 2000 consumption tax base–broadening package. Sadly, though, many other tax reviews have only delivered partial reforms, at best.

Part two of this series will look at the main tax reviews Australia has undertaken and explore the question of what are the key ingredients that make a tax reform exercise work, or not.

This article is based on edited extracts from Paul Tilley’s book, Mixed Fortunes: A History of Tax Reform in Australia, published by MUP https://www.mup.com.au/books/mixed-fortunes-paperback-softback.

Paul Tilley was an economic policy adviser to governments for thirty years, working mainly in Treasury but also the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasurer’s Office, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. He is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, and a Senior Fellow at the Melbourne Law School.