The financial services industry may have underestimated the dramatic fall-off in retiree spending as retirees age, according to our analysis of real-world expenditure data. This is potentially a positive message for retirees and their advisers dealing with the Covid-19 crisis.

How retirement spending falls

The median retired couple’s expenditure falls by more than one-third (36.7%) as they move from their peak spending years in early retirement (65 to 69 years-of-age) and into older age (85 years and beyond). The decline in expenditure for couples is relatively stable in the early years of retirement at about 6% to 8% across each four-year age band, but then rapidly accelerates once retirees pass 80 years-of-age.

Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) has previously estimated a ‘comfortable’ couple aged 85+ years will spend about 8% less than those aged 65-85 years of age. Another industry study by the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees (AIST), based on Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data, has suggested that spending may not decline materially through retirement.

However, the Milliman Retirement Expectations and Spending Profiles (ESP) analysis is the first based on the actual spending of more than 300,000 Australian retirees.

The data shows that retirees’ food expenditure—the largest component of essential spending—declines steeply with age, while health spending increases with age but dips again after age 80. All discretionary expenditure, such as travel and leisure, declines throughout retirement.

The faster-than-expected drop-off in spending casts doubt on some common rules of thumb and suggests that financial plans for retirees that assume a steady or increasing spending over time may be conservative relative to actual behaviour. This is potentially good news for advisers and their clients given recent events.

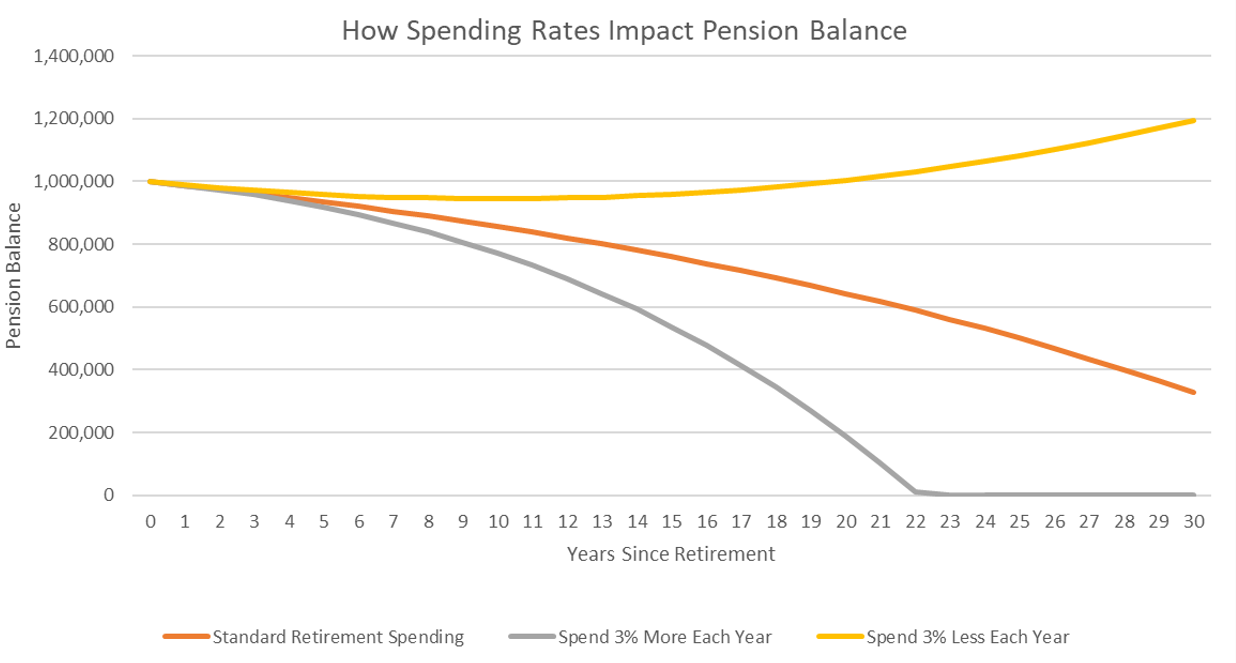

If we compare a small increase of 3% each year in a $50,000 p.a. retirement spend with an equivalent decrease of 3%, we find that this change has massive implications on retirement account balances (Figure 1). In fact, in the scenario where spending decreases annually, retirees can end up with a higher account balance than when they first retired, due to underlying asset growth outstripping spending.

Even assuming no annual increase in spending results in a drastically different picture that can help to offset the concern of seeing a drop in asset values as a result of market volatility.

Figure 1: How spending rates impact pension balance

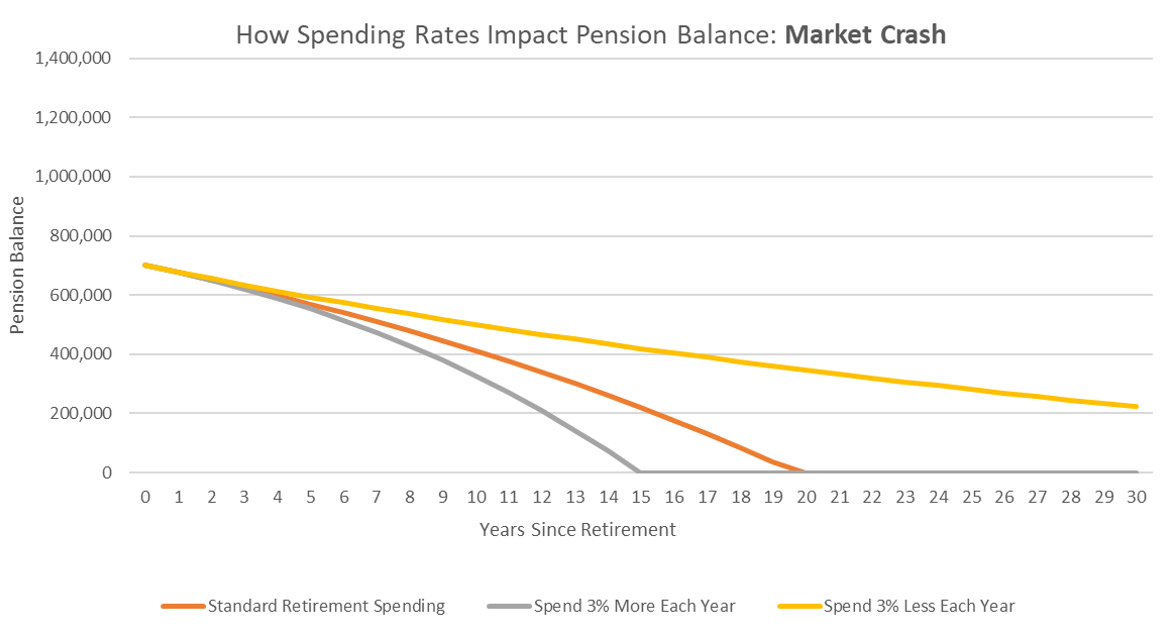

Additionally, this drop off in spending can help soften the impact of a market crash shortly before retirement (Figure 2). If we consider a 30% drop in asset values, but still take the same annual withdrawal amounts as before, decreasing spending throughout retirement mitigates longevity risk and helps reduce the chances of funds running out.

Figure 2: How spending rates impact pension balance in a market crash scenario

Experience navigating retirement

Financial advisers are well positioned to coach clients that may have recently entered or are considering retirement. Their experiences with other clients who have successfully navigated retirement for many years are real-life examples of the lifestyle changes and reduced spending behaviour that evolves naturally.

In addition, clients of financial advisers will be better placed to amend their short-term behaviour and, combined with changes to minimum withdrawal rates, will be more resilient in the face of ongoing volatility. This may mean dialling back areas of discretionary expenditure in order to focus on the essential costs of daily living.

Incorporation of conservatism within the planning process, whether captured in client goals, the use of bucket strategies or implementation of portfolio risk management approaches can be a boon in times such as these.

Key assumptions and methodology

A 30-year timeline has been used, with an initial withdrawal of $50,000 p.a. A flat withdrawal amount is compared with an amount increasing by 3% annually and one decreasing by 3% annually.

A starting account balance of $1,000,000 has been assumed along with a rate of 4% growth p.a. on this balance, post withdrawal each period.

In the market crash scenario, the starting account balance was decreased to $700,000 to simulate an instantaneous 30% drop in asset values.

Wade Matterson is a Principal, Senior Consultant, and leader of Milliman’s Australian Financial Risk Management practice and a fellow of the Institute of Actuaries of Australia. This article is general advice only as it does not take into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular person.