The holiday season was an ideal time to pause and ponder the big questions about our personal and family wealth:

- How much money do we need to live the lifestyle we want?

- Will we run out of money?

- Should we tighten our belts, or can we afford to spend a bit more?

- Will we have enough to leave the next generation or to help out our family before we go?

- Did our investment returns in 2021 get us closer to our goals?

- Do we need to change strategy or put away more or less?

These are all great conversations to have with your family and with your adviser. Meanwhile, it is also a good time to think more broadly about wealth, and how it shapes the world around us.

Amid a pandemic, the rich did well, others not

2021 was another year when the rich got richer, without even getting out of bed. The value of our shares and real estate rose magically without us having to do anything at all. Covid stimulus policies accelerated the post-1980 trend toward inequality of wealth and incomes, which are now at extreme levels of inequality not seen since the 1920s.

2021 also saw the creation of record numbers of wealthy people (‘billionaires’, ‘millionaires’, or any other definition) in Australia and in every other country, although 100 million people were sent back into extreme poverty (World Inequality Report 2022). Inequality rose in terms of access to vaccines, not just in wealth and incomes.

The winners of 2021 were the owners of shares, real estate, businesses, especially those with gearing on cheap debt. For the working, the winners were the ‘knowledge workers’ who can work from home or anywhere. The losers were the physical workers who can't ‘work from home’ in the lockdowns, and border closures, and disruptions.

Also among the losers are people relying on bank interest, fixed incomes, bonds (although indexed bonds and pensions did get a rise at last with inflation finally arriving) They are the savers, renters, and ordinary workers of the world, with rising prices of food, petrol, utilities, rents, and falling real wages.

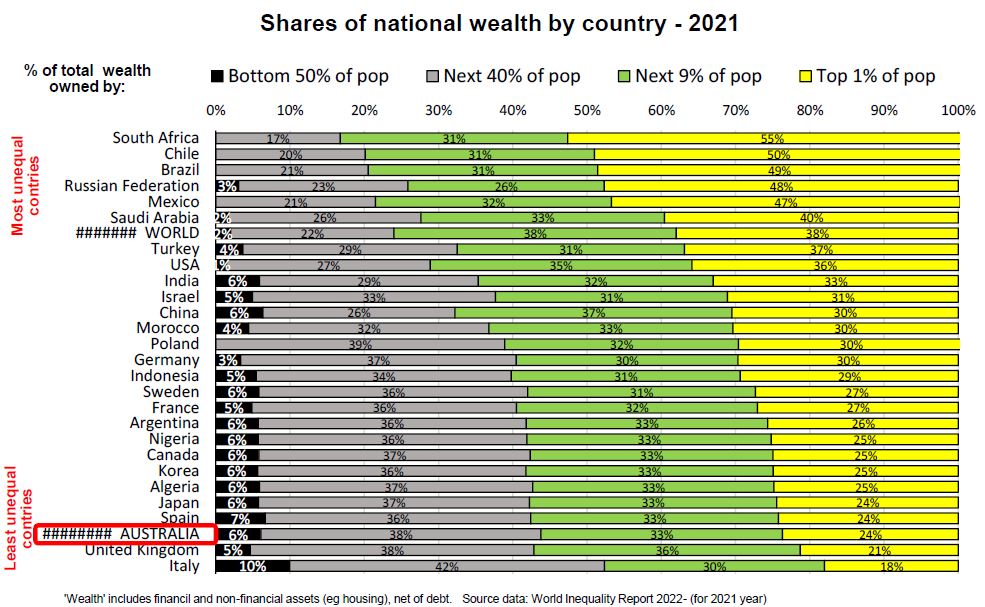

This chart shows the proportion of total national wealth owned by the wealthiest 1% down to the poorest 50%.

A world of growing inequality

Half of the world's population (3 billion adults) between them own less than 2% of the world's wealth (black bars in the chart above), while the richest 10% own 76% of it. The richest 1% (gold bars in the chart) owns 38%, the richest 0.1% owns 19%.

Before we go any further, we need to remind ourselves that we are in the richest 1% that own 38% of the entire world's wealth. The entry-level to get into the world's richest 1% is just US$1.1 million (A$1.5 million) in net assets, including the family home. We have been conditioned to believe that A$1.5 million in net assets (including the family home) is nowhere near enough to fund a ‘comfortable’ lifestyle, but 99% of the world's population has less than this. 50% of the world's population owns assets worth less than US$4,000 each.

Australia among the 'least unequal'

The above chart is sorted from most unequal distribution at the top to least unequal at the bottom. Australia (along with the UK and Western Europe) is one of the least unequal countries near the bottom of the table thanks to our long history of relatively high wages, broad welfare systems and, more recently, compulsory ‘super’.

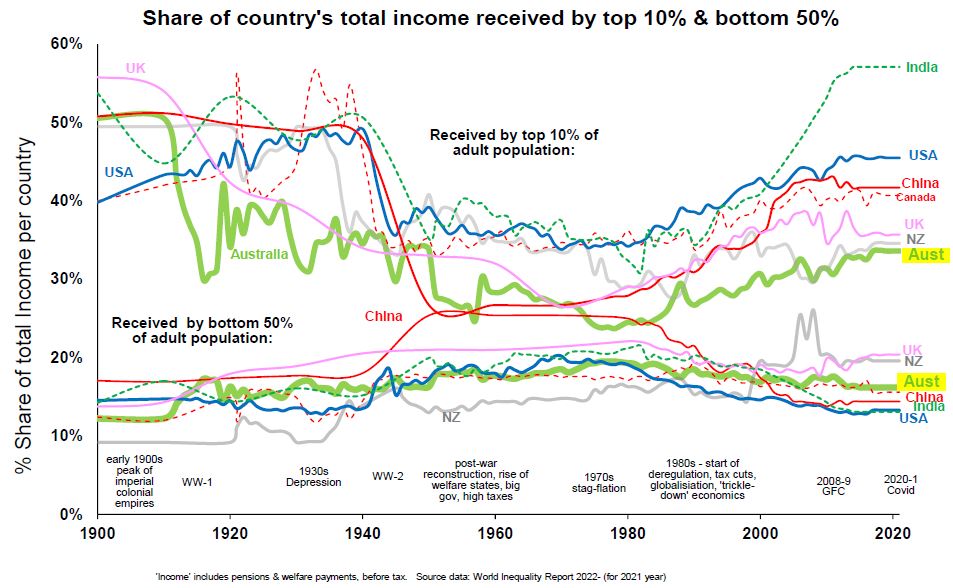

The next chart shows the trends in inequality since 1900 in terms of the share of national income received by the top 10% (upper section) and by the bottom 50% (lower section) for selected countries.

Here we also see that Australia has been among the least unequal – i.e., relatively low share of total income going to the top 10%, and relatively high share going to the bottom 50% of adults. Inequality peaked in the roaring 1920s, then reduced dramatically in the 1930s depression, WW2 and in the post-war boom, but has been rising steadily in the post-1980 era of tax cuts, deregulation, globalisation of trade, outsourcing of jobs to low-wage countries etc.

Social and political reactions to post-1980s inequality accelerated in the GFC, when government bail-outs of banks and bankers’ bonuses gave rise to movements like ‘Main Street not Wall Street’, ‘Occupy Wall Street’ and the’ 99 percenters’ in the US and across Europe. It was coupled with high unemployment and xenophobia. Rising inequality has fuelled the dramatic rise of populist, nationalist, anti-globalisation movements across the world.

Why rising inequality matters for everyone

Why is rising inequality important for investors? From a personal perspective, it is natural for the rich to say, ‘I've earned it, so I deserve it, and I'm hanging on to it!’ Rising inequality is important because it fuels social divisions and unrest across the world, and social unrest can spark events that disrupt investment markets, sometimes resulting in the widespread destruction of wealth.

There are two main schools of thought on how rising inequality plays out.

On the one hand, we have the optimists like Simon Kuznets and Robert Solow (as well as Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say) who believed that inequality will automatically self-correct so that the benefits of growth are shared around to all (cue the magic fairy dust here!).

On the other hand, we have the pessimists like Thomas Robert Malthus, David Ricardo and Karl Marx, who believed that rising inequality does not magically self-correct but it rises in a self-perpetuating spiral to a point where social unrest flares up in the form of revolution or regime change, to bring about a ‘fairer’ distribution of the spoils.

At a personal level, we can each make plans about how we distribute our wealth, including via charitable foundations or sub-accounts (with financial advice).

From a portfolio perspective, social and political disruptions are medium-term risks that should be tracked to assess possible impacts on financial markets. Our base case is for slow economic growth and rising wage pressures (ageing populations, fewer workers) fuelling further inequality, social and political disruptions, made more volatile by interest rates rising to fight inflation, and budget pressures to raise taxes and cut government spending.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.