Short selling (or ’shorting’) literally involves selling something you don’t own. Here’s a hypothetical example of the basic steps involved:

- An American hedge fund manager thinks the price of ANZ shares is going down.

- The hedge fund doesn’t actually own any ANZ shares so it borrows the shares from an Australian fund, and then sells the borrowed stock on the market.

- At some point the hedge fund will need to buy back the shares and return them to the lender.

The profitability dynamics of those steps are reasonably straightforward. Let’s assume the hedge fund borrowed ANZ shares at $30. Ignoring the small amount of borrowing and transaction costs involved in establishing the short position (usually less than 1.0% p.a.), the hedge fund will profit if the price of ANZ falls below $30. However, if the price rises above $30, its short position will incur a loss when the shares are bought back.

Hedge fund activities raise the ire of some market participants who see them as unscrupulous predators exploiting the very market instability they helped create. There’s no doubt that short selling can exacerbate a market panic – sometimes leading to a ban on the practice (the most recent example being in China).

We believe that the ability to short sell is fine in a normally-functioning market, as it actually adds to the liquidity and efficiency of a market.

Short selling is not without risks, as share prices can go up as well as down. Shorting Australian banks has indeed been a losing trade for a long time (referred to as a ‘widow maker’ in market lingo), but this hasn’t stopped hedge funds from continuing with the practice.

Why Aussie banks are perceived to be the next ‘Big Short’

The Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) discloses the amount of a company’s shares that is shorted. For our major banks, the number is currently around $7 billion, close to a record high. Although it’s certainly a big number, it represents only 2% of the total value of the banks. This compares to Myer, for example, which has around 11% of its market value shorted!

Given the dearth of hedge fund managers in Australia who can short-sell, it’s reasonable to assume that most of this activity originates offshore. The term ‘Big Short’ is the title of a book (and now made into a movie) written by Michael Lewis which (simply and colourfully) documented the GFC through the eyes of four very successful hedge fund managers.

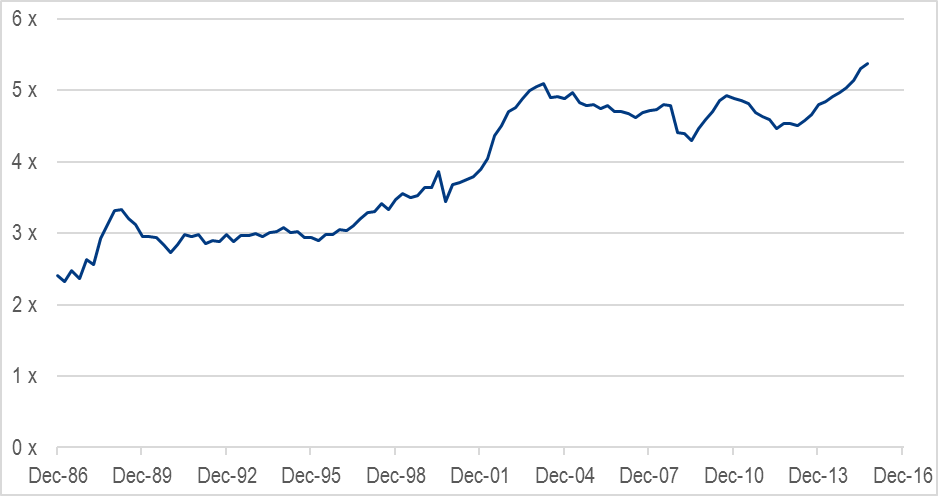

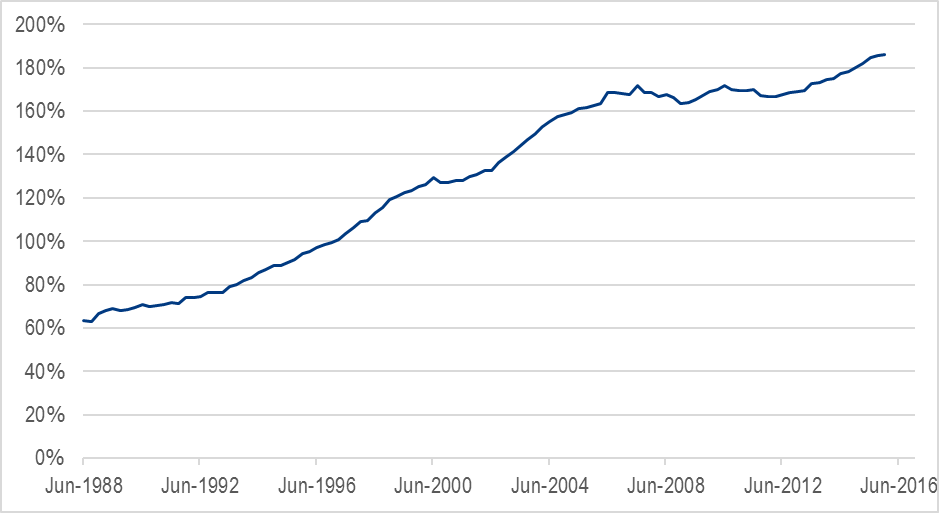

The following two graphs capture the essence of the short selling argument. Graph 1 shows asset prices growing at a rate far in excess of income growth. This has been made possible by increased borrowings as shown in graph 2.

Graph 1: House price to income ratio

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Graph 2: Household debt to income

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

History tells us that extreme valuations fuelled by high debt is an accident waiting to happen. In the most pessimistic commentators’ eyes, the Australian situation resembles the bubble we witnessed in America and Ireland leading up to the GFC – and we know how that ended. Given that around 50-70% of Australian bank loans are secured by housing, the implications of a housing crash are self-evident.

Other features of the Australian environment also bear an unfortunate resemblance to the American experience. In particular, there’s mounting evidence of an apartment oversupply projected to continue for the next couple of years as developers complete the current construction pipeline. Sharp falls in prices (up to 30%) are now being recorded on some apartments bought off-the-plan at the height of the boom and some developers and investors will lose money.

The major banks claim they have limited exposure to high-risk property developers, although there’s little doubt that they have played their part in fuelling the boom. In 2014, around 40% of all housing loans written were interest-only investment loans (as distinct from loans to people who are buying a primary residence). According to our analysis, we believe at the peak, some banks were writing over 50% of new business in interest-only investment loans.

Fortunately, the banking regulator, APRA, clamped down on such practices in mid-2015, limiting investment loan growth to 10%. While it’s comforting to see bank lending on a more prudent path, it is somewhat of an indictment of bank management that it has required the ‘big stick’ of the regulator to make it happen.

Not all bubbles burst; some just deflate

Forecasts of a crash in Australian house prices are not new, and of course the property market didn’t come through the GFC unscathed. Property prices will always remain vulnerable to large systemic shocks, principally recessions. However, a general collapse in housing prices leading to a sharp rise in bad loans and write-offs for the banks is far from inevitable, given some mitigating factors.

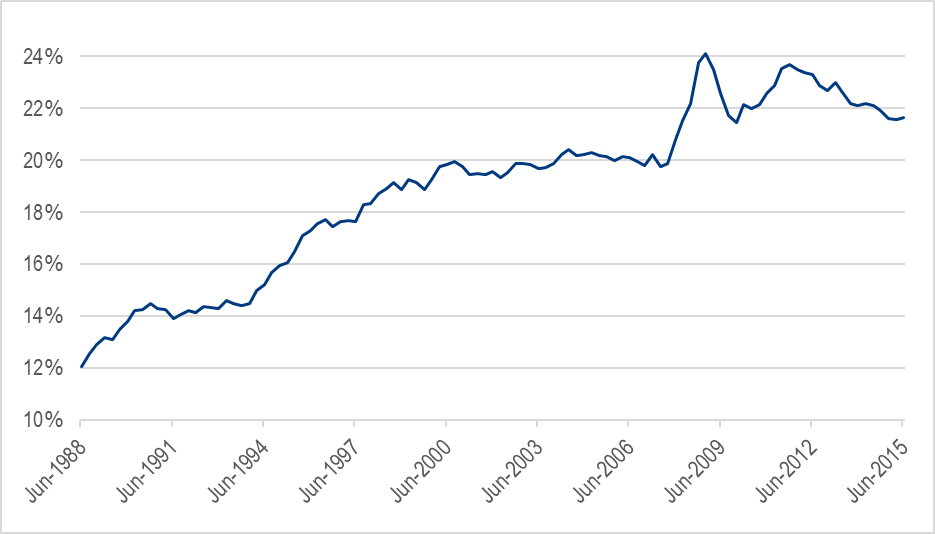

Compared with the commonly referenced data in the first two graphs, graphs 3 and 4 paint a very different picture of the state of household finances. Unlike graph 2 which compares the amount of debt to annual income, graph 3 compares debt to total assets.

Graph 3: Household debt as a percentage of assets

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Based on this data, Australian households – on average – currently look far from a debt crisis, with the value of assets about four and-a-half times greater than the value of debt.

Clearly, there are individuals above and below the average. However, we gain some comfort from the stricter lending criteria in recent years, which should help limit borrowers from over-extending.

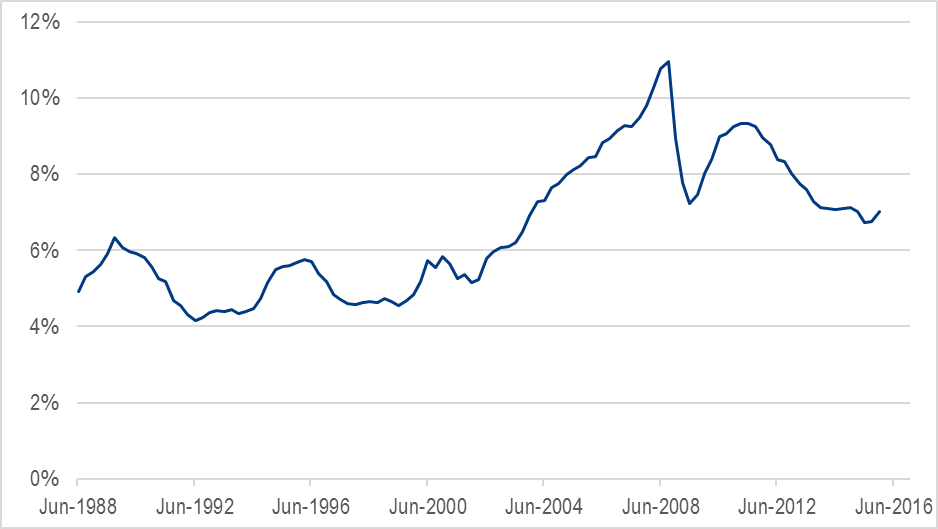

To complete the picture, we also need to look at debt serviceability. That is, how onerous is it for Australian households to meet their interest payments? Graph 4 shows that on average, at current interest rates, only 7% of income is required to meet interest bills. On this measure, household affordability is nearly as cheap as it’s ever been.

Graph 4: Debt servicing (housing interest payments to income)

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

Nevertheless, assets can go down in price whereas outstanding debt only falls with actual repayments so Graph 2 is not totally irrelevant. It is arguably useful in estimating the potential extent of a debt crisis rather than drawing firm conclusions on the probability of it occurring.

In summary, the pessimists will point to statistics which on face value look alarming, but are also potentially misleading. The reality is that ‘on average’ Australian households have assets well in excess of debt and even if asset prices fall, the ease with which the debt can currently be serviced provides a cushion if income is maintained.

And this is the crucial point – it’s all about employment. If Australia can maintain unemployment around current levels, there’s no reason why the bubble has to burst. It can simply deflate, with a gradual decline in house prices and gradually rising incomes.

Fuelling the fire are bad corporate loans

With our major bank shares currently trading around 30% below the highs of March 2015, the short sellers appear to have the upper hand, despite the absence of a housing crash. How so?

The latest swoon in the share prices followed ANZ’s announcement that impairments (i.e. expected losses) on their corporate loan book would be “at least $100 million higher” than previously guided. Recent failures such as Dick Smith, Slater & Gordon, Arrium and Peabody Resources are well known to the market so an increase in impairments (particularly from a historically low level) should not come as a surprise. However, in the week following the announcement $8 billion was wiped off ANZ’s market value!

The market’s reaction reflects concerns that ANZ's announcement is the tip of the iceberg, and talk of dividends being slashed to shore up capital is gaining traction. While a cut in dividends is possible, it is premature to predict they will be ‘slashed’. And by no means are all of the banks equal.

During the GFC the major banks cut their dividends on average by 20%. However, to put this in context, at that time CBA’s ratio of bad debt costs to total loans was around 4.5 times higher than the level reported in its latest financial results.

At this point, with bank shares well off their highs, it seems that the bank short sellers are right, but for the wrong reasons.

John Pearce is Chief Investment Officer at Unisuper. This information is of a general nature only and has been prepared without taking into account any individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making any decision in relation to your personal circumstances, you should consider whether to consult a licensed financial adviser.