Much is being written about what a post-super-reform world will look like. The impact in that world on the popular estate planning strategy, the withdrawal and re-contribution, has not been given much attention.

Here’s how it works

Assume I am 63-years-old and retired, with $2.5 million in super. Let’s say, in homage to one of the greatest acts of tax generosity in Australian history, $1 million is tax-free courtesy of a $1 million non-concessional contribution I made just before 30 June 2007.

If I die tomorrow and my entire superannuation balance is paid to my adult children, then they will have to pay $255,000 in tax ($1.5 million x 17%). The taxable component is subject to a non-dependant death benefit tax while the tax-free component is exempt from tax. Non-concessional contributions form part of the tax-free component.

A popular estate planning strategy is to withdraw $540,000 from my super fund which is tax-free as I am over 60 years of age. I could take this as a lump sum or as a part-pension which would not be subject to a maximum payment amount because I am over my preservation age and retired. Were I not retired, any withdrawals would probably be subject to a maximum 10% under the transition-to-retirement pension rules.

I then recontribute that $540,000 as a non-concessional contribution. I am allowed to do this because I am under 65-years-old so the three-year bring forward rule for non-concessional contributions is available. I am not subject to a work test, because I am under 65 years old. Maybe I will wait a month to undertake the re-contribution. Maybe I will do it in a couple of weeks. According to private ruling 1012443439489, the timing doesn’t really matter and I won’t offend the general anti-avoidance provisions contained in Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936. The conclusion in that ruling (bearing in mind that private rulings are only binding on the Commissioner to the extent that they apply to the specific rules in relation to those specific facts), is that because any payment from my super fund is tax-free in any case, the re-contribution strategy will not provide me with any tax benefit and my financial position, therefore, will not change and there is no tax benefit. So why bother?

After the re-contribution, the tax-free amount of my $2,500,000 superannuation balance becomes $1,540,000. The taxable component of my balance becomes $960,000. Upon my death, if my entire balance is paid to my adult children, they will have to pay tax of $163,000.

With a few clicks of the mouse, I will have saved my kids $91,800. Better than bank interest, as they say.

Why is it (probably) over?

Simply put: because I already have $1.6 million in super. Schedule 3 to the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 introduced the requirement that an individual must have a total superannuation balance of less than (currently) $1.6 million on 30 June of the previous financial year to be eligible to make non-concessional contributions.

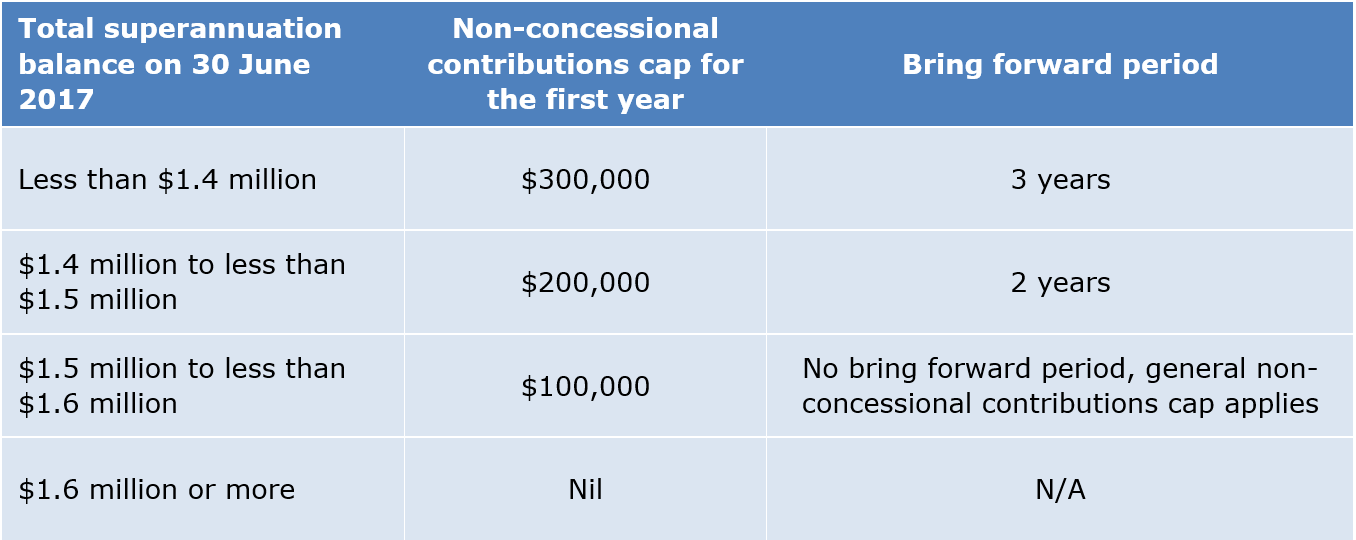

Actually, saying “it’s over” is probably a bit extreme. However, it’s going to be available only to those with superannuation balances under $1.6 million. And it will only be available, to any significant degree, to those with balances under $1.4m due to the limits to be placed on the use of the three-year bring forward rule (which will now, of course, only allow $300,000 rather than $540,000) as summarised in the following table as it will apply in the 2017-2018 income year.

What can we do in the lead up to 30 June 2017?

Not much really. It is what it is. Anyone in the position to undertake a re-contribution strategy might consider doing so because the opportunities to, and advantages of, doing it after 30 June 2017 are going to decrease. Even those who cannot take advantage of the three-year bring forward rule (that is, they are over 65 but still “gainfully employed”) could potentially save their adult kids $30,600 by doing a withdrawal and re-contribution of the current one-year maximum of $180,000.

It’s still better than bank interest and, who knows, depending on when you die that might even cover a year’s worth of private school fees for one of your grandkids in Sydney.

Stephen Lawrence is a Lecturer, Taxation and Business Law School, UNSW, Chartered Accountant and Member of the International Tax Planning Association. These views are considered an accurate interpretation of regulations at the time of writing but are not made in the context of any investor’s personal circumstances.