Bank shareholders have benefited tremendously from 25 years of cartel monopoly pricing, gobbling up of small competitors, lax controls, sleepy regulators and the absence of an economic recession.

The Royal Commission has uncovered institutionalised greed, fraud, fee gouging, mis-selling of inappropriate products, predatory lending, document forging, market rigging, lying to regulators and a host of other regular dishonest bank practices. These actions were conscious decisions which lined the pockets of bank staff at every level from the boards of directors down to branch tellers. They have also showered shareholders with windfall profits and dividends.

The current CEOs say they are embarrassed by their banks' failings and while apologising for past mistakes, remediation costs will run into billions.

The financial sector is a notoriously high-paying industry relative to its contribution to society. It is not just the sales commissions and bonuses paid to staff, but the base salaries and benefits are much higher than most other industries. Out of the $20 billion paid to 160,000 bank staff last year, probably 20-30% of it - or around $4-6 billion each year - was a windfall gain that would not be there if the industry was competitive, efficient and honest. Likewise, probably a similar proportion of the combined $25 billion in dividends paid to bank shareholders last year was also a windfall gain.

Will the government break up the big banks as Roosevelt did with US banks in the 1930s? Unlikely, but it depends very much who is in power in Canberra. Remind me – who is in government this week?

Recessionary impacts on banks

The last recession in Australia was in the early 1990s, which ended the bank lending binges of the 1980s. The worst of the major lenders were Westpac and ANZ, but even worse offenders were the state banks of every state government except Queensland (which no longer had a state bank). The property collapse and Paul Keating’s ‘recession we had to have’ exposed enormous piles of bad debts that nearly destroyed Westpac and ANZ. It resulted in the closure and breaking up of every state-owned bank in Australia. The ‘good’ loans were given mainly to CBA, and the bad debts were borne by taxpayers in each state.

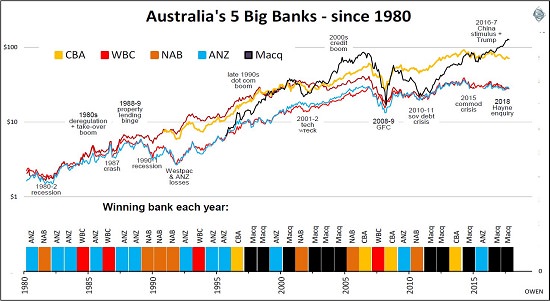

The chart shows share prices of the big five banks since 1980, with the winning bank each year shown at the bottom.

Click to enlarge

Recent history and how easily we forget

Westpac and ANZ are in virtual lockstep during this period although they had different histories. Westpac was formed in 1817 as the Bank of New South Wales, Australia’s first locally-owned bank and the first locally incorporated company. It survived several near-death crises in its first few decades but emerged as Australia’s largest bank for most of the time since.

Melbourne was financed mainly by British investors via British banks. The current ANZ is the result of a merger of three ‘Anglo’ banks in Melbourne. For most of its life, it was the weakest of the big banks, with more aggressive lending and lower capital levels.

After the banking industry was deregulated in the mid-1980s, Westpac and ANZ joined in the mad lending boom being led by the state-owned banks. Prior to the 1987 crash, most of the bad lending was to ‘entrepreneurs’ like Alan Bond, George Herscue, Chris Skase, Robert Holmes a’Court, Russell Goward, John Spalvins, John Elliott and many others – to finance their crazy take-over deals. The 1987 crash ended the takeover boom (and the ‘entrepreneurs’ were bankrupted, jailed or ran off to hide in Spain), so the banks turned their attention to bad lending on property.

To quell the boom the RBA hiked interest rates to 18% at the end of 1989, sending property prices down and many thousands of borrowers bankrupt. Westpac lost $2 billion in 1992 and was raided by Kerry Packer then rescued by Lend Lease (which owned MLC), while ANZ lost nearly $1 billion. These numbers are the equivalent of tens of billions of dollars in today’s terms. In 1992, Westpac had only $6.7 billion of equity supporting $110 billion of assets, so the bad debt write-offs of $5 billion in 1992-1994 almost wiped out its equity. Today’s equivalent would be a $50 billion loss that would wipe out almost all of Westpac’s $60 billion in shareholders’ funds. (If that happened today the regulator would probably close the bank, write off all hybrids and subordinated debt to zero and force the bank to raise new capital at a fraction of the prevailing share price.)

From the start of 1990 to November 1992, Westpac and ANZ shares fell 55% but NAB fell only 5%. NAB under Nobby Clark refused to join in the orgy of bad lending. NAB suffered minor bad debt write-offs and it suddenly went from being the smallest of the big banks to the largest. The chart shows how the share prices of NAB and the newly-listed CBA sailed higher for the next 20 years while Westpac and ANZ licked their wounds.

Overseas adventures and vertical expansions

Unfortunately, the banks went mad on a string of failed overseas adventures. NAB completely squandered its lead and is now the smallest of the Big Four again. It thought it could teach the British how to do British banking and it thought it could teach the Americans how to do mortgage lending. Westpac also bought banks in the US. ANZ acquired a network of banks in Asia and Africa in an attempt to ‘get big’ to compete with Westpac and NAB. It shed them in the 1990s because it didn’t know what to do with them. Then it spent the 2000s getting back into Asia under Mike Smith, but is now retreating back to Australia under Shayne Elliott. Oh dear.

These overseas adventures by NAB, Westpac and ANZ wasted billions of dollars of shareholders’ money, but they provided bank directors and executives with endless prestige, free travel and entertainment.

After failing dismally overseas, the big banks (including CBA this time) turned their attention to buying up insurance companies, fund managers, financial planning groups and mortgage brokers at home, so they could ‘cross-sell’ conflicted internal products to their unsuspecting bank customers.

One change that has been significant over the whole period is the type of business done by the banks. Westpac, NAB and ANZ (and their predecessors) all started out as commercial banks, primarily for short-term lending to business. That’s what banks do – short-term cash flow loans to business, funded by short-term deposits. Long-term lending to business is done by institutions with long-term liabilities such as life offices. Mortgage and personal lending was done mainly by building societies and credit unions.

The banks have now become primarily home mortgage lenders. Building societies turned themselves into banks and most were bought up by larger banks. Today, the big banks are essentially giant building societies, but with ludicrously overpaid executives.

The 1890s banking crisis was caused by bad lending to residential property developers, the mid-1970s crisis was mainly bad lending to commercial and residential developers, the mid-1980s crisis was bad lending to corporate takeover deals, and the early 1990s crisis was mainly bad lending to commercial property developers. The next banking crisis will be caused by an unwinding of the current boom in housing lending which is financed by the big banks.

Whatever asset is inflated by bank lending deflates when the boom ends.

Macquarie - the fifth one

Macquarie is different. It has a banking licence but it's mainly an asset manager and deal-based investment bank. It has been run by a succession of wily operators. It has always been an innovator that developed new markets for itself rather than competing head-on with the banks. It is one of the few home-grown Australian businesses that have succeeded globally. It nearly blew itself up in the GFC with its fancy structured products and paper-shuffling deals. It narrowly survived and cunningly used the taxpayer-backed government guarantee to buy up cheap operations overseas.

In the chart above, Macquarie won in five out of the past seven years, and 11 out of the past 21. It should remain ahead while the Big Four deal with the Hayne fallout.

[Disclosure: I bought shares in ANZ and Westpac in the 1990s crisis and Macquarie in the early 2000s but have not bought bank shares since then (aside from taking up emergency discounted rights issues in the GFC). I still retain the early shares.]

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.