The last few years have provided an enthralling comparison in the many facets of life between Australia and the USA. From a pandemic perspective, the Australian mortality statistics speak for themselves in our appropriate handling versus the fractured attempts by our strategic allies.

Australia's sensitivity to interest rates

From an economic standpoint, however, the resumption of 'normal' monetary policy may be an area where 'the land of the free' has a structural advantage to emerge victorious.

One of the many issues that confront central bankers worldwide is that in the face of surging inflation, low unemployment, and the strength of their currency (for those that care), they have at their disposal one lever to exert force on their respective economies.

Raising rates to help cool the economy makes sense. It increases the cost of borrowed capital for all and sundry, quelling frothy asset speculation both at a household and industry level. It can help to dampen government spending and is helpful to cast a pallor over excitable and speculative projects that need reconsidered using a rising risk-free return.

What's more, when viewed at a distance, this primary mechanism offers simplistic answers to the economic problems of the day. It is hard not to like it.

As past Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), Glenn Stevens remarked in 2008, the cash rate has been described as a 'blunt instrument' to exert influence over the economy.

So does it have the resolution to steer the next century's fast-moving and highly levered economies? Well, that can depend on how these economies are geared.

Similar and yet so very different

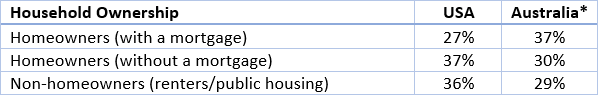

Australia and the US (like most developed countries) share similar traits concerning homeownership, as shown below:

Sources: policyadvice.net and abs.gov.au. *Data provided does not equal 100%.

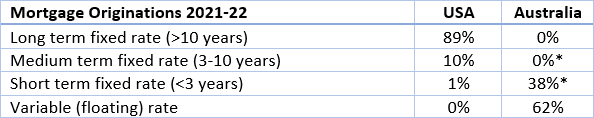

Where the similarities end, however, is with the predominance of the US fixed long-term (usually 30, sometimes 15 years) home loan versus Australia's obsession with either short-term fixed or variable rate mortgages:

Sources: bankrate.com and abs.gov.au. *Data provided does not indicate fixed rate term length, however 2 years is predominant.

The US is the only country in the world in which the 30-year fixed rate residential mortgage is the dominant home mortgage product. The ability for Americans to easily access relatively cheap long-term money at a fixed rate serves several purposes.

From a borrower's standpoint, a fixed rate mortgage (FRM) allows a reliable and standard repayment, fixed for the considerable life of the loan. This may account for the higher percentage of 'free and clear' owners in America over Australia, as it could well be the only mortgage they ever need. A notable feature is if the borrowers situation changes after a few years and the home needs to be sold, there is no prepayment penalty for closing the loan.

From a lender's standpoint, the situation is a little less rosy. Just the thought of locking in a market acceptable rate for 30 years would be enough to give an Australian banker heartburn. Enter government intervention. The one critical defining difference is the ability of banks to shift this risk onto a willing buyer, in this case, the US government-backed Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac). With the interest risk removed, these products suddenly become commercially viable to the distributing banking sector.

In Australia, it's a different story. For those banks willing to offer 'extended' fixed terms, usually only up to 10 years, the internal interest risk mitigation usually means unenticing rates to the market. On top of that, borrowers are faced with severe penalties if they need to move house and 'break' the term if interest rates have fallen. Without the backstop of a federally-supported entity to remove this risk, it isn't easy to see the extended fixed-rate market maturing properly here.

So, what would motivate the Australian government to bother with such an initiative?

Structuring for a sharper instrument

The quantum of the impact that central bank rate rises have on the general population can differ materially depending on the predominant mortgage structure.

As we see today, central banks globally have moved to restore cash rates from their pandemic lows, with notable and often significant upward movements. Leaving aside the great lifts on a percentage basis owing to the low base effect, these changes are flowing rapidly and by design to households with mortgages.

In the US, this means a real impact on new mortgages at the margins but leaves the remaining loan book largely unharmed. A benefit of this outcome is especially relevant when you consider the younger loans where recent first home buyers are borrowers are often the primary risk case for severe property price downturns.

In Australia, due to the prevalence of variable loans, be it first home buyers or not, the effect of rising rates is felt immediately by most with a mortgage. The ability for the RBA to create ‘mortgage stress’ comes at a much lower level when compared to the US, especially given the enormous growth in personal debt levels over the last two decades.

Their unique mortgage structure allows the US Federal Reserve a lot more 'headroom' for raising rates to meaningful levels when looking to address the many other components of their financial system. By reducing the direct impact on the real estate coalface, there is now an opportunity to hone cash rate pressure to areas such as commercial and government demand without the risk of destabilising the whole economy in the process.

In Australia, however, the omnipresent risk of suffocating demand on a household level while trying to reach meaningful cash rate levels for other areas of the economy is genuine. If the RBA wants a sharper stick, it may need to consider funding an Australian ‘Fannie Mae’ (feel free to offer another name in the comments).

The future indicates that increasing debt loads are almost a certainty, and it brings the need for a reflection on whether the present structure in Australia offers the best fit for the main instrument available to our central bank. As we emerge from a decade of expansionary monetary policy into a tightening one, the time is nigh to consider extended fixed-rate mortgage alternatives.

Tim Fuller is Head of Wealth at Strata Guardian. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.