Basic economics taught at school and revisited in first year economics at university, is overlooked when explaining the failure of Australia’s housing market to work effectively for Australians.

The current difficulties confronting both monetary and housing policy partially stem from the explosion of mortgage debt. Therefore, what follows is my view on one of the least discussed but fundamental causes of the housing price bubble in Australia - and it flows from an understanding the basics of market price theory.

Supply and demand obviously dictate the price of housing, but housing policy aimed at addressing affordability, needs to consider the perverse impact of debt. In particular, the availability and the cost of debt (mortgages) has fuelled a house price bubble.

Low interest rates, low deposit requirements and therefore the provision of excessive levels of mortgage debt have, over time, added to driving housing prices higher. Today, Australia has the most expensive houses in the world when measured against income. House prices have become unaffordable for many – particularly young families.

I am not suggesting that debt and its cost is the sole cause of our great housing price bubble, but there is a lack of acknowledgement of their role. The lack of regulatory intervention in the mortgage market exposes the failures of the RBA, APRA, and Treasury. Indeed, have any of these bodies acknowledged that our housing price bubble poses a serious risk to long term financial stability, social cohesion and if unchecked condemns future generations to a declining standard of living?

Whilst the liberalisation and deregulation financial markets was a necessary policy initiative 40 years ago, it has surely contributed to Australia’s housing price bubble of today.

My view is that deregulation of financial markets has been excessively unconstrained. A thoughtful appraisal, during the last 40 years, of the consequences of financial deregulation has not been undertaken. There has not been a review or analysis to identify the point at which deregulation went from supporting wealth distribution to causing wealth dislocation. At what point did it cause a greater divide in the distribution of wealth by fuelling asset price inflation? Further, has there been adequate analysis of the flow-on effect of quantitative easing (QE), the driving down of interest rates (negative real rates) and the creation of excessive debt in Australia’s mortgage market?

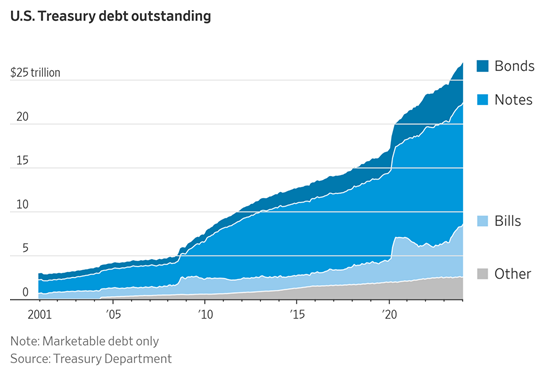

An interesting corollary is the analysis of the government debt explosion across the developed world. It is observable that low interest rates and QE, have been used to fund governments that have failed to address the demographic challenge (aging populations) that was well predicted at the turn of the century. This is clearly on display in the United States where a government debt explosion has accelerated since Covid.

Ageing populations with low birth rates have combined to cruel government budgets that have tried to sustain basic social needs but are now confronted by poor wealth distribution. QE has been used as a ‘go-to default mechanism’ to drive down bond yields so that governments could run deficits and increase debt without suffering higher interest payments. The likelihood is that it will need to be reintroduced because governments cannot balance their budgets.

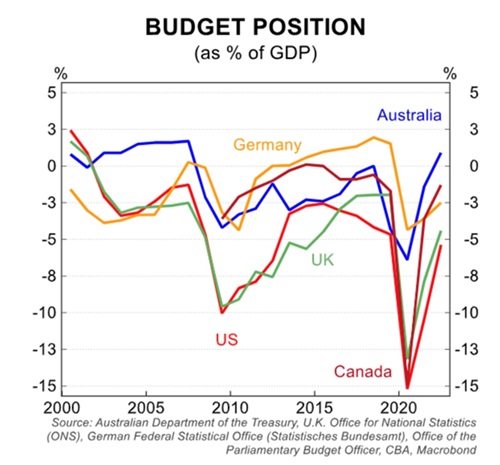

In Australia, we do not have a government debt problem (ex Victoria) and have a strong budget position (as shown above). However, we have a large amount of household debt (100% of GDP) concentrated with just a third of homeowners. Those households that have bought in the last 5 years have large debt balances and they need sustained lower interest rates to service their debt – just like many developed world governments.

Basic market theory explains how debt pushes prices

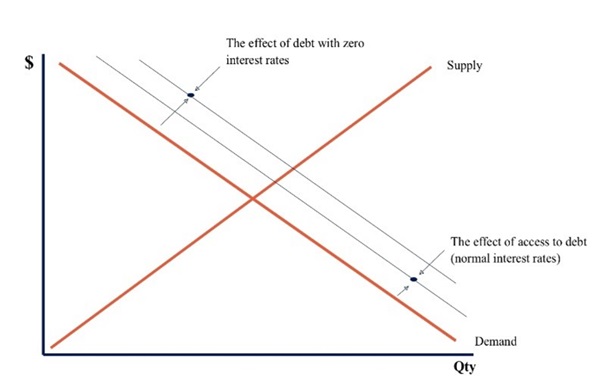

Below I have produced two simple tables to explain how the creation of debt (leverage) pushes the price higher in clearing the housing market. From that, I will show as to how low interest rates compound the effect of leverage.

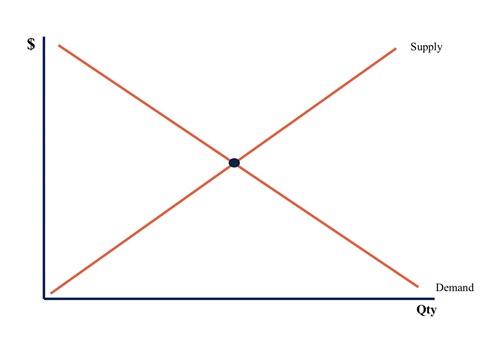

The theoretical market clearing price, where purchasers of a house have no access to debt, is shown in the simple table below. The price that buyers are willing or can pay is limited to their savings or capital. A supplier or seller of a house merely decides or agrees to sell at the price bid. The graph logically predicts that a house builder will surely supply more houses if the price rises because their development or profit margin will increase. Market theory at its simplest.

The chart below shows the effect on market clearing prices when debt is accessible to the buyer. The first push higher is the effect of normal debt (added to the savings) with normal interest rate settings – i.e. debt set at a margin above inflation. The second push higher may be described as the effect of low-cost debt. More debt can be accessed (borrowed) if the cost of servicing that debt is low. A buyer can afford to pay more for a house. This particularly describes what occurred in Australia at the end of Covid when our cash rates were cut to 0.1% and remember the RBA predicted that they would hold them there till 2024.

Market theory therefore reflects reality by predicting that the market price for housing is set by a willing buyer who can pay more by accessing debt. A willing seller will benefit from a market price inflated by debt.

Theory to observation

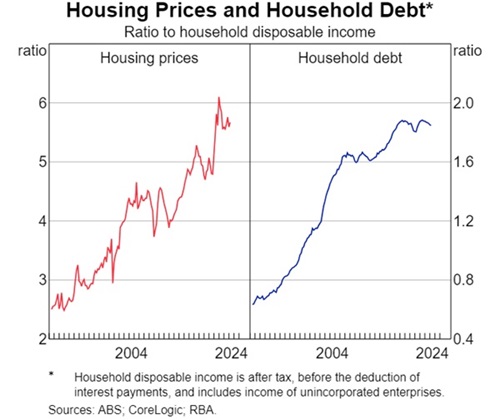

The chart below shows the correlation between housing prices and household debt. The more that mortgage debt can be accessed, the higher the ratio of house prices to disposable income.

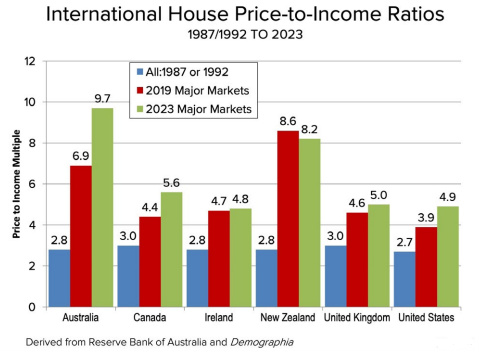

This leads to the observation (noted earlier) that Australia’s housing prices are the highest (and least affordable) amongst our international peers.

The surge in the price to income ratio illustrates the effect of relatively low interest rates. The decline in the ratio seen in New Zealand is explained by the adoption of higher interest rates and the onset of a recession. Elsewhere, there is a broad observation of rising ratios over the last 30 years that suggests that asset inflation has occurred with easy financial conditions and liquidity creation adopted by world central banks.

My conclusion from the above analysis is that both the access to and cost of mortgage debt has been poorly regulated in Australia and therefore contributed to our housing price bubble. The notion that Australian house prices will continue to rise exponentially will be contested by affordability. We have engineered a price for housing (through a debt explosion) that will cause social dislocation and a severe problem for future generations – if it is not addressed.

Whilst banks and other financial intermediaries have facilitated the rise in house prices in the past, there will be a point where they will constrain the availability of debt when they perceive that the ability of borrowers to service that debt has been reached. That point has been manipulated by the low-interest rate settings. However, a reliance on the market to ultimately and independently constrain the rise of house prices has clearly failed as a social policy.

The future may look like this

Australia will at some point undergo a painful reset of housing prices. However, it will be far better to be a managed process through intervention than a reset caused by a sudden unexpected economic event.

What this requires is an initial admission by the regulators and bureaucrats that they have mismanaged mortgage debt creation and the cost of that debt in Australia. The intervention will require the government – in a bi-partisan approach – to absorb the mortgages that are at risk of falling into a negative security position. The funding of these loans may be managed through our superannuation system with government guarantees.

From that point a national housing policy needs to be formed that builds supply, sets the level of immigration, sensibly manages the amount of mortgage creation, specifies minimum deposit requirements, and appropriately resets the excessive taxation benefits provided to leverage in the housing and investment market.

In the meantime, Australia like most of our developed world peers, will need to hold down interest rates. Overseas, it will be necessary to hold down government interest bills. In Australia, it will need to be targeted to keep many housing borrowers from falling behind on repayments.

As I stated above, the policy most likely to be utilised will be QE. However, QE has the insidious effect of supporting asset price inflation when it is utilised without proper debt overlays.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.