It is my view that Australia’s rising house prices, which have persistently compounded at a faster rate than either average wages or average household income, are a measure of ‘economic excess’ - not ‘economic success’. The unaffordability of housing is the result of decades of appalling failure in public policy.

Governments, Treasury and the Reserve Bank never dare to measure their economic management success on the creation and maintenance of affordable housing for the majority of average income earning households. Today, none of the entities charged with directing our economy have enunciated a strategy to deliver this important public policy goal for Australia.

Rather, all seem focused on strategies designed to drive household wealth higher through the compounding of residential property prices, with little consideration of the burden it creates for either young households or for future generations.

The problem with runaway prices

Unfortunately, as time transpires, and as wage growth consistently trails below house price appreciation, unaffordability will increase and expand across society. This will result in the creation of an underclass, populated by those that will struggle throughout their life to own a home. This will occur in a society that today boasts one of the highest standards of living in the world.

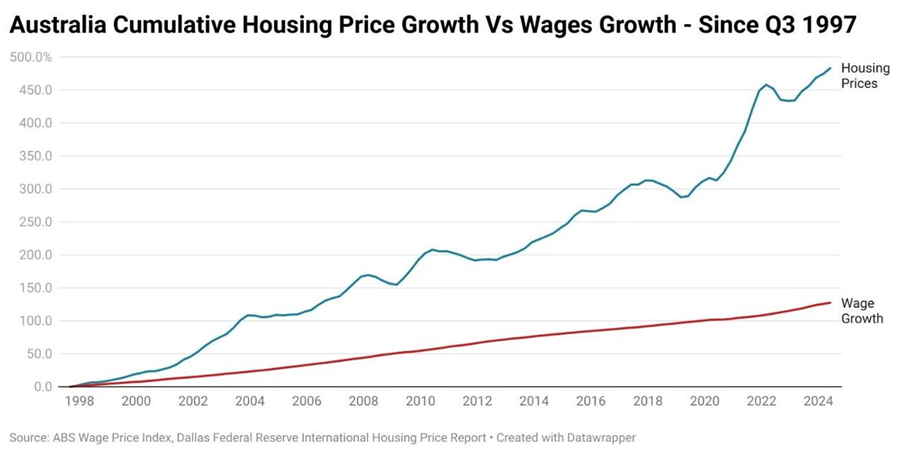

Note: Over the last 27 years, wages have risen by 127.5%, while housing prices have risen by a total of 483%.

The above chart compares the compounded growth in house prices to that of wages. It is a confronting picture that should have concerned successive governments in the periods prior to the GFC, prior to Covid and particularly now in the post Covid period. The 27-year period shows a growing gap between the rise in house prices and wages. It shows why today's Australian house prices have come to trade at historic multiples of household income.

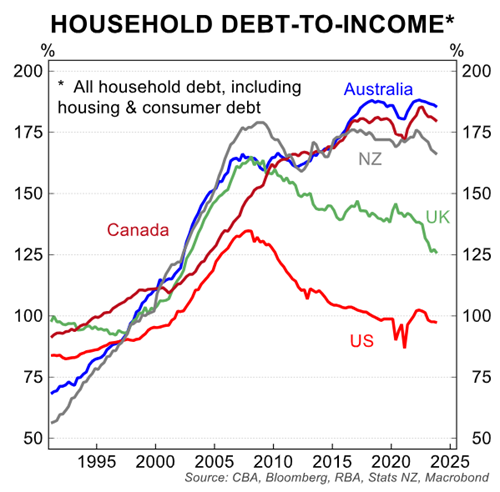

The chart below shows that growth in house prices is substantially correlated to the growth in household debt. Australia now has the world’s highest household debt to income amongst our peers and it has amongst the highest residential property prices.

It is a peculiar measure of ‘economic success’ when the owners of residential property – occupiers and investors – can consistently generate paper wealth through compounding capital gains. The excessiveness of that wealth is measured by the mortgage stress confronting residential property buyers who are driven into debt by their fear of missing out.

Over the last 27 years, Australian house prices have also compounded at a faster rate than consumer prices. Meanwhile, wages have grown faster than the generally accepted measures of consumer price inflation.

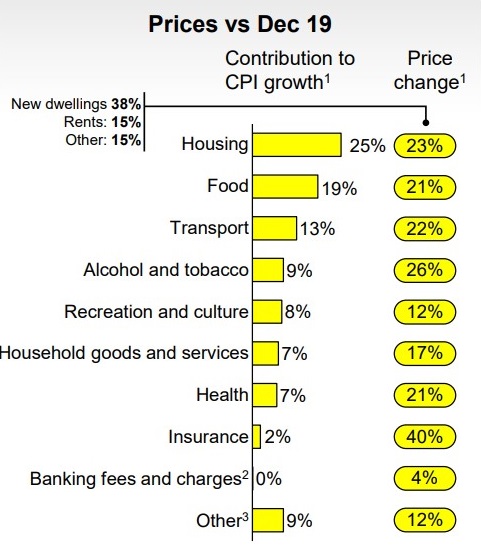

However, the measure of inflation does not truly reflect the surge in the average price of dwellings (the entry price) which is weighted to mortgage servicing costs, rents and maintenance. Inflation measurements, particularly related to housing costs, do not capture the true cost stress confronting families. Clearly, the cost of living for a young family is far different to that of a mature retiree. A bland CPI cannot capture this.

To quote the ABS on its measurement of inflation:

“The CPI is designed as a measure of inflation experienced by households, rather than a measure of the cost of living … Housing is a significant component in the CPI contributing over 22% of the weight of the basket. This includes spending on new dwellings, rents, utilities, maintenance and repair of dwelling and property rates.”

With the compounding of housing prices, the cost of housing and therefore living, has and will continue to rise dramatically for each successive new entrant into the housing market. Therefore, as housing becomes increasingly unaffordable, it is near impossible for statisticians to truly measure the cost of housing, either inside an inflation reading or in a cost-of-living index.

Source: CBA FY24 Results Presentation

Young families are increasingly confronted by a rising housing market and there is evidence that they are adjusting their life choices accordingly. The starkest adjustment has been the decline in the birth rate. Offsetting this has been the decisions by Government and bureaucracy to increase immigration. These decisions have ensured that excessive demand is sustained for housing. This is just one example of the growing divide between political necessity and sensible public policy settings. It exemplifies why a national bipartisan housing policy needs to be urgently created to deflate the housing bubble that has been created.

Political incumbents have bathed in the creation, adoption and support of policies that have driven house prices higher. Their focus is towards those that will support them into Government. There are more debt free house owners than mortgaged owners. Rising house prices are positive for owners and will attract their votes. Governments struggle to contemplate or espouse housing policies that may upset this wealth bucket – even if it is for long term benefit and sustainability of society.

The failure to develop policies to address housing affordability and the cost of living, has resulted in a voting shift away from the major governing parties. Minority governments, driven by populism rather than pragmatism, could develop.

There is an overwhelming need to develop a bipartisan national policy for ensuring stable and sustained housing affordability. The following are my thoughts and suggestions to start the process.

How to rebalance our housing market

So, what can be done to stem house price rises and to rebalance the housing to income ratio? How to develop a viable rental market where rents are not driven by excessive leverage?

Australia needs an agreed national housing policy set with a bipartisan approach. A policy that targets agreed outcomes. The affordability of housing, based on sustainable multiples of average income, should be set. The policy needs to address the rental market to make it sustainable for low-income earners over the long term.

Housing policy needs to develop from a proper review and with inputs coming from across society. It cannot be limited or directed by political or bureaucratic thought bubbles.

It first needs an admission that our housing policy has been wrong for many years. It needs an acknowledgement that rectification with be costly and painful.

We need to accept that the housing price bubble needs to be deflated by a managed policy rather than a future market implosion.

My suggestions are broad ranging. Some have already been canvassed in debates, some have already been mildly adopted, whilst some are radical and controversial. All are designed to check housing prices and create a sustainable rental market for low-income earners.

- Remove lenders mortgage insurance. Banks use this policy to increase the loan-to-value (LVR) for borrowing but insure their risk not the borrowers. Higher LVR’s allow higher gearing, which drives further heat into the market. If lenders are willing to take higher LVR risk, then they can put up the capital to do so.

- Restrict foreign - non-resident – ownership. Now belatedly adopted by the Government from 1 April.

- Slow immigration consistent with rebalancing housing market demand and drive immigrated skills towards the supply of housing.

- Agree a national housing building target allocated across the states with penalties (less GST) for non-performance. Local Government and State Governments need to urgently review planning rules. The majority of demand is unmet in areas with appropriate public transport and other infrastructure. Artificially suppressing density drives families into more remote locations which results in higher transport and living costs.

- Target low income and income support housing developments. Create Public/Private ‘build to rent’ infrastructure bonds. Government guarantees will be important to create a stable secondary market for these bonds.

- Support private builders developing mid-range housing. Create a regulated environment for partnerships with superannuation funds incentivised to provide funding (debt/equity) to approved/registered builders. Severely restrict the existence of private builders with thin capital.

- Consider tax changes inside a proper reset of taxation laws. For instance, should rent (paid) be tax deductible for certain people in certain income bands? Should negative gearing be limited to the income of the underlying asset? Can housing infrastructure bonds be created to channel savings towards appropriate borrowers inside a restructured tax system?

- Accept that house prices need to decline for a period (painful) with the Government to take over existing loans from banks that do not meet regulated debt ratios, so that the financial system can adjust without depleting bank capital. A once off opportunity setting a point from which banks will be penalized for future excessive lending.

- Review occupancy laws. One of the contributing factors to housing shortages has been the reduction in people per household, usually divorced families have two houses not one. Planning provisions that prohibit co-living and better use of existing houses constrain supply.

I suspect that there will be many counters and/or responses to the above.

I also expect howls of criticism and that is fine if it is done inside a discussion aimed at achieving an outcome.

Let’s get a policy restructuring started with all thoughts heard and considered. Further, let's accept that it is a policy set for an outcome that will be costly, and which may take a decade to bear fruits. Long-term planning is not an obstacle if a bipartisan approach is taken. The AUKUS agreement is a prime example of an agreed long-term policy – and we are risking hundreds of billions of investment capital, with an uncertain timeline and result. Surely a National Housing Policy would be so much easier to develop.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.