Let’s start with the numbers on life expectancy.

Here’s a very simple example to explain the concepts.

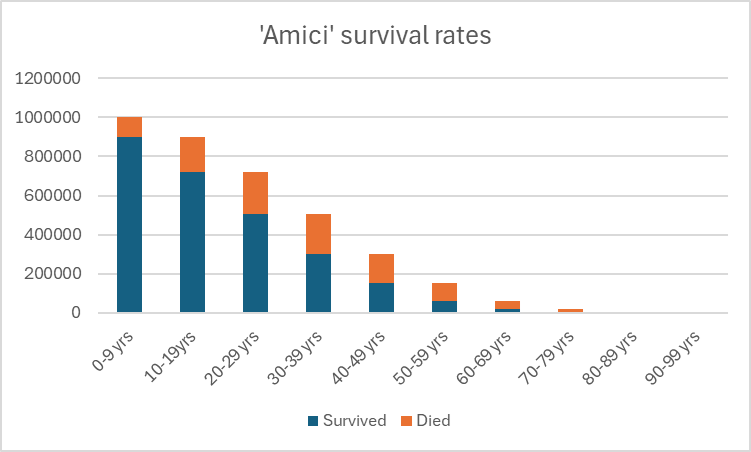

Imagine we arrived a long time ago on a new planet, with a totally different species of life there. We called them Amici, the Latin word for “friends,” because they’re so nice to us. We notice that they don’t live nearly as long as we do on Earth. So we’re curious, and start to measure how long they live. And after many years, here’s what we find.

For every 100 children born, roughly 90% survive to age 10. Of the survivors, roughly 80% survive to age 20. And of those, roughly 70% survive to age 30. And so on. Eventually, of those who survive to age 80, roughly 10% (hardly any of the original group) survive to age 90. And of those survivors, none survive to age 100.

So let’s consider a random group of 1,000,000 new children. In their first ten years, we expect 900,000 of them to survive to age 10, and 100,000 to pass away sometime during the decade. Of those 900,000 we expect 80% of them (making 720,000) to live through to age 20, and the remaining 180,000 will pass away sometime during that decade. And of those 720,000 we expect 70% of them (making 504,000) to survive to age 30, and the remaining 216,000 will pass away sometime during that decade.

And so on. We expect 302,400 to survive to age 40, 151,200 to age 50, 60,480 to age 60, 18,144 to age 70, 3,629 (never mind the decimals, though actuaries invariably use many decimal places) to age 80, 363 to age 90, and none to age 100.

All of that implies 201,600 passing away between ages 30 and 40, 151,200 between 40 and 50, 90,720 between 50 and 60, 42,336 between 60 and 70, 14,515 between 70 and 80, 3,266 between 80 and 90, and 363 between 90 and 100. No need to check the arithmetic: all that’s involved is subtraction.

Those are the implications of those survival rates. What does all that mean for life expectancy?

Well, in the first decade 900,000 Amici live 10 full years. The other 100,000 live somewhere between 0 and 10 years. For simplicity, let’s assume they live an average of 5 years. What’s the total number of years the group has lived? Easy: (900,000 x 10) + (100,000 x 5) = 9,500,000 years.

Similarly, the survivors live 8,100,000 years in their second decade, and in successive decades the survivors notch up 6,120,000, 4,032,000, 2,268,000, 1,058,400, 393,120, 108,864, 19,958 and 1814 years. Again, just multiplication and addition.

The total number of years lived by the original group of 1,000,000 Amici is 31,602,156 years.

And so the average number of years lived by the members of the original group is 31.6 years. (OK, I’m using decimals here.)

That’s typically called the ‘life expectancy’ of the group.

Life expectancy increases as you age

Remember that the group we’re talking about is that original group of 1,000,000 Amici. And by ‘life expectancy’ we’re really talking about their life expectancy at birth. We don’t mean we expect all of them to live exactly 31.6 years. Of course not! In that case, nobody would ever reach age 40! And we know that 302,400 of the original 1,000,000 will survive to age 40.

Now let’s consider those survivors to age 40. For those 302,000 they’ll live a future 3,850,156 years, for an average of 12.7 more years. So, their average age at death will be 52.7. The reason it’s so much higher than the ‘at birth’ life expectancy is that the other 697,600 have already passed away, most of them long before age 40. It’s those earlier deaths that keep the average at birth as low as 31.6. And the group we’re considering (the survivors to age 40) aren’t the same group as the original 1,000,000 Amici: they’re only a subset of the original group, in fact the long-lived survivors of the original group.

You see, in fact, that the longer that individuals survive, the more select their group becomes, and for the more select group, the higher their average age at death.

It’s the same on Earth! When you read that the ‘life expectancy’ of a group is 80 years, typically what this means is that it’s their life expectancy at birth. The longer they survive, the more select a group they belong to, and the higher their average age at death. For example, considering the survivors to age 60 from that original group as a separate group, it may be that their average age at death would be 85 rather than 80. So their average future life expectancy, from age 60, would be 25 years.

That’s why the stand-alone phrase ‘life expectancy’ has no meaning or at least is extremely ambiguous. We might mean ‘life expectancy at birth’ or ‘life expectancy at age 60’, in that example – and we should specify which one we mean.

In fact, it would be better if we never used the expression ‘life expectancy’ at all, for exactly that reason. If we were to say either ‘average age at death, for that group’ (specifying the group) we’d be quite clear. In the example, the average age at death for newborns would be 80; the average age at death for 60-year-olds would be 85. Or we could refer to ‘average future survival years, for that group’ (specifying the group). In the example, the average future survival years for newborns would be 80 years; the average future survival years for 60-year-olds would be 25 years.

What about that Covid effect?

Notice that all those calculations implicitly assumed that the one-year-at-a-time survival rates (90%, 80%, 70% and so on) would continue to apply to all the survivors.

What tends to happen, in fact, is that, over time, survival rates tend to get a little bit higher, as we very gradually have our declines in health later. And so the average future survival years tend to go up gradually.

But Covid intervened to upset that gradual trend. Those survival rates suddenly decreased, as some people died from Covid-related complications. And so, if you assume that those lower Covid-related survival rates stay unchanged forever more, then the average future survival years go down. That was widely reported in 2021 as “plunging life expectancy”, for example in The New York Times.

Well, no, as my post explained. Only if you assume that the higher mortality rates (which is the same thing as lower survival rates) associated with Covid will last forever do the average future survival years decrease (by a very noticeable 1.5 years at birth, in that case). With Covid behind us and mortality rates roughly back to where they were before, the average future survival years are back up again. But do you see that reported anywhere, let alone with the same degree of screaming headlines as the previous effect?

Absolutely not. “You can breathe easily again: if you’ve come through Covid, don’t worry about a shorter average lifespan” doesn’t make for an exciting headline, even if it’s true.

Don Ezra, now retired, is the former Co-Chairman of global consulting for Russell Investments worldwide, and the author of “Life Two: how to get to and enjoy what used to be called retirement”. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.