(Editor's note: as this article went to air, Fletcher Building announced that their CEO and Chair would leave the company this year).

Peter Drucker’s axiom “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” continues to apply, across industries. For investors, if culture is the sophisticated word for execution, market performance has been littered with examples of strong execution dominating market returns.

What Ross McEwan did right

Ross McEwan delivered on culture and strategy for NAB, but if culture is “what we do around here”, McEwan simplified that and made accountability for execution a strong point. Do fewer things but do them well; for example, the number of internal projects being worked on was cut from 467 to 20 when McEwan assumed the role.

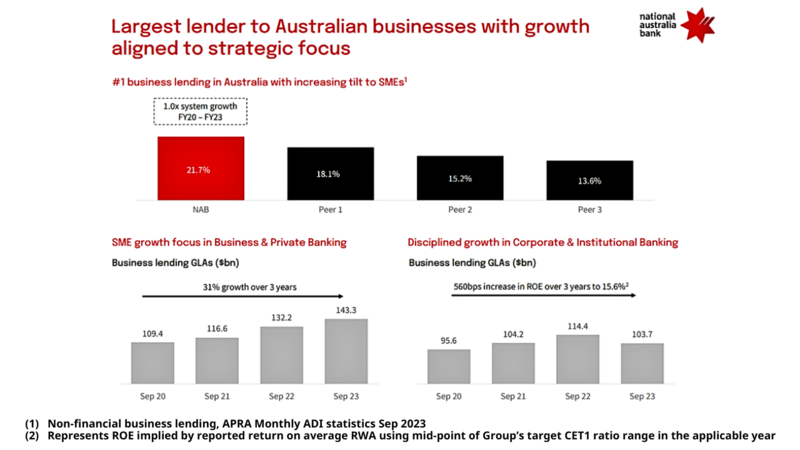

As with Boral, and opposed to Fletcher Building, an implicit cultural recognition arose that for any business with the financial resources that arise when profits in the billions are reported, malinvestment is the silent killer. The result was sector leading performance through McEwan’s tenure, with return on equity nudging that of the long-time leader in the sector, CBA. Indeed, whilst NAB’s market performance is about half of CBA’s through the past five years, since McEwan’s arrival and the focus upon simplification the relative performance gap with CBA has converged.

One senior NAB executive recently highlighted to us that much of the base for the work that has been done during recent years was prepared through the past decade with a complete rewiring of the internal transfer pricing mechanisms within NAB, a project led by the then CFO, albeit that data needs to be used judiciously to be turned to commercial advantage, which has been the change in culture seen through the past four years. When asked what the biggest threat was to NAB after his departure, McEwan nominated “losing focus”, trumping AI, government interference, strategic resets and economic cycles.

Boral has turned things around

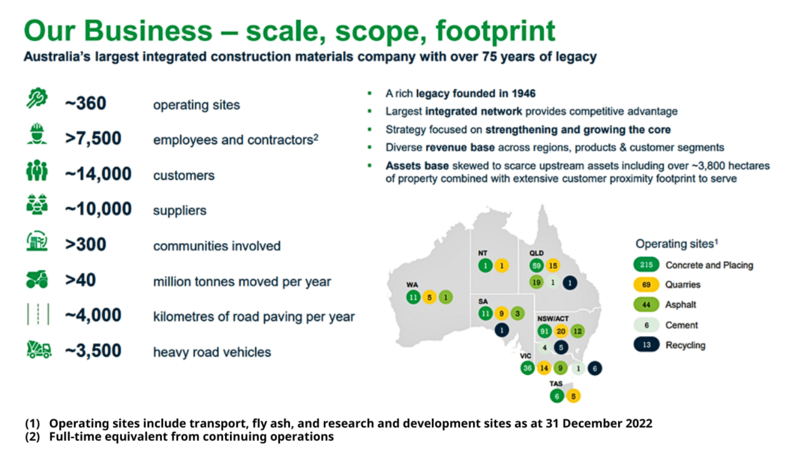

An exemplar of execution through the past year has been Boral. A little more than a year ago, Vik Bansal was appointed as CEO and Managing Director of Boral. In that year, fundamental financial performance changed markedly; revenues up almost 20%, EBITDA up twice that again, and operating cash flow increasing by more than 50%. Repeatedly, internally and externally, 'the Boral Way' is emphasized, speaking to purpose, values, operating model, strategic areas of focus and the pathway to execution. Needless to say, the menu is adopted by many companies, but the focus is often on the former and not the latter elements.

At Boral, since Bansal joined, the focus has been on execution, at a granular level, with the operating model seeing aggressive devolution of authority and responsibility for pricing and volumes, within guardrails, for each of Boral’s 360 operating sites. The CEO spends half of every month in scheduled calls with each of the largest operating sites discussing performance and cashflow performance and requirements. Interestingly, one of the purposes of this is that it is seen as inhibiting malinvestment, especially in grand projects such as ERP systems which are usually expensive, not fit for purpose, do not produce claimed benefits and are soon orphaned vanity projects within the organization which installed them. Mr Bansal claims that managers of operating sites, who will be allocated with the implementation and ongoing costs of such systems, are vocal in opposition to such proposals unless they can see obvious benefit to their asset in terms of the system allowing them to gain market share or charge higher prices.

Indeed, when South32 spun off from BHP, one of the first actions of South32 management was to dismantle the ERP system which had only recently been foisted upon the assets when they were part of BHP, on the basis that the systems were expensive – impeding efficiency – and unduly complicated investment decisions, impeding effectiveness.

Fletcher Building has work to do

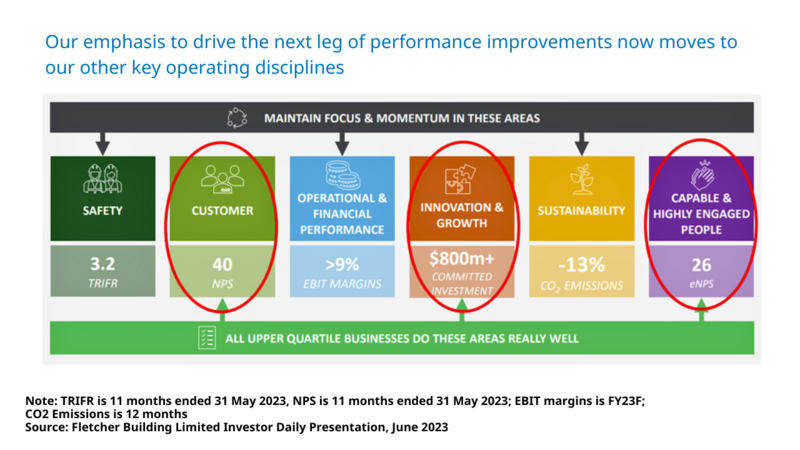

In contrast, another materials company we have held is Fletcher Building. Its performance has been as dire as Boral’s has been stellar. It may be a co-incidence that in just about every observable operating model metric, Fletcher Building has been doing the exact opposite to Boral in recent years. A new ERP system is in the process of being installed across a group which straddles construction, home building, distribution, building products (manufacturing plasterboard and insulation) and concrete businesses.

The better New Zealand assets of Fletcher Building in many ways replicate the product and market positions held by Boral and CSR in the Australian market, and yet the operating performance – before we get to write downs – stands in stark contrast. Centralisation has led to a significantly worse outcome than decentralization, a theme we see persistently across industries. Those closest to the customer usually know best where capital should be allocated to meet the needs of those customers. Whilst New Zealand has had some pressures on end market volumes which have affected operating performance, Australia has had the same headwinds and yet Boral and CSR, let alone James Hardie, have used their positions more adroitly to generate value for shareholders. In sum, it’s not just the whiteboard and strategy that matters (they are often very similar across competitors); it’s in the way that you use it that matters for performance and shareholder return.

Of course, issues other than just sub peer operating performance have materially impacted upon Fletcher Building in recent years. Unfortunately, most of these wounds are self-inflicted.

In July 2017, Mark Adamson left as CEO of Fletcher Building, after a five-year tenure. Months later, Ralph Norris stood down as Chairman. In each case, the changes reflected losses of circa NZ$660m booked through the prior year. Upon announcing his resignation, Mr. Norris wrote that “… Our shareholders place significant faith in me to act in their best interests and expect accountability from the board for all aspects of the company’s performance”.

After years now of further large write offs, overwhelming those that pre-empted the departure of the prior Chair and CEO, there is now neither accountability at Fletcher Building nor murmurings suggesting the acceptance of accountability. Indeed, just through the past year alone, write offs are at NZ$450m, and significant further risk remains in the book on the company’s own reckoning.

This all comes within two years of Fletcher Building spending NZ$273.5m on a share buyback, completed at an average price per share circa 50% above the current share price. At a current enterprise value less than ten times earnings, the value case for Fletcher Building is clear; albeit a steep discount assuming a continuation of reckless operating and financial performance needs to be maintained so long as the current board and management are in place.

Notwithstanding the current malaise, assuming the current board and management will not endogenously or exogenously change in the face of enduring poor performance is stubborn. And at the time of that change, the Boral and CSR lesson is instructive: privileged assets with long lives, managed well, can readily be afforded a multiple circa two to three times Fletcher Building's. As with many other serial underperformers, it’s time for the company board to lose their religion and try a different choir, even with the same lyrics.

Andrew Fleming is Deputy Head of Australian Equities at Schroders, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This document is issued by Schroder Investment Management Australia Limited (ABN 22 000 443 274, AFSL 226473) (Schroders). This document does not contain and should not be taken as containing any financial product advice or financial product recommendations. It does not take into consideration your objectives, financial situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from Schroders, click here.