The decline in interest rates to historic lows in recent years has led to anxiety among Australian investors about what will happen to their fixed interest holdings when overnight interest rates begin to rise.

This apprehension is based on the conventional view that longer-dated bonds underperform in this type of rising interest rate environment.

However, historical analysis of past periods of increasing interest rates in the US and Australia show there is no guarantee that bonds do badly relative to short-dated securities at such times.

In fact, in most of the five distinct periods covered by this study, longer-dated bonds outperformed their shorter-dated equivalents.

The second deduction from this analysis is the reinforcement of the virtues of global diversification in fixed interest. In each period, a globally diversified portfolio of bonds outperformed an Australian-only portfolio.

Thirdly, the experiment confirms that even during periods of rising short-term interest rates, bonds can continue to play a diversification role in a balanced portfolio, reducing overall volatility and expanding investors’ opportunity set.

Background

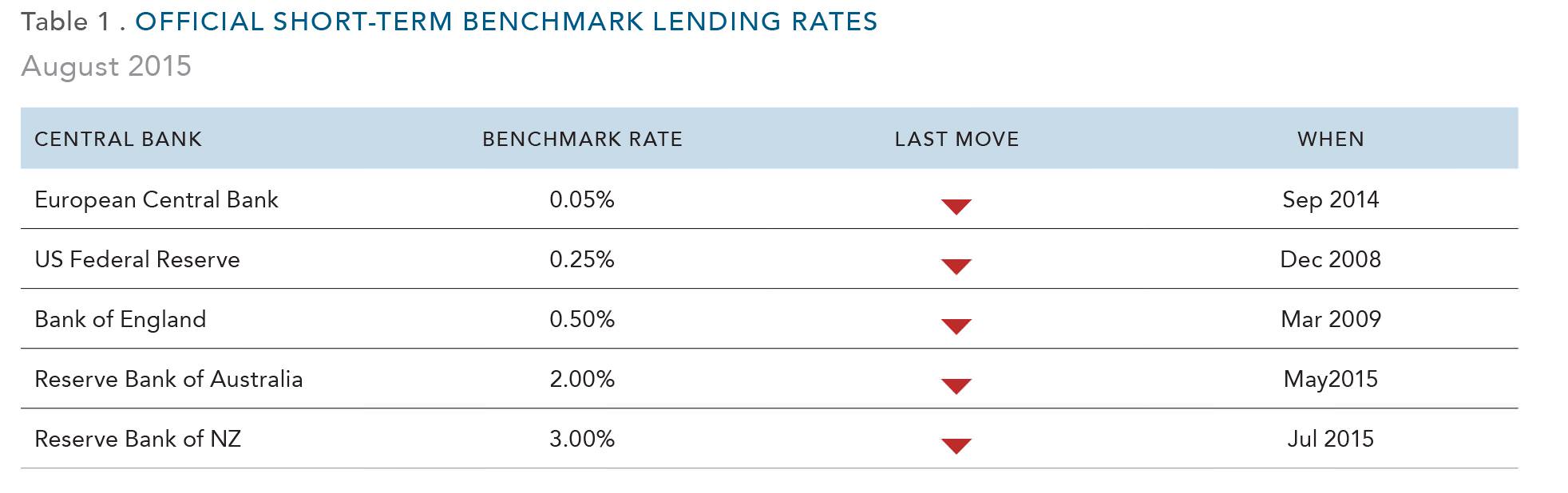

Interest rates and monetary conditions in developed economies have been maintained at extraordinarily easy levels since the global financial crisis as central banks sought to generate self-sustaining recoveries.

A dominant theme recently relates to how and when central banks will start to reduce this level of accommodation and what the impact on risky assets will be. Market sentiment has waxed and waned. Most attention has been on the US Federal Reserve, which has flagged an increase in its funds target rate over the coming months. The rate has been close to zero now for nearly seven years since the peak of the GFC.

The Fed began the process of normalising monetary policy in late 2013, gradually winding back its purchases of bonds. This ‘quantitative easing’ programme added more than $US3.5 trillion to the Fed’s balance sheet over five years.

But central banks elsewhere have shown no hurry to follow. The Bank of England has kept its benchmark at 0.50% for six years. At its August 2015 meeting, just one of the nine members of its monetary policy committee voted for an increase.

The European Central Bank, having resisted quantitative easing for years, began its own programme this year. It is buying 60 billion euros of assets a month in a bid to lift inflation back towards its target of just under 2% by late 2016.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has cut the official cash rate 10 times since November 2011 to 2.0%. With commodity prices falling and inflation pressures contained, the bank has recently indicated that it is in no hurry to raise rates.

Bonds 101

The market values of bonds rise and fall on changing expectations for inflation and interest rates, shifting perceptions about the creditworthiness of individual issuers, and fluctuations in the general appetite for risk.

The yield on a bond and the price of that bond are inversely related. If the price falls, it means investors are demanding an additional return to compensate for the risk of holding the bond.

So if interest rates ‘can only go up’ from current levels, why hold bonds? There are a few points to make in response.

First, it is extremely hard to accurately forecast interest rates with any consistency. Standard & Poor’s regular scorecard shows most managers fail to outpace bond benchmarks over periods of five years or more (Standard & Poor’s Indices Versus Active Funds Scorecard).

Second, outside of the US, there is no guarantee that rates will rise anytime soon. Even in the US, some observers doubt whether the Fed will carry through.

Third, bonds perform differently to shares. Regardless of what is happening with the rate cycle, there is a diversification benefit in holding bonds in your portfolio and making for a smoother ride.

Fourth, each investor’s allocation to the risks associated with bonds, both from a maturity and credit quality standpoint, is an individual decision dependent on each individual’s risk appetite, circumstances and goals.

Finally, if you look at history, it has not always been the case that longer-term bonds have underperformed shorter-term bonds when short-term interest rates are rising.

A case study

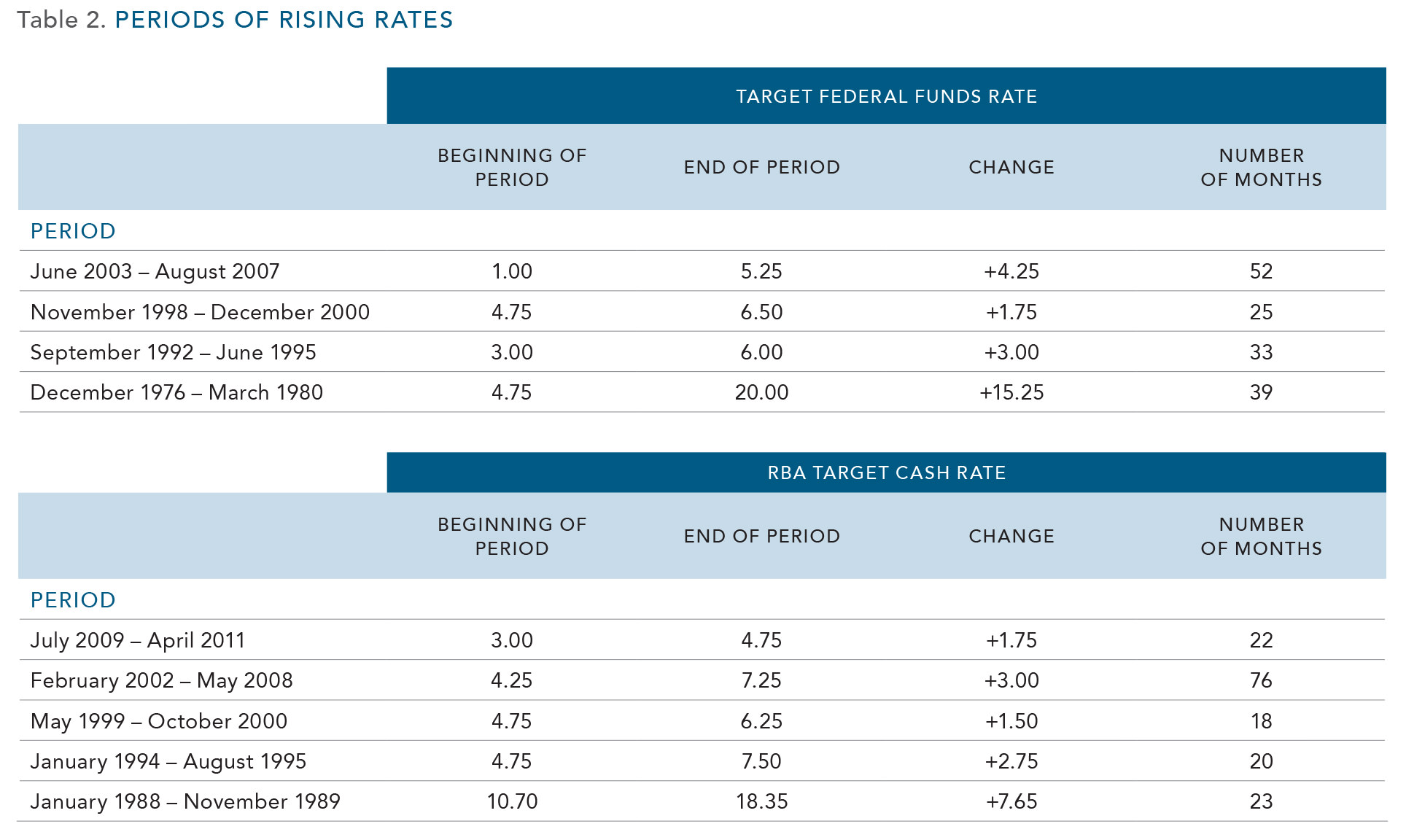

To test that last statement, we carried out a case study of periods of rising rates from the last three decades in both the US and Australia.

To meet the definition of a rising interest rate environment, the increases had to be spread out over 12 months or more and cumulative increases had to be at least 1.5%. Table 2 shows the periods under study.

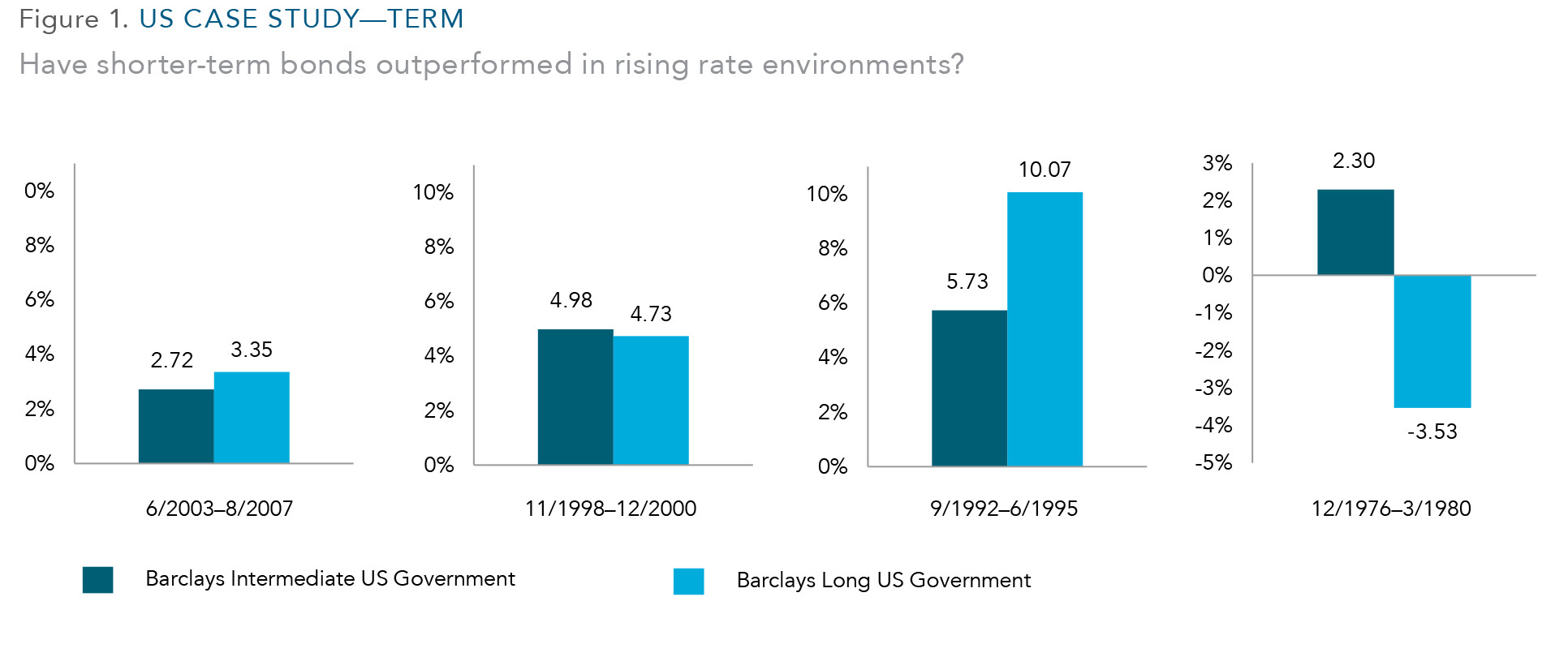

In the US case, using Barclays’ indices, we found that in two of these four periods long-term bonds did better than shorter-to-intermediate-term bonds. In the other two periods longer term bonds underperformed. See Figure 1.

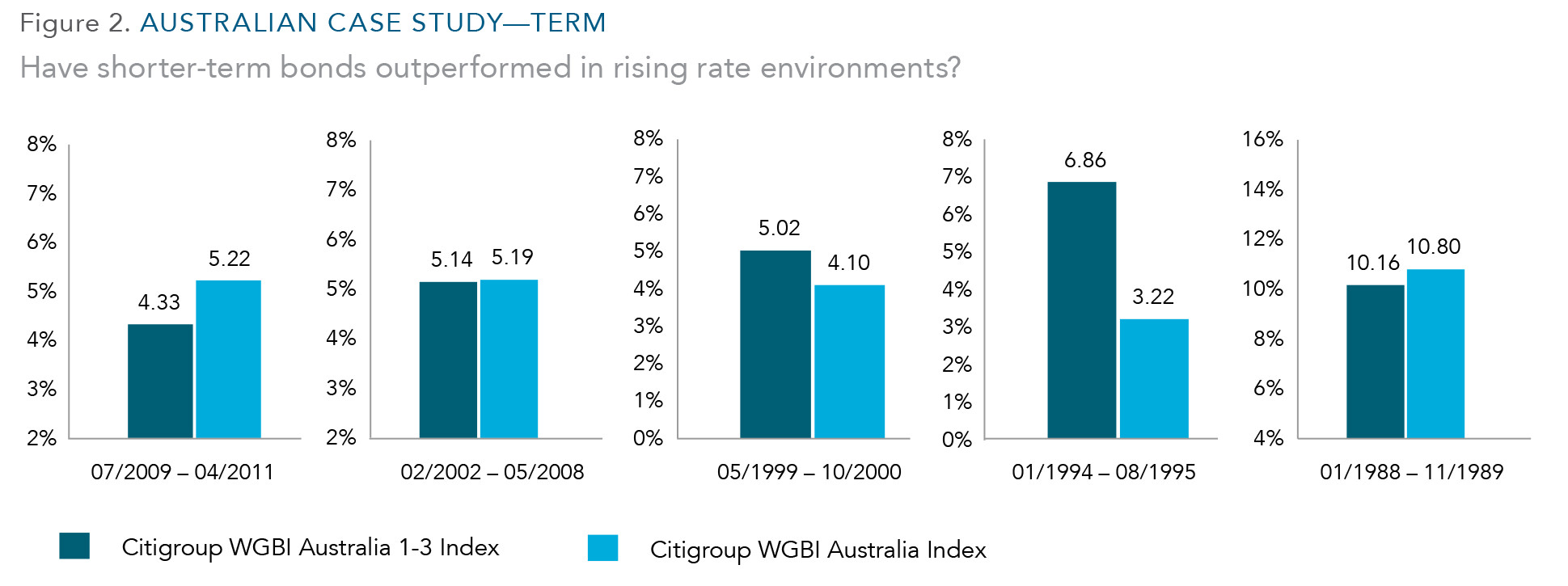

For the Australian case study we used Citigroup World Government Bond indices. Figure 2 compares the performance of Australian Government bonds over the 1-3-year maturity (in blue) and longer maturities (in green).

We can see that the longer-term bonds actually outperformed the shorter-dated bonds during all periods except for the infamous 1994–95 market correction.

Similar results were seen when we compared the performance of a global bond portfolio, hedged to the $A, compared with a domestic-only portfolio.

While this may seem counter-intuitive, remember that longer-term bond holders are often reassured when a central bank is perceived as moving pre-emptively against this threat of higher inflation.

The study also shows bonds continued to provide positive returns, contradicting the often expressed view that rising interest rates are always associated with bond losses. The exception in this study is the late 70s when the longest-term US bonds suffered during a period of very sharp increases in rates.

Summary

Investors are worried about what will happen to their fixed income portfolios when central banks begin normalising interest rates, yet recent decades show longer-term bonds do not always underperform when short-term rates are rising.

In any case, there is no need to forecast. There is sufficient information in today’s prices to base a strategy on. Furthermore, we believe risk can be tempered by diversifying across different types of bonds, different maturities and different countries.

Dr Steve Garth is a Portfolio Manager in Sydney with Dimensional, a wholesale asset manager with more than $500 billion under management globally. This article is for educational purposes and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.