Australia’s $3.3 trillion superannuation system is supposed to boost people’s retirement incomes. The Government says as much in its proposed legislated objective for superannuation. The system is supported by billions of dollars of tax breaks each year, ostensibly to that end.

But there’s just one problem. Increasingly, much of what is saved is never spent.

Our new report, Super savings: Practical policies for fairer superannuation and a stronger budget, points out that without an overhaul, super tax breaks are set to do little more than boost the inheritances of Australians with well-off parents.

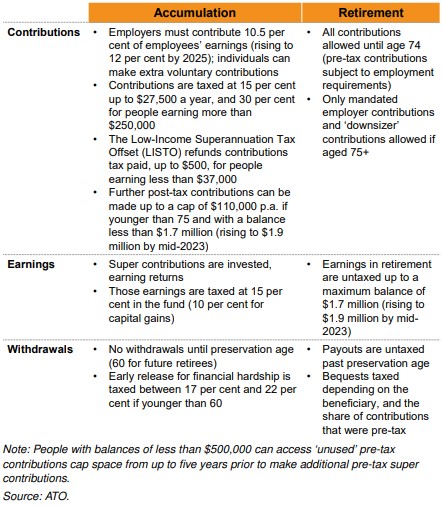

Super contributions and super earnings are both taxed more lightly than other income. These tax breaks cost the Budget about $45 billion (2% of Australia’s gross domestic product, or GDP) each year. Here's a reminder of the major tax concessions afforded to super.

Superannuation benefits from significant tax breaks

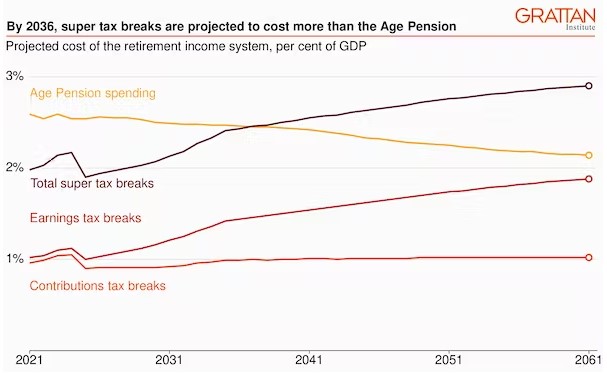

Treasury predicts that the cost to the Budget will hit 3% of GDP by 2060, and that the cost of super tax breaks will overtake the cost of the age pension by as soon as 2036.

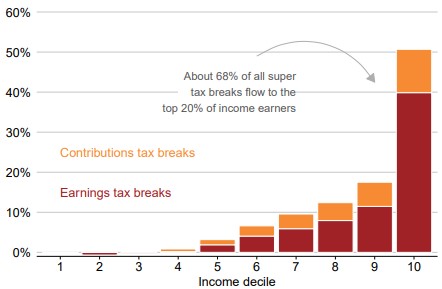

Superannuation benefits favour the wealthy

These tax breaks are not well targeted. Two-thirds of their value benefit the top 20% of income earners, who are already saving enough for their retirement. Retirees with big superannuation accounts pay much less tax per dollar of super earnings than younger workers do on their wages.

Much of the boost to super balances from tax breaks is never spent. By 2060, one-third of all withdrawals from super will be via bequests – up from one-fifth today.

Super has become a taxpayer-funded inheritance scheme. Reining in super tax breaks is a responsible way to boost government revenues in a world where the government has committed to higher spending on defence, healthcare, aged care, and disability care.

Share of total super tax breaks by type and income decile

Governments have supercharged demographic pressures by introducing generous tax concessions for older people. A ‘self-funded’ retiree couple can have, from 1 July 2023, $3.8 million in super, unlimited home equity, and income outside super up to about $66,000 a year, and pay no income tax. The share of households older than 65 paying tax has halved over the past two decades, and average income tax paid has barely changed for people older than 65, despite strong growth in their incomes and wealth.

A reform package to address the inequities

We recommend a reform package that would save the budget more than $11.5 billion a year, including:

- Raising Division 293 tax, which curbs tax breaks to high-income earners on their pre-tax super contributions, from 30% to 35%, and lowering the income threshold at which the tax applies, from $250,000 to $220,000 a year. This would save the budget about $1.1 billion a year and stop many high-income earners benefitting from larger tax breaks, per dollar contributed to their super, than low- and middle-income earners.

- Lowering the cap on pre-tax super contributions, from $27,500 to $20,000 a year. This would save about $1.6 billion a year, mostly by reducing voluntary contributions made by older, wealthier Australians to minimise their income tax bills.

- Abolishing carry-forward provisions and government co-contributions, which were intended to encourage catch-up contributions but in fact facilitate tax minimisation. This would save about $1.1 billion a year.

- Taxing all superannuation earnings in retirement at 15% – the same rate that applies to super earnings before retirement. This would save more than $5.3 billion a year.

- Taxing earnings on super accounts larger than $2 million – rather than $3 million as proposed by the Albanese Government – at 30%. This would save about $3 billion a year, compared to about $2 billion a year under the government’s plan.

The warning signs are everywhere. Australia's current superannuation system is unfair and unsustainable. The reforms we recommend would make the system fairer and the budget stronger.

For more details and background information, see the Full Report.

Joey Moloney is Senior Associate and Brendan Coates is the Economic Policy Program Director and a Fellow at Grattan Institute. This article is general information and not personal advice.