A secret of some investment bankers when selling a company is that valuations can be an advertising tool. If you can’t manage valuations to reach the number you want, you are in the wrong game. The market is perplexed that US company WeWork was worth US$47 billion in an attempted Initial Public Offering (IPO) one week and then US$5 to US$10 billion the next.

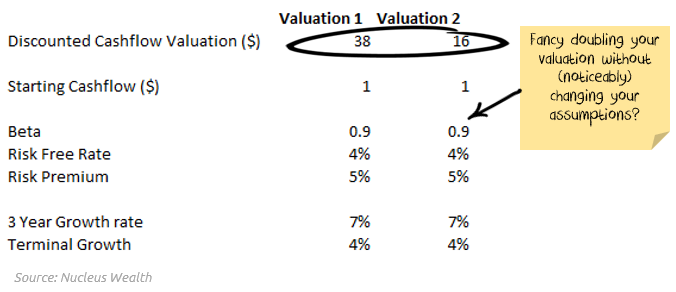

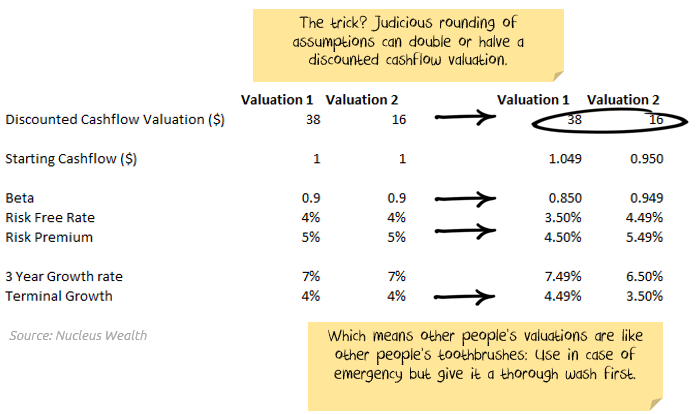

For example, here are two valuations (not of WeWork) that use the 'same' assumptions:

As you can see in the second table, we have hidden as much as possible behind the decimal point:

This table shows how to more than double a valuation by using nothing more than creative rounding of assumptions. Here are more possibilities:

Work backwards

First, choose your valuation. This will save you a lot of time. Ordinary investors put in the assumptions and use the valuation as an output of their model. They use valuations to compare between different companies, assessing which will generate the best returns.

But let’s not beat around the bush. You aren’t here to evaluate investments. You are here to sell an IPO. Start with that number and work backwards to the assumptions to get you there. Besides, your client already knows how much they want to sell the business for.

Comparative multiples

Comparative multiples are where you take several companies and compare them to the company that you want to list. It goes without saying that you want to find the most attractive comparisons.

Some investors don’t like to compare companies with different business models, i.e. service companies versus manufacturers. Some investors note that large companies trade at a premium to small companies. Some investors note that different geographies have different regulatory, competitive or tax environments. Don’t let that bother you. You are going to compare your company to whatever puts it in the best possible light.

Comparison profit measures

The first thing you need to do is to choose a valuation ratio. Only a rookie would want a price to 'reported' earnings ratio. The word ‘reported’ implies audits, signed off accounts and a paper trail. Far better off to go with a non-GAAP / non-IFRS number where you can adjust your way to the valuation you need.

An EBITDA multiple is usually your best option. EBITDA stands for… actually don’t worry about what it stands for – you may need plausible deniability at some stage. Just know Charlie Munger says:

"I think that every time you see the word EBITDA, you should substitute the word ‘bullshit’ earnings."

EBITDA is a non-GAAP / non-IFRS number. Basically, to get to EBITDA, you start with profit and then take out whatever you like. Best way, make two piles: 1) positive things that added to profit and 2) negative things that detracted from profit. Don’t worry about pile 1 – they are all staying in, regardless of whether they are repeatable or not. Your goal is to get rid of as many of the things in pile 2 as you can.

As an example, WeWork created a new term ‘Community Adjusted’ EBITDA – stripping out marketing costs, startup costs, legal costs, share-based expenses and depreciation. Because what company ever needed those?

Sales multiples are a last resort for the genuinely unprofitable companies. The problem with sales is that it is hard to fake.

Time is merely a social construct

The great philosopher Ford Prefect once said: ‘Time is an illusion’. Use this illusion wisely.

WeWork goes for 'run rate revenue', or the most recent month times 12. You are only as good as your latest hit, right?

You can also mix and match time periods to suit. Most respected analysts compare time periods that match, re-adjusting balance dates in order to make a fair comparison. No reason that should apply to an investment banker’s comparison.

Does your company have irregular costs and revenues? Think about changing your balance date. Maybe you can banish negatives into 'the year before last'. And who cares about what happened in such a distant past.

Pro forma accounts

Pro forma sounds way more technical than 'made up accounts'. But they are. Don’t forget the woulda/shoulda/coulda adjustments. These aren’t the actual profits, they are the profits that woulda/shoulda/coulda been if everything was always perfect and nothing ever went wrong.

Did the company shut down anything recently? Allocate any cost you possibly can to that closed-down division. Then remove it entirely from the accounts except for an obscure footnote.

Spin-offs and tax decisions

If you are spinning off or selling a subsidiary of a foreign company, you will need to get the accounts redone.

Start with the reports you presented to the local tax authorities and get all of the assumptions the company made to create the accounts.

Then, simply change every assumption to the exact opposite. Depreciating assets over three years for the purposes of tax? Better to spread that out over 10 years for the market. Charging interest rates of 9% back to your closest tax haven? Pretend it was 2%. Expensing R&D? Better to capitalise R&D before you list and let shareholders worry about the depreciation after you have sold the company.

In fact, capitalise anything you can get your hands on for prior years – interest expenses, software, customer databases, whatever you can. If you are really sneaky, you might be able to slip in a write-down of all of those things before listing. But if you can’t, don’t worry too much. Once you have sold the company, they will be someone else’s problem.

Final adjustment to comparables

Now that you have a number to compare with the company’s competitors, you can start finding the comparables.

Median, market cap weighted average, straight average. There are good reasons why real investors use one rather than the other. Calculate them all and take the maximum. Or minimum. Whichever. Getting closer to the number you want is what’s important.

And remember pile 1 and pile 2? This is a great place to hide adjustments. The smarter investors will be busy checking all of the modifications you have made to the earnings of the company you are listing. But even intelligent investors will often forget to check the adjustments you make to comparable earnings. Don’t let this opportunity pass you by.

Discounted cashflows

I have already shown you how to double a valuation using no more than the rounding of your assumptions.

Discounted cashflows are far more 'flexible' than comparative valuations. First, they are in the future, and so you can make up pretty much whatever you want.

They are based on free cash flow. A glorious term that has many competing definitions, and so use whatever you want. And best of all there are so many places like risk-free rates, risk premiums, beta, short-term growth rates, long-term growth rates that can all be used to tweak a valuation up or down.

Wholesale and accredited investors

Another great term. The marketing department deserves congratulations on creating these.

Basically, wholesale and accredited investors think they are getting 'special access' to deals that regular investors can’t. What wholesale and accredited investors are really getting is access to a deal with far fewer legal protections around things like the truth and fair comparisons.

Final word

Make sure to use all of the tools at your disposal.

If you bury your integrity in one grave, it is too easy to discover and too disturbing when it is found. If you scatter the remains of your valuation’s integrity far and wide, then you will have more chance of slipping through.

Damien Klassen is Head of Investments at Nucleus Wealth. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual. The examples do not reference any particular company.