After 40 years of writing memos to his clients, Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital realised he had never written about selling. It’s surprising given the impact of the sales decision on investment results, and in particular, missing out on subsequent market gains.

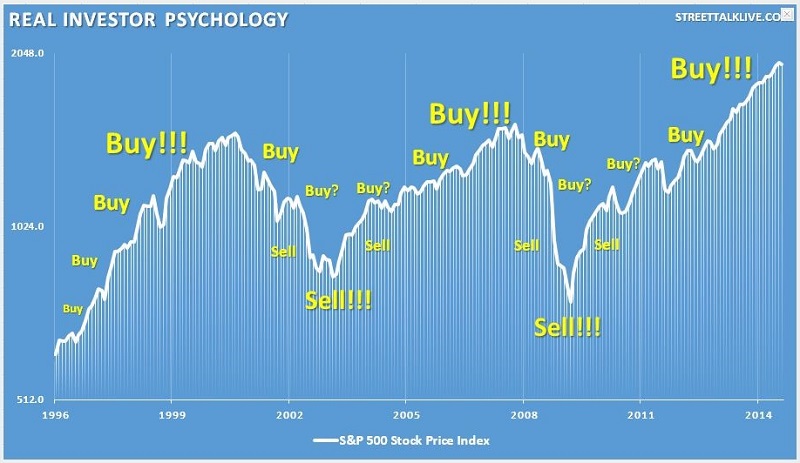

Numerous studies show the average fund investor performs worse than the average fund, and it’s mainly due to the entry and exit decision. Here is a typical chart which I often use during investor presentation, and while it might be exaggerated, there’s much truth to it. Inflows to funds tend to be at their maximum after a strong run and a market peak when investors are confident. Fewer people have the fortitude to buy after a sell-off, and worse, they sell because they fear further falls. This ‘buy high, sell low’ attempt at timing is rarely successful.

Marks cites Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, who notes that selling based on market timing gives an investor two ways to be wrong: the decline may or may not occur, and if it does, when is the time to reinvest?

Marks notes that the people who sell before a market fall and “too often may revel in their brilliance” but then they fail to reinvest at the market lows, so what did they achieve?

Who can hang on faced with big gains or losses?

Marks uses the classic example of buying Amazon to show how tough it can be hanging around for the long-term results. Amazon floated in 1998 for US$5, and it’s now US$3,304 (up 660X). But it hit US$85 is 1999, or 17X in less than two years, so who would not have been tempted to sell then? By 2001, it was down 93% to $6, so who would have panicked? And by 2015, it was back to $600, or 100X the price of 2001. Selling at a wonderful $600 would have missed 82% of the subsequent rise. Says Marks:

“When you find an investment with the potential to compound over a long period, one of the hardest things is to be patient and maintain your position as long as doing so is warranted based on the prospective return and risk. Investors can easily be moved to sell by news, emotion, the fact that they’ve made a lot of money to date, or the excitement of a new, seemingly more promising idea. When you look at the chart for something that’s gone up and to the right for 20 years, think about all the times a holder would have had to convince himself not to sell.”

Investing is a relative selection

Many investors sell when a share price rises because they do not want to lose the profit. Nobody enjoys seeing a big gain disappear. But likewise, many investors worry about allowing losses to compound. It’s bad enough when a stock loses 10%, but letting it go further to 20% or 30% seems neglectful. So markets up, markets down, investors tend to overtrade.

Marks is keen on an idea taught to him when he first started in the market by a mentor, Stanford University Professor Sidney Cottle, that all investing is a ‘relative selection’. Marks says:

“Selling an asset is a decision that must not be considered in isolation. Cottle’s concept of ‘relative selection’ highlights the fact that every sale results in proceeds. What will you do with them? Do you have something in mind that you think might produce a superior return? What might you miss by switching to the new investment?”

And so despite the risk of market falls, Marks says the most important thing is ‘simply being invested’. Buying and selling based on market timing is not likely to work and misses the potential for upside.

Backing his view, he cites data showing long-term returns from markets and the risk of missing out on a few days. In particular, anyone starting out investing as a young adult will do well by the time they retire. For example:

“JP Morgan Asset Management’s 2019 Retirement Guide showing that in the 20-year period between 1999 and 2018, the annual return on the S&P 500 was 5.6%, but your return would only have been 2.0% if you had sat out the 10 best days (or roughly 0.4% of the trading days), and you wouldn’t have made any money at all if you had missed the 20 best days. In the past, returns have often been similarly concentrated in a small number of days. Nevertheless, overactive investors continue to jump in and out of the market, incurring transactions costs and capital gains taxes and running the risk of missing those ‘sharp bursts’.”

One of the basic tenets of investing

Marks says that when the five founders of Oaktree established an investment philosophy in 1995, one of the six tenets focussed on market timing and inability to predict markets:

“We keep portfolios fully invested whenever attractively priced assets can be bought. Concern about the market climate may cause us to tilt toward more defensive investments, increase selectivity or act more deliberately, but we never move to raise cash. Clients hire us to invest in specific market niches, and we must never fail to do our job. Holding investments that decline in price is unpleasant, but missing out on returns because we failed to buy what we were hired to buy is inexcusable.”

I would qualify this by acknowledging that the portfolio should participate in the upside but not carry so much risk that the investor cannot sleep at night worrying about losses. Too much focus on preparing for losses is a mistake but there is no one-size-fits-all in investing. Many retirees simply cannot tolerate losing the money they have to live on when there is little or no capacity to return to work.

Marks’ bottom line

Howard Marks sums up his latest memo saying there is no ideal portfolio and no complete way to assess risk. Therefore:

- We should base our investment decisions on our estimates of each asset’s potential

- We shouldn’t sell just because the price has risen and the position has swelled

- There can be legitimate reasons to limit the size of the positions we hold

- There’s no way to scientifically calculate what those limits should be.

“In other words, the decision to trim positions or to sell out entirely comes down to judgment, like everything else that matters in investing.”

Graham Hand is Managing Editor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.