"A lot of people die fighting tyranny. The least I can do is vote against it."

- Carl Icahn

Capital markets have been wonderful inventions. Freed from self-interest and patronage, they allow Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ to unemotionally allocate scarce capital around the economy, investing where it will be most productively used. Society as a whole reaps the benefits. Greater economic output raises living standards for all. Better investment returns benefit retirees and those planning for retirement.

These days capital markets are heavily-regulated structures. They should be. Despite their capacity to turbo charge economic growth, capital markets have significant flaws. Some of these shortcomings are plain to see. Wealthy and compassionate societies don’t let market forces decide whether an ambulance arrives.

We set the boundaries that markets operate within because we know there are many problems that markets can’t solve. For the problems we do want them to solve, however, capital markets can still fall well short, often at the great expense of investors.

The agency problem

The original sin within our model of capitalism is that it separates the ownership of companies from their management. Few family-owned businesses can attract the capital or talent necessary to build a BHP. Thus, by separating the ownership of a company from its management, businesses are able to grow - and create wealth and jobs - in ways private firms struggle to replicate.

In doing so, we create what economists call an ‘agency problem’. Investors, who put up their hard-earned savings and own the company, must rely on their agents - management - to run the business with the owners' best interests in mind.

Managers on the whole are an honourable breed. But, as Paul Keating liked to say, quoting Jack Lang: ‘In the race of life, always back self-interest - at least you know it's trying.’ Time and again, left unsupervised, managers have demonstrated a terrible tendency to run companies in ways that suit them, not their shareholders.

Our solution to this agency problem is supposed to be robust and independent company boards. Shareholders appoint directors and pay their salaries. They are there to act as the guardians of our capital and to stand up to managers on our behalf.

The ‘Wall Street walk’

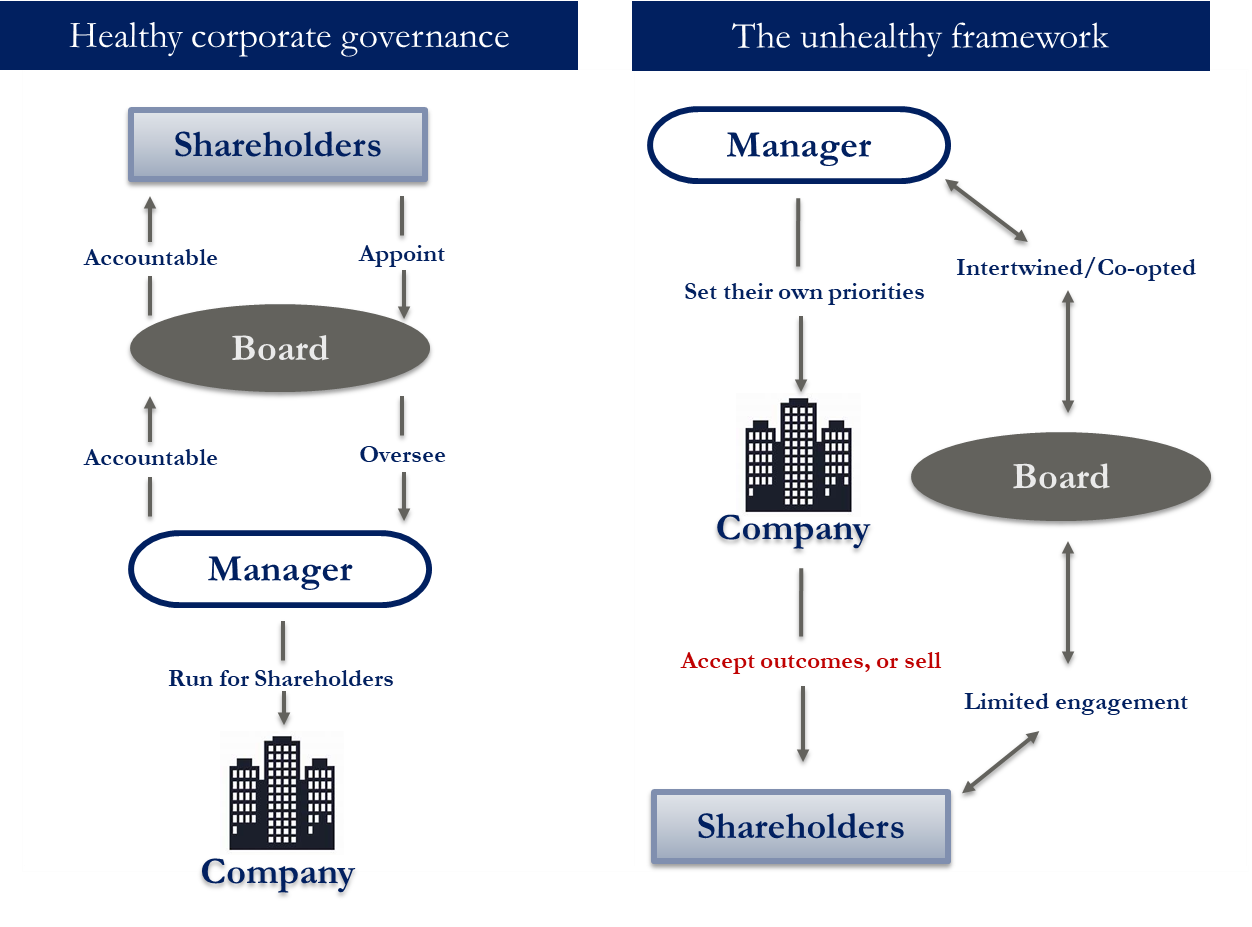

The entire premise of shareholder capitalism rests on the notion that a board is there to represent shareholders. When the relationship is working well, a company’s corporate governance framework should look like the healthy model below.

Shareholders appoint directors who, in turn, oversee management. Boards are there to offer advice to management when it is needed, and to hold them to account when it is necessary. Management then have a clear guiding principle to work towards - prioritise shareholders and shareholder returns.

Well-functioning corporate governance models look great in textbooks. In the real world, modern capital markets have left shareholders increasingly separated from the boards that are supposed to represent them.

Shareholders come and go today with incredible speed. In the 1960s, the average share holding period for a US investor was six years. By the 1990s, this had fallen to just two years. Today it sits at six months. While a company’s owners come and go every few months now, boards and managers work together hand-in-hand for years, sometime decades.

It is easy to see how boards can become co-opted by their management teams. Almost all ‘shareholder feedback’ today comes to boards through the manager and the manager’s investor relations team.

When was the last time you directly spoke to the board of a company you owned?

Even with the best of intentions, boards are at risk of receiving curated shareholder feedback that fits with managements’ own agenda.

In the real world, the most common corporate governance failing at a company is that its board slowly becomes entwined with its management team. Managers then begin to set their own priorities for the company and their own vision for the future. Sometimes these overlap with what is best for shareholders. Too often they do not.

When this occurs, shareholders - who are the owners of the company - are left with two options. Accept the outcomes that management deliver or sell your shares and move on. In market parlance this second option is referred to as the ‘Wall Street walk’.

The passive problem

Exacerbating the agency problem in recent years has been the explosive growth of passive investing and the Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) industry. The premise behind passive investing is hard to fault. ‘Efficient market theory’ argues that everything you could ever know about a stock is already in its price. Given that, don’t bother trying to analyse companies.

Instead, let others do the hard work of figuring out what a company is worth and passively invest into the markets as a whole. This logic is certainly boosted by the fact that, after fees, the average fund manager underperforms the market over time.

While ETFs have provided many investors with a great low-cost way to invest in the market, they have amplified the agency problem that already existed in the stock market. As the share of companies owned by passive investors has increased exponentially, fewer shareholders today are actually involved in the process of holding managers and boards to account.

Vote with your hands, not your feet!

When shareholders feel that the Wall Street walk is the only way to escape an underperforming company, the entire premise of how capital markets are supposed to work has broken down. The point of public companies is that public scrutiny and shareholder democracy is there to shine a light, to hold the people working for us to account.

If shareholders do not exercise those rights, self-interest and cronyism very quickly sets in. Worse, the cycle becomes self-fulfilling. When shareholders vote with their feet and not their hands, vested interests learn a very dangerous lesson. Once learnt, the problems tend to get worse over time, not better.

All of this means that it is more important than ever that shareholders pay attention to what is going on at their companies. If you are a shareholder in a company, you are the owner of the business. Make a point of engaging with your board - they are there to represent you. Most importantly, take the time to vote at shareholder meetings, and if you’re unhappy, vote with your hands, not your feet! You own the companies that you invest into. The people running them are supposed to be working for you.

Miles Staude of Staude Capital Limited in London is the Portfolio Manager at the Global Value Fund (ASX:GVF). This article is the opinion of the writer and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.