When President Trump started his trade wars with China in 2018, Australia's trade relations also took a series of hits from China, as Australia is essentially America's sheriff in the South Pacific. Relations have worsened dramatically in recent weeks, widening the range of exports under threat, from crops, food, wine, coal, to education and tourism (once borders are open).

Heavy reliance on another country

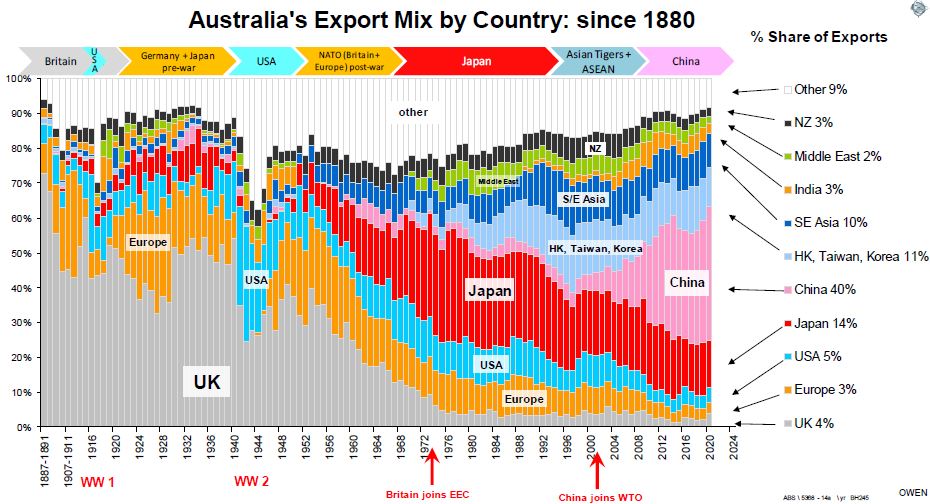

Australia has not been as reliant on one country for export revenues (and tax receipts) since 1953 when the largest buyer was Mother England. China overtook Japan as our largest buyer in 2010, and now accounts for more than 40% of export revenues.

Hundreds of ASX-listed companies rely on Chinese demand, directly or indirectly, across many industries. Iron ore is our largest export to China, and the three main producers BHP, RIO and FMG together make up more than 11% of the total value of the 2,200 ASX-listed companies. These three companies are worth more than the smallest 2,000 listed companies combined. In the latest reporting season to June 2020, BHP, RIO and FMG contributed 41% of all profits reported ($15.8 billion dollars out of $40 billion in total profits).

This chart of Australia's export buyers since 1788 shows the global power shifts over the period, from the UK, Europe, via the US, to Asia. It also highlights Australia's central role in helping to build industrial and economic capacity in a string of Asian nations as they ‘emerged’ one by one along the way – first Japan, then the Asian Tigers, then ASEAN, and now China.

Brief history of trade relations

Trade relations have always been closely intertwined with strategic and military relations. From 1788, Australia started out as a string of British prison colonies that turned into suppliers of oil, wool, grains, food, gold and other metals to Britain as part of the British trade bloc, protected by the British Navy.

After Federation, Australia rapidly increased its exports to Germany, helping build its industrial and war machine for WWI. When war broke out, our exports to Germany ceased and the US took over. In the post-war reconstruction, Australia again increased exports to Germany, Italy and Japan, assisting in their industrial and military build-ups to WWII. When war broke out again, exports ceased and America again came to the rescue to win the war, and it again filled the gap in taking Australia's exports. Likewise in the Korean War.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Australian exports boomed in the reconstruction of Western Europe as a US ally against communist USSR. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, Australian coal, iron ore and other metals helped build the rebirth of Japan, as a US ally against rising Communist China following Mao's revolution in 1949.

After Japan's growth ended in the early 1990s, Australia's mineral exports helped to build the next breed of rapidly expanding ‘emerging markets’ – first the ‘Asian tigers’ (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan), and then the ASEAN countries including Malaysia, Taiwan, Philippines and Indonesia.

China is the latest ‘emerging’ nation built with the help of Australia's exports. Before China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001 it bought just 5% of our exports, but the WTO entry kicked off its incredible urbanisation and industrialisation boom. The key ingredient was, and still is, steel made mainly from Australian iron ore and coking coal. Our rocks and dirt are building not only the gleaming new Chinese cities and railways, but also the war machine it may use against us one day, just as we supplied Germany, Italy and Japan in their military build-ups to the two World Wars in the 20th century.

China's extending ambitions

We are not at war yet of course nor are we even close. What we do know is that President Xi Jinping has extended China's national ambitions well beyond Mao and Deng’s vision of China to simply regain its pride and standing in the world after two centuries of foreign domination and impoverishment. China has achieved that and is now flexing its economic, political and military muscles to extend its power across the region and also into Central Asia, Africa and Latin America in search of markets for its products, sources of raw materials, and strategic alliances.

What is also evident, is that there is a global military build-up brewing, not only in China and the US, but also involving key allies like Japan, and also other players like Russia and a strategically resurgent Europe. This will be good for Australia's miners.

Hopefully, there will not be a major military conflict for many years or perhaps even decades, but as tensions build, China has slapped tariffs and restrictions on several non-critical imports from Australia. This is partly to punish Australia (for supporting the US on Huawei, etc.) but also partly as a show of power, and partly to genuinely help its local suppliers that have been hurt by the coronavirus restrictions and recession.

The industries affected so far are non-critical to China. However, in the case of economically and strategically critical iron ore and coking coal (for steel), China knows that it is still heavily reliant on Australia. China has been actively trying to develop alternate suppliers for several years, both internal and external, but with little success to date.

Hypothetically, in the event of war (e.g. China-US), if we were still a US ally at the time, our exports to China would cease immediately. In practice, China would probably move to act much earlier and restrict supplies to weaken Australia's resolve and test its alliance with the US.

China has been buying up Australian companies outright for several years, and also buying up stakes in many listed Australian companies. It is already the largest shareholder in RIO, FMG and numerous other miners and exporters. This trend is now being countered by more assertive government restrictions on Chinese investments, on the grounds of ‘national interest’.

Would the US fill the resultant export revenue gap if China were to stop buying from Australia? It depends on the importance of the export. It would be an ideal bargaining chip for Australia as a condition of our military support in a conflict (as Menzies was able to achieve in the Korean War).

Trade tensions strike home

All of this is well into the future of course, but we can see the wheels turning. This latest escalation in trade tensions appears to have finally struck home to CEOs and boards of Australian companies that they urgently need to diversify their revenue sources away from the heavy reliance on China. Developing new markets is expensive and time-consuming, especially with the current global travel restrictions.

It will probably mean companies retain more of their earnings for reinvestment in developing new markets. This would require a major reversal of the current shareholder demand for high dividends and minimal reinvestment for the future.

What is the relevance to investors? Aside from the further likely disruptions to hostile trade actions (which are outside the control of companies), we should also expect (and like) to see more companies reinvest more of their profits to develop new markets. This would mean lower dividends in the short term but potentially greater growth in profits and dividends, and diversification of revenue sources, in the medium to long term. It would also probably mean fewer windfall gains to investors from Chinese takeovers of local companies.

It is also a reminder of the importance of investing in international share markets, where the risks and potential rewards are more diversified than on the local Australian market.

Ashley Owen is Chief Investment Officer at advisory firm Stanford Brown and The Lunar Group. He is also a Director of Third Link Investment Managers, a fund that supports Australian charities. This article is for general information purposes only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.