In a monthly column to assist trustees, specialist Meg Heffron explores major issues relating to managing your SMSF.

Nothing bad happened to super in the October 2022 Federal Budget despite many predictions about possible changes to tax laws, limiting funds to $5 million and the like.

But the fact that those things didn’t change in October doesn’t mean they won’t be on the agenda in May 2023. It seems to me that most new governments treat their first budget as an opportunity to exclaim with horror that the cupboard is bare so “tough decisions will need to be made” and lock in some funding for their top election commitments. Everything else gets left for the next budget so they can enjoy their honeymoon period.

That means we should be thinking ahead to May 2023 – what’s likely then?

Might that be the time when we see something designed to break up very large SMSFs gain some traction? What could that look like?

Who would be impacted?

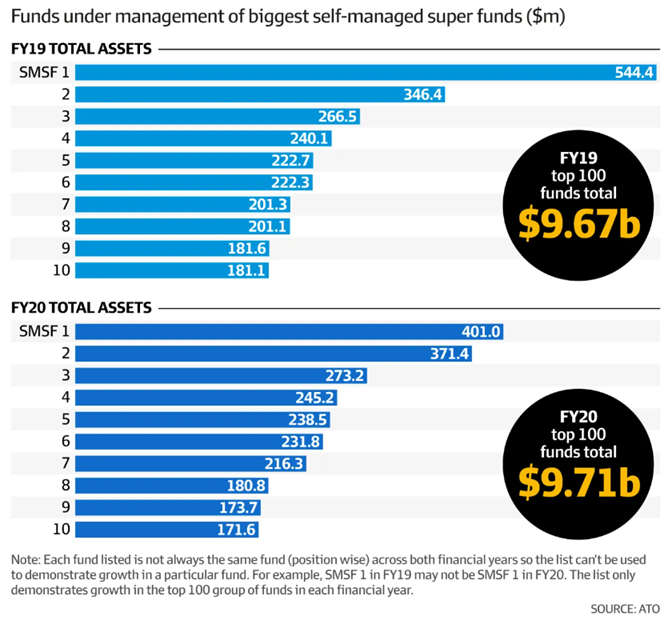

There are certainly some enormous SMSFs. For example, in August 2022, the AFR quoted values for Australia’s three largest SMSFs as $401 million, $371.4 million and $273.2 million. And 32 SMSFs had more than $100 million. That’s some very large funds.

Using the latest ATO statistics (which are based on returns for the 2019-20 financial year), there are very roughly 600 funds that have more than $20 million. Since most SMSFs have two members, that’s $10 million each. Again, a lot of money.

And all the investment income earned by those funds is being taxed at 15% (at most). Presumably the people who belong to these very large funds would pay much more tax if they had to take their money out of super. So not surprisingly, there are loud calls for us (as a community) to spend less money on providing generous tax concessions to people in this position.

But is the answer a hard limit on size? I’m not sure that’s a great plan.

For a start, if there is a limit at all it should be at a member level – not a fund level. So a fund with twice as many people should be allowed to be twice as large. And obviously it should apply to all super funds, not just SMSFs. Even with those adjustments, is a hard limit on member balances the way to go?

There are a couple of reasons I favour an alternative – and I’ll explain one shortly.

Eventual demise of extremely large funds

Let’s remember that this isn’t necessarily a long-term problem in any case. A few factors will drive these very large funds to dissolve of their own accord in time.

The one thing that forces all of us to take money out of super eventually is death. For the majority of people who die, the only amount of their super that can stay in their fund is whatever their spouse is able to take as a pension. If he / she can’t take it all as a pension it has to come out of the fund as a lump sum. And this is where the $1.7 million transfer balance cap plays a role – it limits the amount that can be taken as a pension, indirectly forcing money out of super whenever someone with a large balance dies.

These days, there is a limit on virtually every type of super contribution that can be made (personal injury settlements are the one exception – and I expect no-one would begrudge someone creating a $10 million SMSF if they received $10 million in a compensation payment for a terrible injury). In short, these days it’s virtually impossible to put enough money into super to grow a balance to the current dizzying heights of these very large funds. That means most of these very large funds have probably been around for a long time and perhaps have members who are getting older.

So here’s my first hypothesis – I bet a lot of these large funds have two members and both are in their 70s – 80s. As soon as one of them dies, the fund value will fall dramatically. And that’s without any change in the law.

And my second hypothesis – the rest of us stand no chance of getting there because we won’t be able to put enough into super to make it happen. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if we see the number of funds with balances in excess of $20 million fall dramatically in the next 10 years but the number with $1 million - $5 million increase as those in their 40s and 50s approach retirement. We’ve had the benefit of compulsory super for most of our working lifetimes but by the time we were able to really focus on our retirement savings, contributions were very tightly controlled.

Is change really needed?

So, is this a problem worth compromising the current simplicity for or will it go away on its own?

If your view is still firmly in the 'reign in tax concessions for the wealthy', I wonder if there are better alternatives than a hard balance cap.

There was a time (before 2007) when it was compulsory to start taking money out of super at a certain age – for most people it was 65 (a little later for people who were still working but let’s work with 65). At that point it was compulsory to turn all of one’s super balance into a pension or take it out of the fund entirely. Funnily enough, removing this rule (called “compulsory cashing”) back in 2007 is probably one of the things that has allowed these mega funds to stick around for so long – there’s simply no requirement to take the money out before death anymore.

What if we went back to some form of compulsory cashing and it became compulsory for everyone to start drawing down on super at some point?

The challenge these days would be that there’s only so much anyone can move into a pension (the transfer balance cap strikes again). And I’m not an advocate of forcing everyone with more than $1.7 million to take every other dollar of their super out as a lump sum immediately. Imagine the potential for investment chaos, fire sales of assets etc.

Rather, what if we had a second class of pension that didn’t get all the same great tax perks as a modern day “retirement phase pension” but with no limit on size? Perhaps the investment earnings on the money in these pensions could still be taxed as if the money was in accumulation phase – whereas no tax is paid when money is in a retirement phase pension? In fact, we already have a pension that works this way – transition to retirement pensions for people who are under 65 and haven’t yet retired.

Or perhaps the earnings on money in these pensions could be taxed at an even higher rate than 15%? Or perhaps the drawdown rates could be higher, so the balance is forced out of super faster than a traditional pension. I’m sure we could be imaginative here.

The key is that something along these lines would force all who hit the magic age to start drawing down on their super in some way. But they could do so steadily over time rather than all at once.

It would also mean we’re not imposing arbitrary limits on balance sizes – any government that does this can expect immediate challenges. There will be calls for leniency in times when markets are volatile (… all the time), protests of unfairness for those who cashed out large super balances only to see their assets plummet in falling markets. There would no doubt be calls for the change to be phased in over time or for some members to be specifically excluded from it (known as ‘grandfathering’). And these requests would be reasonable – those with large super funds have grown them legally, they’ve made long-term decisions about investments and tax. It would be unreasonable for them to be told to change everything ‘tomorrow’.

There will be (perhaps rightfully) cries that the ASX and our property markets will be decimated by large SMSFs offloading millions of dollars as they cash out their members’ benefits. Over the long term, will there be an incentive to invest more conservatively? And there are no doubt many others I haven’t thought of.

None of that sounds like a great result even in the interests of spending less on tax concessions for people who clearly don’t need them.

One final point – both this government and the previous one have wittered about formally documenting a purpose for superannuation. In all my thinking about what our future state should look like, I’ve assumed that when someone eventually does that, the purpose will be in line with my particular paradigm (super is for saving for retirement but should result in money coming back out again during the member’s lifetime). No matter what the purpose ends up being, our next steps should be guided by it rather than just a knee jerk desire to take something from wealthy people.

Meg Heffron is the Managing Director of Heffron SMSF Solutions, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This is general information only and it does not constitute any recommendation or advice. It does not consider any personal circumstances and is based on an understanding of relevant rules and legislation at the time of writing.

To view Heffron's latest SMSF Trustee webinar, 'Super contributions unpacked', click here (requires name and email address to view). For more articles and papers from Heffron, please click here.