Paul Krugman, a professor of economics at Princeton University, famously pointed out a couple of decades ago, “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

Alas, productivity growth has been slowing in most countries. In the US and Australia, at least, the slowing began before the global financial crisis hit in 2008. Investors need to be aware of what’s happening to productivity and how this will affect future investment returns and the affordability of tax-payer funded pensions.

Productivity measures the ratio of the output of goods and services to the inputs of labour and capital that go into producing those goods and services.

There are two main measures of productivity. Labour productivity shows the output of goods and services per hour worked. Some part of the increases in the productivity of labour come about because of additions to the capital stock; when that’s been allowed for, we have what’s called multi-factor productivity or total-factor productivity. It shows the contribution to GDP growth from influences such as technical innovation, skills, competition, better management, increased scale, and the shift of labour and capital to more productive industries and firms.

The slowing in productivity growth

In Australia, productivity surged in the 1990s: labour productivity increased, on average, by 2.2% a year, and by 25% over the decade. That followed the big economic reforms of the Hawke-Keating government in the 1980s and our quick adoption of new information technologies (even though we were seen at the time as an ‘old economy’).

In the first decade of this century, labour productivity growth slowed to an annual average of 1.5%. In the financial year ending soon, growth in productivity looks likely to be about zero, even though there’s a boost in productivity in the resources sector as new mines are completed, existing ones are upgraded and production ramps up.

Australian governments have made few productivity-enhancing economic reforms in recent years, and the Rudd-Gillard changes to industrial relations reduced the flexibility of the labour market relative to the legacy of the Hawke-Keating years. And the easy-to-obtain gains for productivity from the revolution in information technology are now in place.

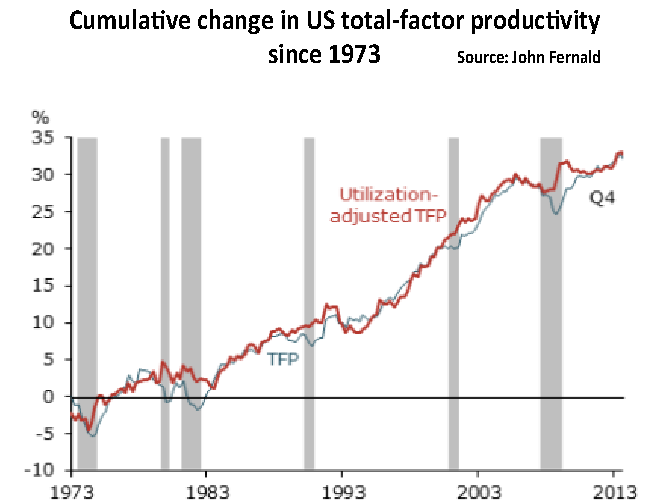

In other countries, too, productivity growth has slowed. John Fernald is a staffer in the US central bank and a guru on productivity. He points out that “the exceptional boost to (US) productivity growth from information technology in the late 1990s and early 2000s has vanished during the past decade. Although there is considerable uncertainty, a relatively slow pace is the best guess for the future.”

One of his graphs is reproduced below. The blue line shows the cumulative growth in total-factor productivity in the US since 1973 and the red line shows this adjusted for the capacity utilisation rate, to eliminate the effects on productivity from cyclical swings in the US economy including from the financial crisis. The US productivity slowdown began almost two years before the US went into recession.

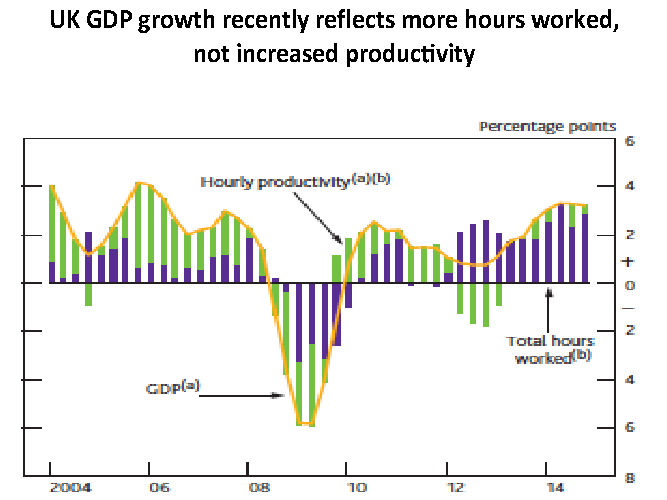

The Bank of England recently reported that, “Despite robust output growth in the past few years, productivity growth has remained subdued with the increases in output having been met mainly through an increase in total hours worked”.

The impact of a slowdown in productivity growth

Below-par growth in productivity, if it continues, will be bad news for the economy and will hurt investors. The rates of increase in average real wages and in profits would be constrained. Governments would find it even harder to generate the tax receipts to pay for the future costs of ageing populations (the Intergenerational Report assumes, heroically in my view, that productivity growth will average 1.5% a year for the next 40 years).

Also, a slowing in productivity growth raises the risks of inflation. Perversely, slowing growth in productivity does help job creation in the short term. Currently, each of the US, UK and Australia is creating more jobs for every percentage point increase in GDP than if productivity growth were stronger.

The dissenters’ views

There are respected economists and investment strategists (including Martin Feldstein who chaired the US Council of Economic Advisers under Ron Reagan, and Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs) who point to the difficulties of measuring productivity. They argue that the much-vaunted weakness in productivity growth is a statistical myth.

In their view, the usual measures of productivity growth prepared by government statisticians understate growth in GDP (and in productivity) and fail to incorporate the dramatic gains in the quality of products and services, particularly the use of software and digital content.

Professor Feldstein writes: “…consider the higher price of a day of hospital care. How much of that higher price reflects improved diagnosis and more effective treatment? And what about valuing all the improved electronic forms of communication and entertainment that fill the daily lives of most people? In short, there is no way to know how much of each measured price increase reflects quality improvements and how much is pure price increase.”

In Mr Hatzius’ view, rapid technological change means that productivity growth is being underestimated by “a meaningful amount” – thus there’s even less inflation than official figures show. He concludes that “if true inflation is even lower than measured inflation – and especially if this gap is bigger than it has been historically – the case for keeping (US) monetary policy accommodative strengthens further.”

A balanced assessment

It’s all very well to acknowledge the big effects on the quality and content of many of the products and services available to us that result from rapidly changing technology. But when it comes to what most people see as their real incomes, or to measuring inflation, or to considering the extent to which there’s slack in the overall economy, we need to be cautious in how much additional ‘value’ is put on the never-ending developments in or from technology.

And in long-term projections, such as the 40 years ahead considered by the Intergenerational Report, an assumption of average growth of 1.5% a year seems far too optimistic.

An understanding of what’s happening to productivity will be of special importance to central banks in coming years as they seek to set monetary policy accurately according to ‘true’ economic conditions.

Don Stammer chairs QV Equities, is a director of IPE and is an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund and Altius Asset Management. The views expressed are his alone. An earlier version of this paper was published in The Australian.