Some of the best movies have an ensemble, where each actor brings their unique skills to make the story work. Likewise, with a sports team, a single player cannot always lift a whole team to glory. In both of these instances, an idea to achieve the outcome gestates until either success, mediocrity or failure occur.

The same is true in funds management

Last month, the LA Rams won the 2022 Super Bowl. Coach Sean McVeigh built a team with a deep bench of superstars. Wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr went down with an injury in the second quarter but he was one of many skilful catchers in the Rams line-up. Any one of a dozen players could have been MVP in the big game. By building a team with a deep bench, McVeigh reduced his key person risk.

Other teams in the NFL rely on a franchise player, usually the quarterback. This person becomes the face of the franchise. The risk, of course, is if that one player is injured or has a run of bad form the team suffers more.

In sports, talent costs money. The same is true in funds management, hence the willingness of investors to pay premiums of active management. With active management, investors pay for the expertise of the star fund manager and/or the deep bench of analysts. The industry is rife with fund managers and investment gurus that live and breathe markets. Some genuinely have talent identifying opportunities while for others the self-belief is misplaced and they were just lucky, in the right place at the right time.

The difficulty for investors is determining if their active fund is managed by a deep bench of stars that are skilful, not lucky. This is easier said than done, as many fund managers are not transparent. It is difficult to get a complete list of holdings to determine how they are outperforming.

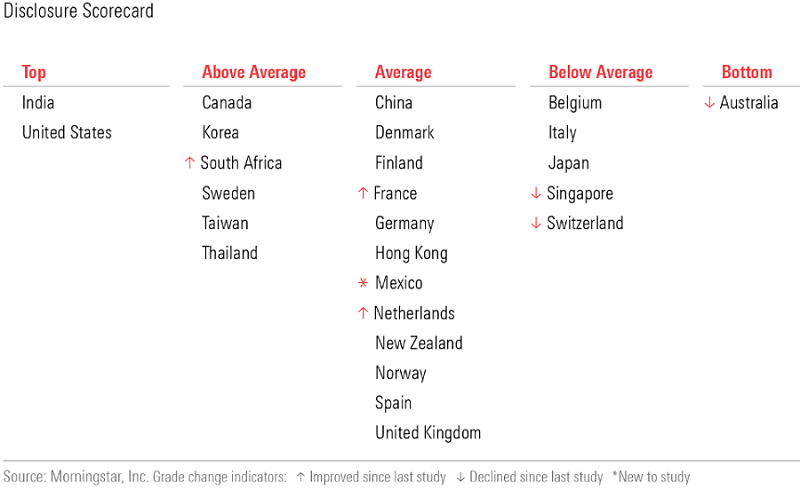

Global research house Morningstar in its biennial Global Investor Experience Report repeatedly ranks Australia last out of 26 global markets in terms of investment disclosure.

Ideally, investors should be able to assess performance over a long period. They should be able to look at the holdings and determine whether a fund outperformed because its managers were skilled at choosing the best securities, or were they just more heavily weighted into growth assets or those asset classes that have done best over recent periods?

Performance should come from multiple sources, across sectors, not just a single idea. In addition, outcomes should be persistent and consistent with stated expectations and marketing.

If a fund manager says their skill is identifying ‘value’, investors should expect when value shines, as it is now, so should they. Likewise, when a manager says they specialise in identifying ‘quality’ companies, expect they would fall less and recover faster during a downturn, as that is a key characteristic of quality.

It would be naïve to think any manager can outperform every month. Fund managers are human after all, so they will make mistakes. In investing, mistakes include selling too soon, holding a stock for too long and overlooking opportunities. Making mistakes can make some fund managers better investors but mistakes can lead to underperformance. As humans, they may become impatient and try to chase returns, or hold that stock they’ve fallen in love with, a stock which is cheap for a reason. Investors are human too, so persistent underperformance may lead to a run for the exit.

What is an investor to do?

There is of course a way to eliminate key person risk: passive management. It aims to replicate the returns of an index as opposed to active management that aims to outperform an index.

The days of outperforming the market are not gone. Investors that still want to achieve an outcome different from the market benchmark index and to take the ‘human element’ out of their portfolios could turn to smart beta ETFs.

Smart beta is at the intersection of active and passive management. It can explain a considerable portion of an active manager’s risk and return characteristics but it is not subservient to the human condition and our vulnerabilities. It does not ‘fall-in-love’ with stocks, is not impacted by what else is going on in its life and it does not retire or resign to work for a competitor. But there is a human behind the research and design of smart beta indices, and over the last 50 years, it has become more sophisticated. Smart beta ETF strategies are fully transparent so investors can see the holdings on a daily basis.

Forewarning the rise of smart beta was a 2016 scholarly article published in the CFA Institute's Financial Analysts Journal. In their paper, ‘The Asset Manager's Dilemma: How Smart Beta is Disrupting the Investment Management Industry', authors Ronald Kahn and Michael Lemmon described smart beta as:

“a disruptive financial innovation with the potential to significantly affect the business of traditional active management.”

Their paper illustrated that current fee levels in the global equity universe were inconsistent with the performance outcome because the fees are too high. Over 35% of global equity managers, according to Kahn and Lemmon’s analysis, will be disrupted by smart beta.

The disruption is happening in Australia

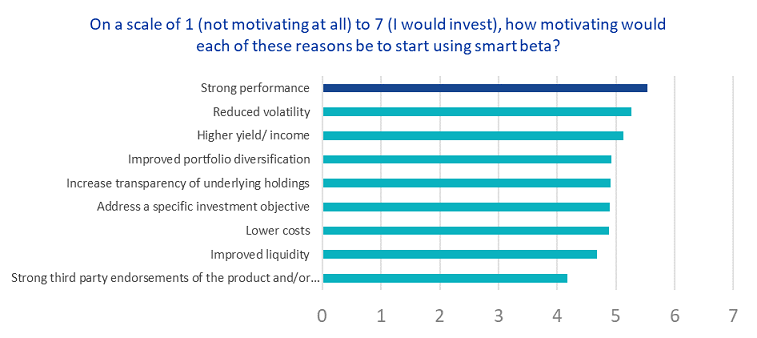

Each year VanEck conducts a smart beta survey. Last year, the Sixth Annual Smart Beta Survey was the biggest survey of its kind worldwide.

A question directed at financial advisers demonstrated that the most important factor for an adviser selecting smart beta is not fees but performance.

Source: VanEck Smart Beta Survey, 2021

Active managers should take note. Each half year when S&P releases its SPIVA report for Australian funds it does not make good reading for active fund managers. During the most recent (half year 2021), the summary states:

“For longer measured periods (3, 5, 10, and 15 years), the majority of active funds underperformed their respective benchmark indices across categories.”

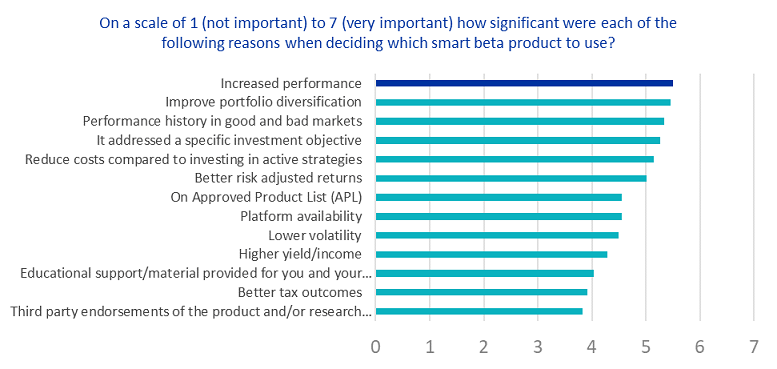

More worrying for active managers, the VanEck Smart Beta Survey indicates over 50% of advisers are using smart beta to replace active managers. The main reason is increased performance.

Source: VanEck Smart Beta Survey, 2021

The survey also found 99% of smart beta users are satisfied with their strategy. This finding has been consistent in every year of the survey.

No fund manager, and for that matter, no index strategy will offer absolute returns all of the time. Investing involves risks. Key person risk is one such risk. Prudent investing means not just diversifying your bench across asset classes but also across investment styles.

The key for investors is to diversify and seek those strategies that endure through the cycle and the complex gauntlet that capital markets exhibit time and time again. It is common now to see smart beta as the core of a portfolio supported by high conviction active funds, or to see a core active manager blended with a complimentary smart beta strategy.

For more information on smart beta, click here.

Arian Neiron is CEO and Managing Director - Asia Pacific at VanEck, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This is general information only and does not take into account any person’s financial objectives, situation or needs.

For more articles and papers from VanEck, click here. VanEck's smart beta funds include an equal-weighted Australian equity fund (ASX:MVW) and global quality (ASX:QUAL).