[Editor's note: The words in Jeremy's heading and their abbreviation, CIPR (pronounced 'sipper'), come from the Financial System Inquiry and they are quickly becoming part of the superannuation industry lexicon. We need another word or abbreviation. Such a clunky set of letters will do nothing to encourage engagement with post-retirement products. Suggestions welcome.]

The retirement income stream market in Australia is unusual by global standards, being dominated by the ‘balanced’ account-based pension (ABP). It has usually been recommended to investors on the basis of underlying investment choice, flexibility, control and liquidity.

As observed by the Financial System Inquiry (FSI) in its final report, and made clear by their impairment during the GFC and in its aftermath, the average ‘balanced’ ABP can’t adequately manage the unique risks of retirement. It should be viewed as part of any retirement portfolio, rather than the entire solution.

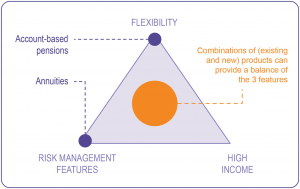

So it makes sense that the FSI recommended that all large APRA-regulated super funds ‘pre-select’ a comprehensive income product for retirement (CIPR) that addresses the need for retirees to have:

- high income

- risk management features

- flexibility

The FSI believed that this requirement is likely to be satisfied by using a combination of products, starting with the ABP. This was illustrated in the FSI’s final report as follows:

Desired features of retirement income products

The final report suggested the potential for a wide range of CIPRs which, in addition to the existing ABPs and annuity products, included combinations with:

- deferred lifetime annuities (a product commonly used overseas, but not yet here)

- group self-annuitisation schemes (GSAs) (a new concept)

- deferred GSAs and

- other future innovations.

Making the comprehensive income product more understandable

One challenge faced by the broad, non-prescriptive CIPR concept is that any product or portfolio will have to be easily understood and evaluated by fund members. To provide guidance, minimise subjectivity and promote more consistency of retiree outcomes, we might wish to consider the use of a balanced scorecard approach. The scorecard would assign a qualitative rating to each strategy or feature addressing the three CIPR requirements.

The scorecard could be developed by APRA using its standards-making power under broad principles that could be set out in the SIS Act. This process would allow for appropriate consultation with the industry. Designing the scorecard would, however, involve making some qualitative decisions about the differences between certain retirement income strategies. For example, a core principle should be that an investment strategy or asset allocation alone does not satisfactorily deal with longevity risk. Higher expected returns should be a positive, but income volatility should lower the rating. Similarly, CIPRs that did not have an express inflation management strategy or a means for combating sequencing risk would also get lower scores under the balanced scorecard idea.

Using a scorecard would enable easy comparison for retiring fund members and their advisers, and provide some regulatory guidance, without reducing the ability of fund trustees to tailor their offer to the specific needs of their own members (eg taking into account different demographic factors and the like). The balanced scorecard would essentially operate as a ‘nudge’, using a transparent rating system to influence the behaviour of product providers and retirees alike.

Recognise every retirement is different

To take our retirement income system to the next stage of its evolution, the CIPR concept must be impactful, while at the same time allowing tailoring, innovation and the accommodation of different demographics, account balances and so on. After all, every retirement will be different.

It also needs to be palatable. Given that workers are already forced to save some of their own wages through compulsory superannuation contributions, further compulsion is unwarranted. Murray has highlighted though, that the system is letting retirees down in leaving them exposed to risks that they cannot manage on their own.

Disclosure of the ratings to consumers in a meaningful way could be key to the success of the concept. Getting the disclosure right will involve attention to other global examples and, ultimately, consumer testing. Something similar to the ENERGY STAR® ratings used for new electrical appliances in Australia might be a start. Ideally, the rating system would be something that consumers will understand and trust.

If done properly, it should be possible for the scorecard to highlight trade-offs between risk management, flexibility and returns. If retirees, as consumers, come to understand that they cannot have the highest income with full flexibility and be protected from every risk, then advisers and funds can have a discussion about the mix that they provide.

The scorecard is likely to be both informative and slightly normative in effect. Funds and product makers are likely to respond to the incentive to seek higher, rather than lower, ratings. A low-scoring CIPR would still be compliant and there would be nothing preventing retirees from investing in it. Retirees might be advised to opt for a low-scoring CIPR because they have, for example, substantial assets, an expected inheritance or a longevity product in another structure. Similarly, the scorecard would not supplant advice and is really a ‘labelling’ idea. It would necessarily be only part of the process of determining the appropriate retirement strategy for a retiree. There is no silver bullet solution in retirement.

More choice for retiring members

There is only upside in introducing CIPRs. A CIPR simply provides more choice for retiring members. Super funds will be free to retain their existing range of retirement options and to introduce new products alongside CIPRs. Retirees would have no obligation to participate in a CIPR. In every way a CIPR would be a ‘choice’ product, especially when compared with MySuper. Whereas MySuper requires a young, typically less-interested worker to do nothing or opt-out, a ‘nudged’ CIPR requires a mature, engaged retiree to opt-in. This is a key point.

It is a well-recognised feature of pension systems around the world that a retirement solution put forward by the fund itself carries with it an implicit recommendation that it is appropriate. This, again, positions the CIPR as a useful policy initiative. Fund trustees will be aware of the duty of care involved. The underlying policy purpose of the CIPR concept is to provide better risk management for retirees than is currently being afforded to them.

The retirement phase is the remaining aspect of super that needs to be brought into the 21st century. If the idea of some sort of qualitative filter or signal, such as the balanced scorecard, is embraced by the industry, then the CIPR might just be the springboard for super to become recognised as the world’s leading retirement income system.

Jeremy Cooper is Chairman, Retirement Income at Challenger Limited, former Chairman of the Super System Review (the Cooper Review) and Deputy Chairman of ASIC from 2004 to 2009.